This article was published in partnership with Local Call.

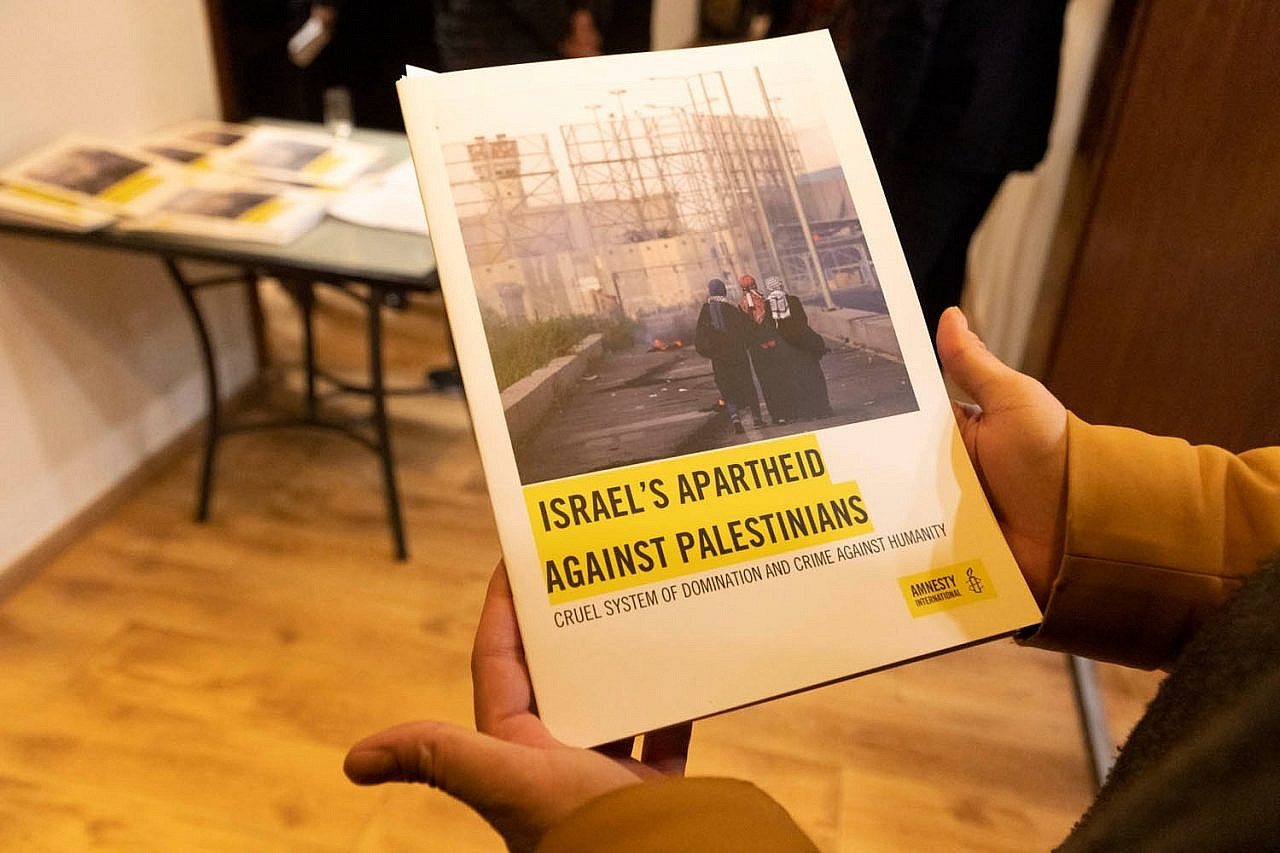

Over the last year and a half, international and Israeli human rights groups have published several deeply–researched reports concluding that the Israeli regime from the river to the sea amounts to a system of apartheid based on Jewish supremacy — which Palestinian groups and others have long argued.

These reports, of course, provoked severe backlash from Israeli leaders, who rushed to label them antisemitic. But criticism of the reports was also heard from segments of the Israeli left which see apartheid as restricted to the occupied West Bank alone, where Israel has built separate legal systems for settlers and Palestinians. In Israel itself, they argue, the situation is fundamentally different.

According to them, while Israel enacts discriminatory and often racist policies against Palestinian citizens, that is not fundamentally different from the way other nation-states discriminate against minority groups. This position is reflected, for example, in a report published by Israeli human rights group Yesh Din last year, which enumerated the manifold ways in which the crime of apartheid is carried out strictly beyond the Green Line.

Almost ironically, it seems that official Israel is the one that has finally resolved the dispute between these two approaches in recent weeks, with the dissolution of the government and the start of a fifth election cycle in less than four years.

In his decision to dissolve the government in order to save its apartheid policies in the occupied territories, Naftali Bennett clearly illustrated both that Israel’s apartheid regime stretches across either side of the Green Line, and that the logic of Jewish supremacy is the foundation upon which this regime was built. In other words, “Jewish and democratic” Israel is fully enslaved to the maintenance of apartheid: this is the government’s paramount goal, overriding any other consideration related to the interests of the citizens living within the sovereign borders of the state.

But there is also another way that the political farce in which we currently find ourselves undermines the position that apartheid is limited to only one part of this land. Adherents of this position consistently point both to the status of Palestinians citizens of Israel and the fact that the last year saw an Arab party join the government as proof of real political partnership between Jews and Arabs that nullifies the apartheid claim, at least inside the Green Line.

But rather than wonder whether this so-called partnership succeeded, it would be prudent to ask ourselves how we understand the term, and whether real partnership is possible in a supremacist regime.

What does partnership mean?

Partnership, in its most basic sense, is the ability of all parties at the table to take equal part in setting the rules of the game. This is something the Zionist regime has never once offered to its Arab citizens — not even to the Ra’am party in Bennett’s coalition, which rather was given the possibility of obtaining some basic, self-evident rights for their constituents.

Palestinians with Israeli citizenship begin from an inherently inferior political, economic, and social position, and it is from this position that they bargain for their civil rights in return for renouncing their national identity, their struggle against the oppression of their people, and any aspiration for justice and true liberation. This is not partnership — at best it is political blackmail.

On the other hand, the Arab public in Israel has extended a long-standing invitation to Israeli Jews for real partnership in the form of a state of all citizens, which has repeatedly been received with indifference and disregard at best, and labeled as extreme and dangerous at worst.

The vision of a state for all citizens, which was put forth by the Balad party in the 90s, is a brave invitation for true partnership in which both Israeli Jews and Palestinians have their individual and collective rights recognized and have an equal opportunity to mold the identity of this country. Joint List leader Ayman Odeh, who hails from the socialist Hadash party, also offers the Jewish public a real form of partnership. But like Balad, Odeh was denounced as an extremist and a traitor as soon as the Jewish public realized that he had no intention of relinquishing his identity as a Palestinian, or accept the rules of the game, according to which he must remain silent as the regime oppresses his people on both sides of the Green Line.

The four vision documents published by leading bodies of Palestinian civil society in Israel between 2006-2007 were another clear call for a partnership that demanded Arab citizens have the right to take part in formulating the rules of the game in their homeland, rather than haggling over the crumbs. It is difficult to overstate the importance of these documents, which could have formed the basis for a different, egalitarian, and democratic dialogue between Arab and Jewish citizens in the country. Unsurprisingly, like Balad and Ayman Odeh’s proposals, they were met with almost complete public indifference by the Jewish public and their political representatives.

Today, every single Israeli citizen, on both the right and the left, understands the depth of the collapse of the Israeli political system. In order to uproot this pathological rot, we must first recognize that between the river and the sea is a single apartheid regime, one that originated from, and continues to be propped up by, the lie of a “Jewish and democratic” state within the Green Line. Within these borders, Israel has only offered its Palestinian citizens bargaining power over the degree of their oppression.

A version of this article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.