Outside Romania, the tyrannical reign of Nicolae Ceausescu from 1965 to 1989 is mostly remembered for how it ended — with the execution of the dictator and his wife, Elena. Less well-known, however, is the fact that Ceausescu was a “friend” of Israel for many years. In fact, Romania at the time was alone among the Eastern European communist regimes in maintaining diplomatic ties with the Jewish state.

Recently-opened files from the Israel State Archives that belonged to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs complicate this picture, however. According to numerous documents, officials at the ministry believed that Ceausescu’s positive disposition toward Israel was rooted in anti-Semitism. A March 30, 1967 telegram sent by the Israeli ambassador in Bucharest states that Ceausescu “saw Israel as a center for rich Jews whose economic abilities and international connections could be of use, including American Jews.”

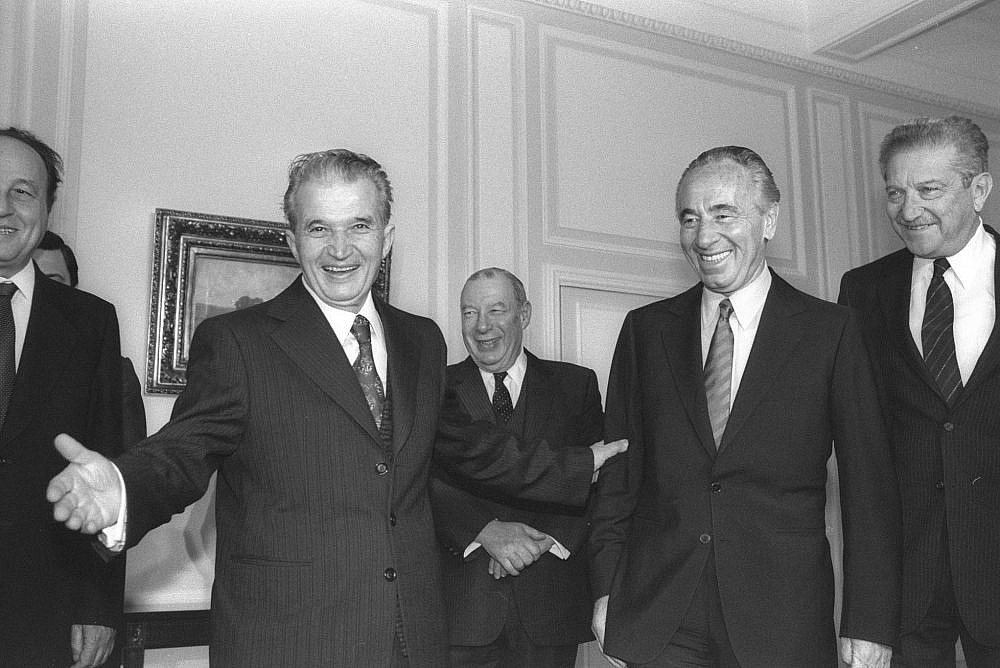

Yet Israel’s own assessment that Ceausescu’s overtures were driven by anti-Semitism did not stop the government from establishing positive ties with his regime, including official visits by several Israeli prime ministers in the 1970s and 1980s.

The Foreign Ministry documents also reveal that Israel was aware of the domestic suffering caused by Ceausescu’s rule, with Romania’s starving citizens repressed and terrorized by his government. Some documents discuss how those suspected of criticizing Ceausescu were hospitalized in psychiatric institutions for extended periods, while those suspected of wanting to emigrate or protest their conditions of employment were fired, barred from working elsewhere, and left destitute. The communist party elite and the upper echelons of the security services enjoyed better living conditions, while the low wages of laborers in the industrial sector were periodically docked whenever there was a shortage of raw materials and production slowed down.

Every Romanian citizen was expected to take part in the Ceausescu personality cult in order to avoid interrogation rooms, forced labor, or social ostracization. Entire villages were razed and their inhabitants moved into mass housing in order to facilitate surveillance — even at the cost of agricultural production and increased famine. People paid for pensioners to stand in line and buy food on their behalf because shop shelves would be empty by the end of the work day.

The secret police were also everywhere. Ceausescu personally appointed heads of security, judges, and prosecutors. Despite the ban on a political opposition, “elections” to Romania’s congress were held in which over 98 percent of voters chose Ceausescu. Yohanan Cohen, Israel’s ambassador to Romania from 1973-1976, wrote that he had never seen “a more mocking and distorted expression of the idea of democracy.”

Embracing Israel because of anti-Semitism

Diplomatic ties between Israel and Romania were established shortly after Israel’s creation in 1948. Until the end of the 1950s, the relationship was restricted to limited trade, and the Romanian government granted the occasional request from its Jewish citizens to emigrate to Israel.

Relations between the two countries began to warm from 1965, when Ceausescu took over and Romania abstained from a series of anti-Israel votes at the UN General Assembly. Following the Six-Day War in 1967, when other Eastern European communist regimes cut ties with Israel, Ceausescu’s Romania remained the only such country to maintain full diplomatic relations. Trade between the two states grew, and Romania imported oil through the Trans-Israel pipeline. In 1972, Prime Minister Golda Meir traveled to Romania on an official visit.

One could reasonably assume that Ceausescu’s readiness to establish ties with Israel, despite pressure from Moscow and Arab countries, stemmed from his wish to maintain an independent foreign policy in the face of ever-present tensions between him and the Soviet Union, and his fear that Moscow was working to topple him. But – as the archives mentioned above show – Israeli diplomats at the time begged to differ.

According to their assessment, Ceausescu believed that Israel and Jewish financiers controlled the world, including the U.S., and wanted, through them, to persuade Washington to make Romania the exception to its limited ties with communist countries. This, Ceausescu hoped, would allow him to implement his economic plan for Romania.

A telegram from the Israeli embassy in Washington, dated April 5, 1967, notes that “the Romanians have developed a vision of Israel’s trading abilities as the international center of the Elders of Zion. They sincerely hope that we will help them with their exports to the United States… which is currently off-limits to them.”

Israeli officials did not try to dispel these anti-Semitic notions, and instead continued cooperating with Romania. A letter from the Israeli ambassador in Bucharest, dated Oct. 9, 1967, states that “the Romanians are especially interested in growing their exports to the U.S… They are relying on our help in this area. I understand that we have promised to make an effort in this regard and have done so, without much success.”

Another telegram, dated Feb. 15, 1968 and sent by the Israeli ambassador in Tehran while Romania and Iran were in discussions over the former importing oil via the Trans-Israel pipeline, notes that the Romanian ambassador believed that Israel could win support “from Jewish Rothschilds in the U.S.” In June 1976, Cohen wrote that Romania’s relationship with Israel was driven by “belief in the power and influence of world Jewry, particularly in the U.S.”

Most Romanian Jews continued to be prevented from leaving, despite growing trade between the two countries and Ceausescu’s support of Israel at the UN. Occasionally, the regime would demand a steep “fine” from some of those requesting a permit to emigrate to Israel — a sum that they did not have. As part of this extortion, certain Jews who wished to leave were arrested under false pretenses and forced to pay the “fine” as a condition of their release.

Israeli officials believed anti-Semitism was driving these efforts to extort Romanian Jews. A March 17, 1970 telegram from the Israeli ambassador in Bucharest noted an increase in the number of workers fired after submitting requests to leave Romania for Israel. The ambassador stated that this was an attempt by the Romanian regime to pressure Israel as part of its “innate anti-Semitic impulse that finds an outlet here and there.”

In another telegram, sent April 29, 1970, the ambassador wrote that Ceausescu’s interest in impeding Jewish emigration stemmed from his government’s negotiations with West Germany, regarding compensation for Nazi persecution in Romania. The sum involved depended on the number of Holocaust survivors in the country – hence Ceausescu’s desire to prevent Jews from leaving.

Growing numbers of Jews were eventually allowed to emigrate in the mid-to-late 1970s. According to a summary of relations between the two countries from 1974 to 1977, a leading cause of this shift was “the desire to open a Jewish ‘nature reserve’ in Romania, and with that to prove to the U.S. the country’s tolerance and liberalism (in contrast to other Eastern European countries).” Another factor was “the tendency to protect Jews as an economic resource whose value did not diminish over time.”

In the mid-1970s, the Ceausescu regime began supporting the establishment of an independent Palestinian state, and began publicly criticizing Israeli policy in the occupied Palestinian, Egyptian, and Syrian territories. This change in policy was uncomfortable for Israeli diplomats, but they declined to react so long as the countries’ official ties remained normal.

It’s worth noting that Israel’s restraint in this regard was markedly different from its fierce response when it suspected Latin American countries of developing ties with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and Arab states. By contrast, Israel refrained from criticizing meetings between Ceausescu and Arab leaders, and did not stir a diplomatic crisis when he met with Yasser Arafat, head of the PLO, in 1979. There was also no protest from Israel when the PLO opened an office in Bucharest in the 1970s.

‘Yes, but you’re a Jew’

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the repeated failures of Ceausescu’s economic policies were coming to light, and trade between Romania and the U.S. had failed to materialize. There were also rumors of growing dissatisfaction among the upper ranks of the Romanian government and security services.

At the same time, reports reached Israel that the Ceausescu regime was blaming its failures on Israel and world Jewry sabotaging relations between Bucharest and Washington. This rhetoric sparked a wave of anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial in Romania. Forbidden by law from publishing anything that contradicted the official regime line, Israeli diplomats concluded that the dam of anti-Semitism had burst.

A telegram from the Israeli ambassador in Bucharest, dated May 19, 1980, refers to a survey of Holocaust victims conducted by a Romanian newspaper, from which Jewish victims were omitted. In another telegram, dated Oct. 22, 1980, the ambassador mentions an anti-Semitic article published by a magazine of the Bucharest municipality.

A Dec. 12, 1980 telegram from the ambassador describes a Romanian Writers Association ceremony in which a literary translation prize was awarded to a Jewish translator. The presenter of the prize expressed his amazement at the translator’s command of Romanian, and when she asked him why, given that Romanian was her mother tongue, he replied, “Yes, but you’re a Jew.” Later on, drunk, the presenter told her that every Romanian is an anti-Semite, and that he himself was no lover of Jews.

A television program about World War II and its victims was the subject of an April 6, 1981 telegram from the Israeli ambassador. The program featured pictures of Janusz Korczak, Anne Frank, and the Warsaw Ghetto, along with Jewish women on their way to the gas chambers, while omitting to mention anti-Semitism or Jews, so as to give the impression that the only victims of the Holocaust — including those in the photos — were Romanians or other (non-Jewish) groups. Another telegram from a few weeks later describes an English-Romanian dictionary in which “Jew” is defined as a money-changer and extortionist.

On Oct. 4, 1981, a telegram notes that the Austrian, U.S., and Italian ambassadors had alerted the Israeli ambassador to speeches by Ceausescu and other Romanian officials condemning “cosmopolitanism.” The understanding was that they were making anti-Semitic references to Jews. Israeli foreign officials believed anti-Semitism to be taking root anew in Romania, due to the remnants of extremist, anti-Semitic, and neo-Nazi groups such as the Iron Guard — whose members Ceausescu was in the process of exonerating, offering them rehabilitation and a place in public life.

None of this prompted Israel to rethink its positive relations with the Ceausescu regime. Just as it maintained ties with five military dictatorships in Latin America and Africa during the same period, in exchange for support in international forums, Israel seemingly acquiesced to Romania’s anti-Semitism and its holding of Jewish citizens hostage. In his 1976 communique, Cohen wrote that “establishing normal and multi-faceted ties between Romania and Israel is rightly seen by us as a national asset. At a time when dozens of countries have severed ties with Israel, and our international standing is being undermined, this is particularly noteworthy.”

Israel therefore decided to protect its diplomatic ties with Romania at any cost, believing that any public crisis or recalling of ambassadors would be a victory for the Palestinians and the Arab states. That price included accommodating Romania’s open anti-Semitism, and preventing Holocaust survivors and their descendants from emigrating to Israel.

This article was originally published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.