Muhammad, a young queer Palestinian, was forced to flee the West Bank when his life was under threat over his sexual identity. “I’d heard Israel was the most LGBTQ friendly country in the world, especially Tel Aviv,” he recalled. “I would read and watch videos. It all looked good on the screen.”

Reality, however, proved to be very different. “If I had known what it was really like, I would have rather died in the West Bank than live here like this,” he lamented.

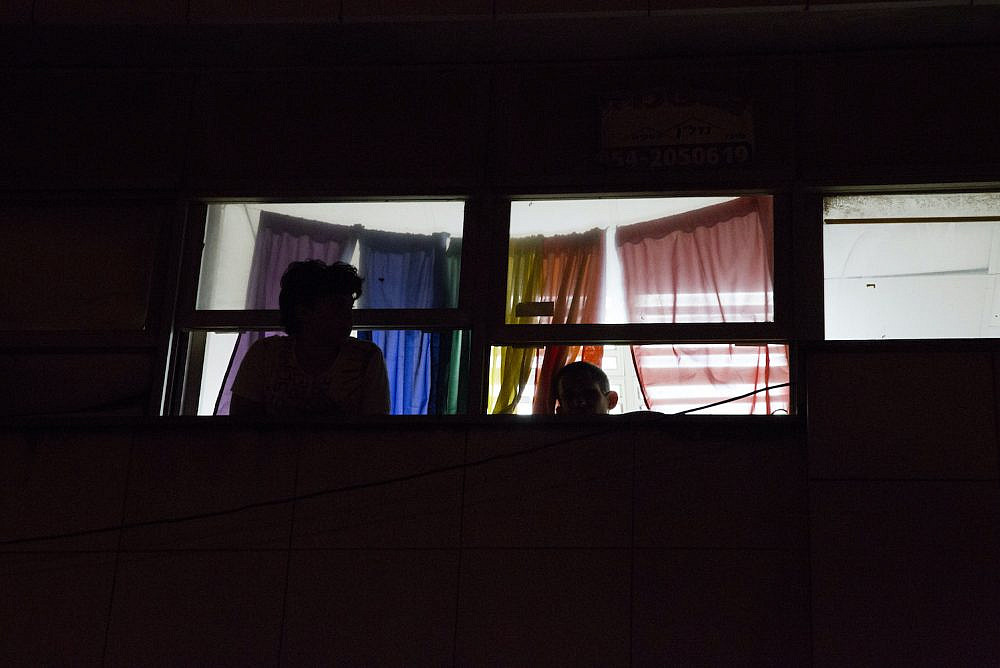

Muhammad is not alone. At least 60 queer Palestinians have had to flee the West Bank in fear for their lives, and have come to Israel hoping to find some safety. But while the state that markets itself as an “LGBTQ paradise” knows these individuals are here, it carries out very abusive policies toward them. Their stories, shared here under pseudonyms to ensure their safety, can only be described as Kafkaesque. They starkly expose how Israel, a purported haven for queer Palestinians, is, in fact, a hellish reality for them.

Israeli abuse of at-risk LGBTQ Palestinians takes many forms. They are generally met with institutional hostility marked by disregard for the mortal danger they face; subjected to police brutality; put through unending red tape; and confronted with myriad barriers that require legal assistance for the most trivial matters, with many unaware of how to access such legal aid.

At-risk LGBTQ Palestinians especially suffer from financial abuse. They are eligible for temporary “stay” permits that are valid for only a few months, and which do not include a work permit. This limited status exists despite the fact Israeli law and jurisprudence recognize asylum seekers’ right to live in dignity, and is further enshrined in international conventions signed by Israel. Without access to legal employment, they are often forced to live in poverty while relying on “under-the-table” jobs.

To make matters worse, these Palestinians are routinely excluded from programs that are meant to secure basic healthcare for other asylum seekers in Israel, another fundamental right guaranteed by Israeli and international law. Their access to basic social rights such as shelter is also blocked, with many reporting they have had to sleep on the streets, spend nights in unfamiliar places with strangers, and have been exposed to danger and exploitation.

Ahmad, a young gay man, experienced many of these hardships when he fled to Israel after facing violence and threats of murder from men in his family who discovered his sexual orientation: “I was sick, and I couldn’t go to the hospital. My body and my teeth hurt. I couldn’t sleep or eat for several days. I couldn’t rent an apartment. I couldn’t work legal jobs. I worked under the table. Yes, I did have permits, but you’re not allowed to do anything.”

Another young man, Muhammad, says, “Do you understand that I’ve been trying to open a bank account since last August and still haven’t been able to? Even if I do manage to open an account, I won’t be able to get cheques. I want to rent an apartment, and you need cheques for that, so I must have roommates. I work under the table — no pay stub, no nothing. I have no rights here at all.”

Muhammad continues, “If I want medical treatment, there’s the human rights clinic [run by Physicians for Human Rights-Israel]. I have no medical insurance. The only thing the system will give me is stay permits, which expire every six months. When the next one expires, I’ll wait for a month again before I get a new one… I can’t get a driver’s license… I can’t even get a Rav Kav [public transportation pass] with a photo. I want a monthly pass, but I can only get a daily or weekly pass.

“These are the little details that make life harder and harder,” he says. “Everything is impossible.”

The fewer Arabs, the better

Although Israel does not recognize at-risk Palestinians as asylum seekers, it is bound by the fundamental international principle of “non-refoulement,” meaning a person cannot be returned to their place of origin so long as their life or liberty is in danger there; this obligation has also been validated by Israel’s Supreme Court.

Israel is doing everything in its power to reduce its obligations to at-risk Palestinian refugees and limit its duties to non-refoulement only. For example, Israel claims it does not have to admit at-risk Palestinians since it considers all Palestinian refugees to be under the care of the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) — the organization dedicated specifically to Palestinian refugees since 1949 — and therefore are excluded from the protections afforded to other peoples under the UN Refugee Convention.

In practice, according to UNRWA’s establishing guidelines, Palestinians who were not uprooted from their homes in the wars of 1948 or 1967 are not entitled to the agency’s assistance. About a quarter of the Palestinian population of the occupied territories are recognized as refugees by UNRWA.

Trapped between Israel’s commitment to non-refoulement and its staunch rejection of any Refugee Convention obligations for Palestinians, LGBTQ persons who have crossed the Green Line have found themselves in a catch-22 that reduces their lives to a daily struggle for survival.

The current system under which at-risk Palestinian LGBTQ persons remain in Israel is fairly new. It is the product of multiple petitions filed on behalf of individuals in need of asylum, which ultimately resulted in the court pushing the state to appoint a government committee to regulate the matter. In its concluding report, released in 2014, the committee flatly denied systemic persecution of Palestinian LGBTQ persons in the occupied territories, and claimed that they come to Israel “to enjoy the more liberal way of life.”

Nevertheless, as part of Israel’s recognition of non-refoulement, the committee placed the responsibility for the matter with the welfare coordinator for the Civil Administration — the Israeli military body that governs civilian affairs in the occupied territories. Since then, the welfare coordinator has had the authority to grant exceptional stay permits to individuals facing a genuine threat. Absurdly, the very same report that gave this power to the welfare coordinator — a social worker by training — states the person holding this position lacks the training and tools to assess such cases.

The permits granted by the welfare coordinator do not allow at-risk refugees to work, nor do they give them access to health insurance or social services, and they involve further bureaucratic and legal complications. The permits are valid for three to four months, forever keeping holders “on edge.”

In addition, as a prerequisite for renewing their permit, applicants are required to apply for resettlement in a third country, a process that can take years. Resettlement in a third country is reserved for situations in which the initial country of refuge cannot take in refugees due to lack of resources. The number of at-risk persons seeking asylum in Israel is hardly a burden on state resources. It seems that the insistence on resettlement as a condition for stay permit renewal is rooted in a simple ideological motivation — the fewer Arabs in the country, the better.

“It’s truly evil, because these are people who have nothing to eat,” says Merav Ben Zeev, a lawyer with HIAS, an American Jewish organization that works to protect refugee and migrant rights, and which published an extensive report in 2019 on the predicament of Palestinian LGBTQ asylum seekers in Israel. “It makes no difference if they renew for three months, six months or two days — a person needs to eat, and if they can’t work, how are they supposed to eat?”

Ben Zeev says that these restrictions, and the fact that these refugees cannot access the rehabilitation they need, forces many of them to survive through prostitution, which can often lead to drug use. “Our fear is that a criminal case will be opened, meaning resettlement won’t be approved, and the person would then remain in limbo in Israel,” she explains.

Fearing family members, extortion attempts

Ahmad, who received refugee status, now lives, works, and studies abroad. He speaks of a good childhood before leaving the West Bank and Israel; he was the youngest brother and received a lot of warmth from his family. “When I went to school at age six, I started looking at kids who were older than me,” he says. “I felt these emotions, and I didn’t understand what it was… but I was embarrassed, and I looked at them from a distance.” Ahmad recounts how he came home and naively said he wanted to marry one of the boys. His family responded with warnings about religious prohibitions and punishments in hell.

As a child and as a teen, Ahmad was celebrated for his dancing abilities; but as he grew older, people around him started pulling away, and his family tried to teach him to be more like other boys around him. As he went through his process of self-exploration, he also tried to talk and behave like the rest of the boys at school. But, despite these attempts, “at that time, I really looked like a girl, the way I talked, the way I sat, drank, everything. I was 17, and you could tell I was gay.”

Ahmad talks about how he developed an alternate social life on social media using fake profiles, and even had a few secret sexual encounters. That was how he first went to Tel Aviv and saw LGBTQ people living without having to hide, which he had found so difficult.

After moving to a different city in the West Bank, he was able to gain some independence and freedom. But he then met someone on social media who tricked him into sending a photo showing his face. After an attempt at blackmail which Ahmad rebuffed, the blackmailer exposed him, posting his name and photo.

Before his family got wind of the news, another person tried to blackmail Ahmad by threatening to out him directly to his father if he refused to sleep with him. “That guy contacted me and started sending me messages: ‘If you don’t sleep with me, I’ll tell your father, and we know your father; he’s a hot-headed guy.’ He wanted to use me. So I told him, ‘do whatever you want. You can go tell my father. I don’t care about you or anyone else.’ Then he sent the picture to my father.”

From that moment, Ahmad’s family, particularly his father and brothers, began a campaign of severe violence and social ostracizing that lasted several months. Even when he ended up in the hospital, Ahmad says, “No one asked about me. No one said anything to me. Only my mother was with me. I wasn’t allowed to work. I wasn’t allowed to have my phone. I wasn’t allowed anything… everything was forbidden.”

A few months later, Ahmad says, he was able to work again. One morning, when his father was saying goodbye before Ahmad left for work, he added “Be yourself.” “It felt weird to me,” recalls Ahmad. “Why would my father tell me that? I said thank you, but it felt weird. That evening, I heard my father had died.”

After his father’s passing, his brothers ramped up their violence toward Ahmad — so Ahmad decided to run. After several failed attempts to get a Jordanian passport and leave somewhere else via Jordan — which only brought on more violence — he escaped to Tiberias in Israel.

Hodaya, a trans woman in her early 20s, was born in the occupied territories to a family of seven. Her parents divorced when she was a young child. Hodaya says she ran away from home at age 12 because of the violence she experienced and rarely returned to her family. “I had a really difficult life,” she recounts. “I went out into the streets. I didn’t like sitting at home. I had all kinds of problems. My father didn’t understand me. I didn’t understand myself. I felt I was a woman, not a man.

“I told my father this, and he beat me. He didn’t understand what I had said and what was inside me. He didn’t listen to me. I’d steal, do stupid things. I’d do all sorts of things for food. I worked as a prostitute, used drugs. I went to prison many times.”

When she was about 15 years old, she says, some of her pimps’ customers outed her to her uncle. The uncle had already been abusive toward her, but was now planning to murder her for “desecrating the family’s honor.” She escaped to Israel, but after a few weeks on the streets, while she asked people for food, she was caught and taken to a checkpoint to return to the territories. On her third attempt to enter Israel, she was jailed and later ended up incarcerated four times, once for six months. She did not receive a stay permit until two years ago.

Muhammad also says his family accidentally found out about his sexual identity and tried to kill him. “I was working the night shift at a factory. They found out about me while I was working, and sent two guys to kill me ‘to erase the shame.’ It was a holiday, and there was no passage through Allenby Bridge because of agreements between the Palestinian Authority and Jordan. I was brought back from the bridge because my father works with the PA. I decided to come here [to Israel] to escape,” he says. “I didn’t know there were shelters, and the Aguda [the Association for LGBTQ Equality in Israel], and IGY [the Israel LGBTQ+ Youth Movement] and all that… I came to Tel Aviv because it’s the major city.”

Trapped between homophobia and racism

At-risk LGBTQ Palestinians are caught between a rock and a hard place — homophobia in Palestinian society on the one hand, and Israeli racism on the other. The Israeli LGBTQ community is somewhere in the middle of this spectrum: unable to offer real assistance at best, and exploitative of the Palestinians’ vulnerability and dependency at worst.

After fleeing to Tiberias, Ahmad, like some other at-risk Palestinians, experienced exploitation by Israeli members of the LGBTQ community. “When I was walking on the streets, there was a slightly older guy. He told me, ‘If you want to sleep at my place, you can. I can help you if you want food and money.’ I had only five shekels when I got to Tiberias, and there was nothing else I could do. I said, okay, fine, thanks.

“I went with him to his house, and at night, he made a pass at me. He wanted to sleep with me. I didn’t want to, because he wasn’t my type, and I was scared, and he was Jewish… He wanted to sleep with me, but I had no other way. If he didn’t help me, I’d end up on the street, and I didn’t even have internet access. So I slept with him, but I cried after. I felt really bad. I got a little depressed.”

Muhammad experienced similar attempts at exploitation. “Even before I got to the shelter, I was in really bad form. I complained to people all the time, saying I had to find a place to stay. When I was homeless, lots of Jews said, ‘cool, you can sleep here, but let’s have some fun.’ There are lots of Jews who see this weakness in us, and say, for example, ‘let’s get married. so you can get a permit.’ But it’s all for sex. There are places in the community where they try to take advantage.”

Muhammad adds that since the violence across the country last May, the Israeli LGBTQ community’s attitudes have grown worse: “After everything that’s happened lately, everything has come up to the surface. Even in the LGBTQ community, which is supposed to be the most left-wing, racism came back in full force. There are no more people who believe you’re a normal human being.”

Interviewees have also shared some hard feelings about the Aguda, which coordinates most of the work done in the LGBTQ community regarding at-risk Palestinians. It is important to note that, despite shouldering some responsibility as a key political body for the LGBTQ community, the Aguda, unlike the state, is not formally responsible for protecting at-risk individuals, and it offers assistance as part of a program that has limited resources and relies largely on volunteers.

Still, our interviews indicate that since this is a particularly vulnerable population that often needs immediate assistance, what the Aguda is able to offer falls far short of the needs of LGBTQ Palestinians. As one interviewee said, “I heard a lot of talk from the Aguda, but no action.”

Another interviewee said that on two different occasions, when his life was in genuine danger and he had nowhere else to turn, Aguda volunteers did not respond to calls and text messages, and he had to face the situation alone. “When I send them a message, it takes them at least three days to reply. It’s a really rough feeling, when you find someone to protect you or take responsibility for you, but these people don’t really want to know how you’re doing. It feels like I’m nothing. It’s never a good feeling.”

“On the one hand, I have my Arab society. On the other, I have the state, and then there’s the [LGBTQ] community system, which doesn’t help with anything. And at the same time, they try to pinkwash and say they’re helping.”

Responding to queries about these complaints, the Aguda told Local Call:

“The Aguda Asylum Seeker Department helps hundreds of status-less LGBTQ persons who arrive in Israel after being persecuted in their country of origin because of their identity. However, the Aguda is unable to fully mitigate the state’s harsh and discriminatory reality on this issue.

“Thanks to the department’s efforts, in the past six months, 35 stay permits have been approved for Palestinian asylum seekers whose applications were filed by the Aguda, and dozens of asylum seekers were provided with food vouchers worth thousands of shekels, as well as accommodation.

“We stress that the department does not provide emergency assistance and relies on volunteers, who devote night and day to the issue and follow proper procedures. Additionally, in recent months, the department has hired a coordinator, and we are set to recruit new volunteers within the coming two weeks.

“The Aguda is waging a political and legal battle against the discrimination experienced by this transparent group. Activities include filing court petitions and advocating for policies that benefit asylum seekers. As an example, in recent months, we have met with members of Knesset to demand the advancement of work permits and access to health and psychosocial services for the duration of asylum seekers’ stay permits.

“The Aguda will continue to work to change the harsh reality experienced by asylum seekers and fight for them at the Knesset, the government and the courts.”

Collaborators yes, LGBTQ no

On July 25, the Supreme Court held a hearing in a petition filed by four organizations active on the issue: Physicians for Human Rights, HIAS Israel, the Hotline for Refugees and Migrants, and the Worker’s Hotline. The petition addresses two types of Palestinian refugees in Israel: those at risk due to collaboration with Israel, and those at risk due to sexual orientation and gender identity.

Over the course of the many hearings held in this petition, the state agreed to allow resettled collaborators to work in Israel but, last March, insisted on a “material distinction between the state’s obligations toward Palestinians whose predicament is the result of a connection or suspected connection of one kind or another to the state and its obligations toward Palestinians who allege risk that has no connection to Israel.”

Ahead of the hearing, the counsels for the petitioners, Adi Lustigman, Nimrod Avigal, and Merav Ben Zeev, said:

“We are waiting with anticipation for the right thing to be done and for people who are legally present in the country to be given the opportunity to live in dignity and safety so they can live rather than just breathe. It is the most basic step. Once a person is allowed to remain here in Israel, the fact that they have to have everything they need in order to survive — food, drink, shelter, medical care if needed — must be recognized as well.”

“In its responses, the state is trying to make a distinction between different kinds of risk, effectively claiming that risk due to collaboration justifies eligibility to work, but people who are at risk due to their gender identity or sexual orientation do not have that right. This distinction makes no legal or humanitarian sense.

“The state says applications for work permits can be made, but even the officials who process them know it would require exposing the personal story behind the specific permit — to the employer and to other Palestinians working for the same employer. This completely defies the logic of the protection process. There is no practicable way to get work permits currently, and the fact is people are not receiving them.”

At the hearing, state representatives told the court that the LGBTQ Palestinians can obtain work permits through their employers.

Ofir Shama, the welfare coordinator at the Civil Administration — the arm of Israel’s military government that governs the 2.8 million Palestinians in the occupied West Bank — who handles these cases, told the court that 14 LGBTQ Palestinians from the West Bank who had received work permits in this manner.

This number is clearly insufficient, as the state itself informed the court that there are currently 60 LGBTQ Palestinians from the occupied territories living in Israel. Furthermore, granting work permits remains a problematic option, as the same employers often work with other Palestinians from the West Bank, which could expose LGBTQ Palestinians and endanger their lives.

The distinction Israel is drawing between collaborators and LGBTQ persons is problematic because of a perceived link between queerness and treason among Palestinian society in the occupied territories, which adds a nationalistic element to the persecution over “family honor.” In its report, HIAS writes: “there are ample testimonies and records that LGBTQ living in the Palestinian Authority are persecuted over suspected collaboration with the Israeli security services.”

Long known to LGBTQ activists and organizations, this link was confirmed when, in 2014, veterans of the Israeli military intelligence unit known as 8200 publicly admitted that their duties included collecting information about homosexuals in the West Bank. One former soldier said, “If you are a homosexual who knows someone who knows a wanted individual, Israel will make your life a misery,” adding that, “In the training course, you actually learn and memorize different words for homo in Arabic.”

While Israel’s hasbara machine uses LGBTQ oppression in the West Bank to present itself as an LGBTQ oasis in a homophobic desert, internally, Israel vehemently denies that the PA is persecuting LGBTQ persons or that Israel is in any way connected to it. When it comes to security interests, for Israel, LGBTQ persons and collaborators are one and the same. But when it comes to Israel’s responsibilities toward refugees, LGBTQs are one thing, collaborators are another.

“The policy has been examined and upheld by the Supreme Court”

Pinkwashing has been a staple of Israeli hasbara activities for years; it attempts to distract from the crimes of the occupation by presenting Israel as a liberal, gay-friendly paradise while Arab nations are portrayed as barbaric, violent, and homophobic. Unfamiliar outsiders might expect that a country that takes so much pride in its LGBTQ acceptance — let alone one established as a refuge for those persecuted in their countries of origin — would jump at the chance to help at-risk LGBTQ Palestinians.

But, as Muhammad told us: “When you ask them [the Israeli authorities] why they won’t renew the [stay] permit, they say that the state is afraid you’ll stop emigrating [out of Israel]. Okay, so say I stopped the process. You’re supposed to be happy that I feel comfortable in a country that’s occupying me.”

The Kafkaesque stories of at-risk LGBTQ Palestinians presented here elucidates at least one thing: above everything else, Israel is not a country founded on universal human values, nor on liberalism, nor on gay-friendliness. The Israel of today is founded on Jewish supremacy and an urgent, almost obsessive need to minimize Arab existence and limit the lives of Palestinians in its official borders.

In response to queries from Local Call, the spokesperson’s office of the Israeli Population and Immigration Authority responded as follows: “According to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, the provisions thereof do not apply to Palestinians. Therefore, asylum applications by Palestinians are not considered by the asylum seekers unit.

“We note that according to the recommendations of the inter-ministerial committee on Palestinians claiming risk for reasons other than suspected collaboration with Israel dating November 2014, the proper track for evaluating claims of risk unrelated to collaboration is the COGAT [Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories] welfare coordinator.”

COGAT also responded to Local Call:

“According to the Interim Agreement, cases in which a Palestinian faces risk for reasons other than security are the purview of the Palestinian side. However, exceptional cases are sometimes referred to the welfare coordinator at the Civil Administration, who is permitted to provide assistance in finding solutions within the Judea and Samaria Area and recommend temporary Israeli stay permits in order to save lives.

“We note that the permit is temporary and does not grant status in Israel. We further note that the aforesaid permit is provided according to the recommendations of a team of accredited social workers who assess each case individually.

“With respect to the issue of working inside the State of Israel, we note that residents of the Area [the West Bank] lawfully present in Israel on a temporary basis may file an application for a work permit. Finally, we note that this policy has been examined and upheld by the Supreme Court in a number of cases.”

We also reached out to newly appointed Minister of Health Nitzan Horowitz, asking if he — as the chief policymaker on matters of health and medical services in Israel, and as a gay and human rights activist — was planning to use his powers under the National Health Insurance Act and introduce a special health insurance program for individuals at risk, as he is currently doing for other asylum seekers.

Horowitz did not respond to our request for comment. However, on July 26, Haaretz correspondent Yanal Jabareen asked Horowitz about extending health insurance to LGBTQ Palestinians from the occupied territories during a Meretz faction meeting at the Knesset. The issue with LGBTQ Palestinians, Horowitz told Jabareen, “is not about health insurance but the very right to stay here, health insurance comes later.” Horowitz promised to “look into the matter,” while noting that unlike non-Palestinian asylum seekers, it is not clear exactly how the state registers LGBTQ Palestinians.

A version of this story was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.