On April 29, 1309 — or Dhu al-Qa’da 18 in the Hijri year 708 — the two heads of the village of Zakariyya al-Battikh, on the western slope of the Hebron mountains, presented themselves to the Muslim Waqf endowment of Jerusalem.

In the presence of the Waqf officials, Farraj bin Sa‘d bin Furayj and Nassar bin ‘Amara bin Sa‘id, both of the al-Amer tribe, took an oath promising that the peasants in Zakariyya al-Battikh would cultivate the village land, and that the village’s tax revenues would be put to the benefit of the holy sites of the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque. The scribes of the Waqf administration wrote down the two villagers’ oath, and archived the record in the Islamic court of Jerusalem.

The record of the oath is one of the earliest testimonies to the Arab and tribal identity of villages in the region now known as Israel-Palestine. The Muslim conquest of the Levant took place 600 years earlier, in the 7th century, and we know little about the process of Islamization of the rural population, which had been mostly Christian or Samaritan at the time of the conquest.

Through this 700-year-old document, Farraj and Nassar are among the earliest Arab peasants of Palestine to be identified by name and to speak with their own voice.

The document was discovered in the Islamic Museum on Jerusalem’s Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount in the 1970s by Amal Abu al-Hajj, the museum’s director at the time. It is part of a trove of about 1,000 documents from the Mamluk period that belonged to the archive of the Muslim judge of Jerusalem during that period. Unlike the vast majority of medieval Islamic documents, this set has been preserved intact — perhaps set aside because the judge was investigated on suspicion of embezzling public funds.

In addition to that taken by Farraj and Nassar, this cache of documents includes similar oaths made by headmen in other villages that also belonged to the Dome of the Rock Waqf: Beitunia, Ramallah, Ayn Yabrud, Ayn Arik, and Dura. There is an undeniable continuity between the map of the villages in the mountains of Hebron and Jerusalem at the beginning of the 14th century and current Palestinian towns and villages.

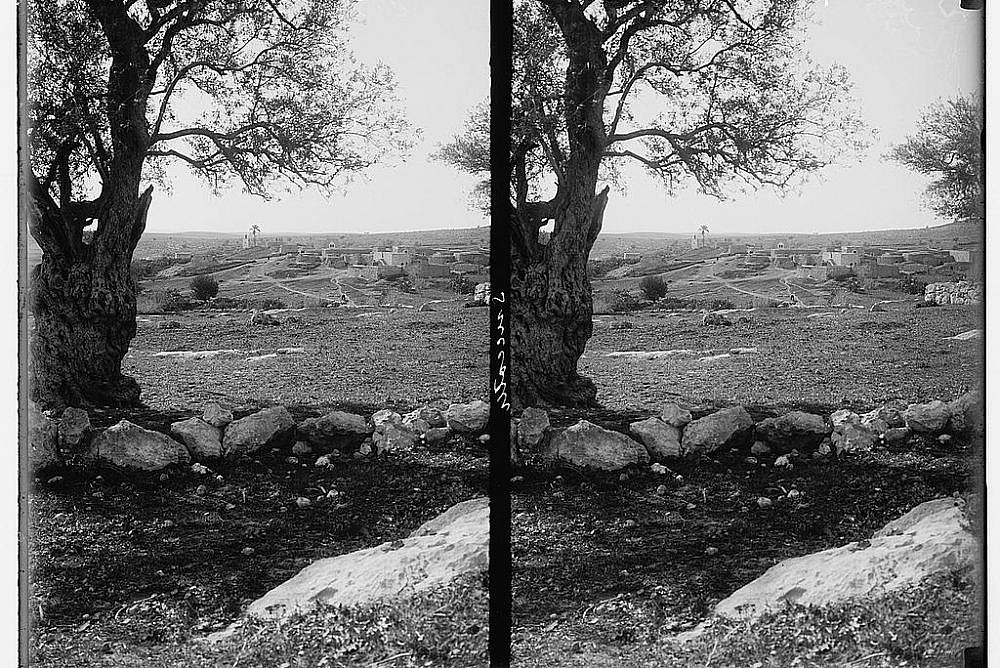

The notable exception to this uninterrupted historical lineage is Zakariyya al-Battikh. Its name disappeared from our maps in June 1950, when the Israeli government ordered the demolition of the village’s houses. It also ordered the expulsion of inhabitants who managed to find their way back home, after fleeing the village during the fighting in the area in September 1948. All that is left of the village are a few derelict structures, the mosque and its minaret, and the building used for the village school. The Jewish settlement of Zecharia was established directly on top of the demolished houses.

The foundation of the State of Israel cut through the deep roots of the Arab Muslim village of Zakariyya al-Battikh. These roots interlocked for at least 700 years, leaving their imprint in the writings of 15th-century European travelers and in the 16th-century tax records of the Ottoman Empire. The demolition of the houses and the uprooting of the inhabitants in 1950 snapped shut a historical continuum, until it was made visible and tangible again by the Mamluk-era document containing Farraj’s and Nassar’s testimonies.

Zakariyya’s lineage may reach even deeper than the 14th century. The Arab village was a successor of the Byzantine Christian village of Zacharia, so called after the biblical prophet whose tomb was discovered in the area in the 5th century. Even earlier still, the hill across from the village is the site of Tel Azeka, a town mentioned in the Book of Joshua. In the historical imagination of most Israelis, there is nothing to bind biblical Azeka and the adjacent Zakariyya al-Battikh. But this is because we have been conditioned to create artificial distinctions between the history of the country and the history of those who populated it.

For the Palestinian artist and writer Zuhayra Khalil Zaqtan, Zakariyya’s past is rooted in the country’s Canaanite identity. In her book “The Ancestors’ Gold,” published in Amman in 2018, Zaqtan constructs a Palestinian Canaanite continuity that is the complete opposite of the Zionist narrative.

She views Palestinian culture and art as the heir of the Canaanite culture that has existed for 6,000 years, arguing from archaeological evidence that the Hebrew conquerors who came from the desert left few material traces. Biblical figures are appropriated and integrated into her historical narrative, so that Melchizedek becomes the high priest and the holy ruler of the monotheist Canaanite-Palestinian nation.

Zaqtan is herself a refugee from Zakariyya, born in Aqabat Jaber camp in the Jordan Valley in 1950, the same year Israel demolished the village. In the introduction to her book, she explicitly links her personal experiences of her journey as a refugee and her intellectual journey toward a pre-Islamic, Canaanite identity. She also publishes her poems on the Facebook page of the “Children of Zakariyya,” where online members are scattered across the West Bank and beyond, alongside photographs of the village’s landscape both before and after the Nakba.

A few months ago, a user uploaded the image of the Mamluk document recording the names of Farraj and Nassar. In messages posted in response, the Children of Zakariyya claimed them as their ancestors, taking pride in the memory of the village.

This year the Jewish settlement of Zecharia will celebrate 70 years since its establishment. Will it, like the Arab village of Zakariyya, enjoy uninterrupted existence for 700 years? Hopefully, it will; the injustices of the past should not be erased by another injustice. Nonetheless, to borrow Zionist terminology, the Arab people of Zakariyya have a moral, historical, and legal right to re-establish their homes alongside the houses of Jewish Zecharia, built in the shadow of the old village mosque.

This article first appeared on Local Call (Hebrew). Read it here.