Four days after Israel’s invasion of Lebanon on June 6, 1982 — whose 40th anniversary fell last month — a company of IDF paratroopers was assigned to guard at least 1,000 detainees in the schoolyard of Sidon’s Saint Joseph Convent School. When the soldiers arrived in the southern Lebanese seaside city earlier that week, they were met with fierce resistance by fighters from the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) as well as Lebanese militiamen, who had been entrenched in a civil war that was now turning into a regional conflagration. It was one of the few instances of Israeli troops entering a major Arab city outside of historic Palestine, and Sidon’s densely populated neighborhoods became the site of intense urban street combat alongside saturation bombing from above.

The stated aim of the invasion was to target PLO militants in southern Lebanon who had been launching rockets at Israeli towns in the Galilee, although a ceasefire brokered by the United States had been reached nearly a year earlier. Despite a pledge to limit the operation to a 40-kilometer incursion, the Israeli government, led by Prime Minister Menachem Begin, also expressed far wider ambitions to rout out Palestinian nationalism. The army soon encircled the capital Beirut, while in Sidon, the ground invasion and bombing campaign destroyed entire homes and hospitals, leveling the Palestinian refugee camp of Ain al-Hilweh.

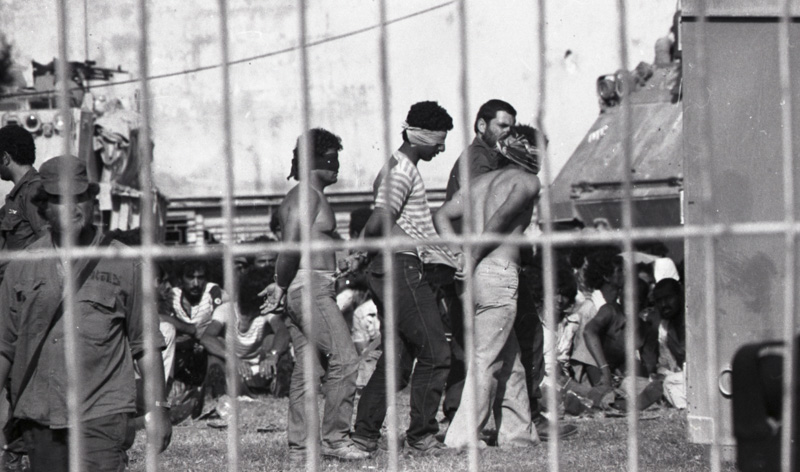

The Israeli attacks induced intense pressure on Sidon’s civilian population, and the IDF ordered those fleeing their homes to gather at the beach. Israeli intelligence handlers drove hooded Palestinian informants to the periphery of the assembled crowds and instructed them to signal from the car windows who were members of Fatah — the leading faction of the PLO, led by Yasser Arafat — or other militia groups. Scores of young men were then arrested and taken to St. Joseph’s, where they were handcuffed and blindfolded in the summer heat.

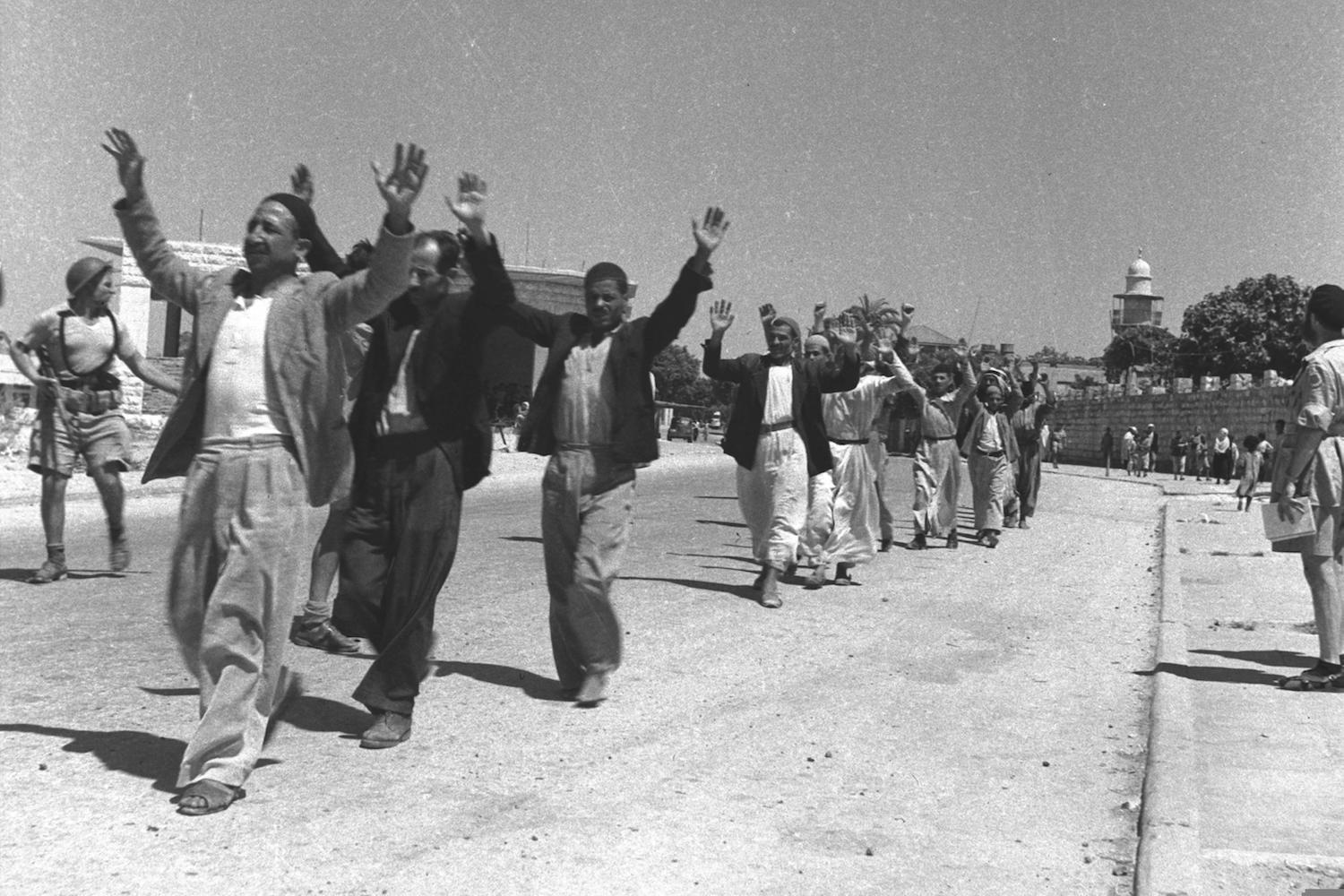

“Schoolyard,” a documentary film by Israeli director Nurit Kedar, revisits the anatomy of the war crime that unfolded at St. Joseph’s over the next three days. It employs a Rashomon-like approach to describing the event, with perpetrators, witnesses, and victims all recounting their experiences. What transpired in the Sidon school, however, is far from a historical footnote; rather, it emerges as a proving ground for Israel’s routinization of violence in civilian spaces, linking the 1982 war with the Nakba of 1948 — and revealing a deeper, harrowing legacy that must be reckoned with.

‘I had the desire to beat them with all my heart’

As news reporting, archival material, congressional testimony, and Kedar’s interviews in the film reveal, most of the Palestinian, Lebanese, and international detainees held at the school were in fact civilians: city residents, aid workers, and doctors from the nearby Red Crescent Hospital, which Israel had bombed during the air campaign. The Israeli reserve unit was ordered to guard the prisoners as they awaited Shin Bet interrogation, positioning armored cars and personnel carriers equipped with machine guns in the corners of the school’s outdoor basketball court to secure the site.

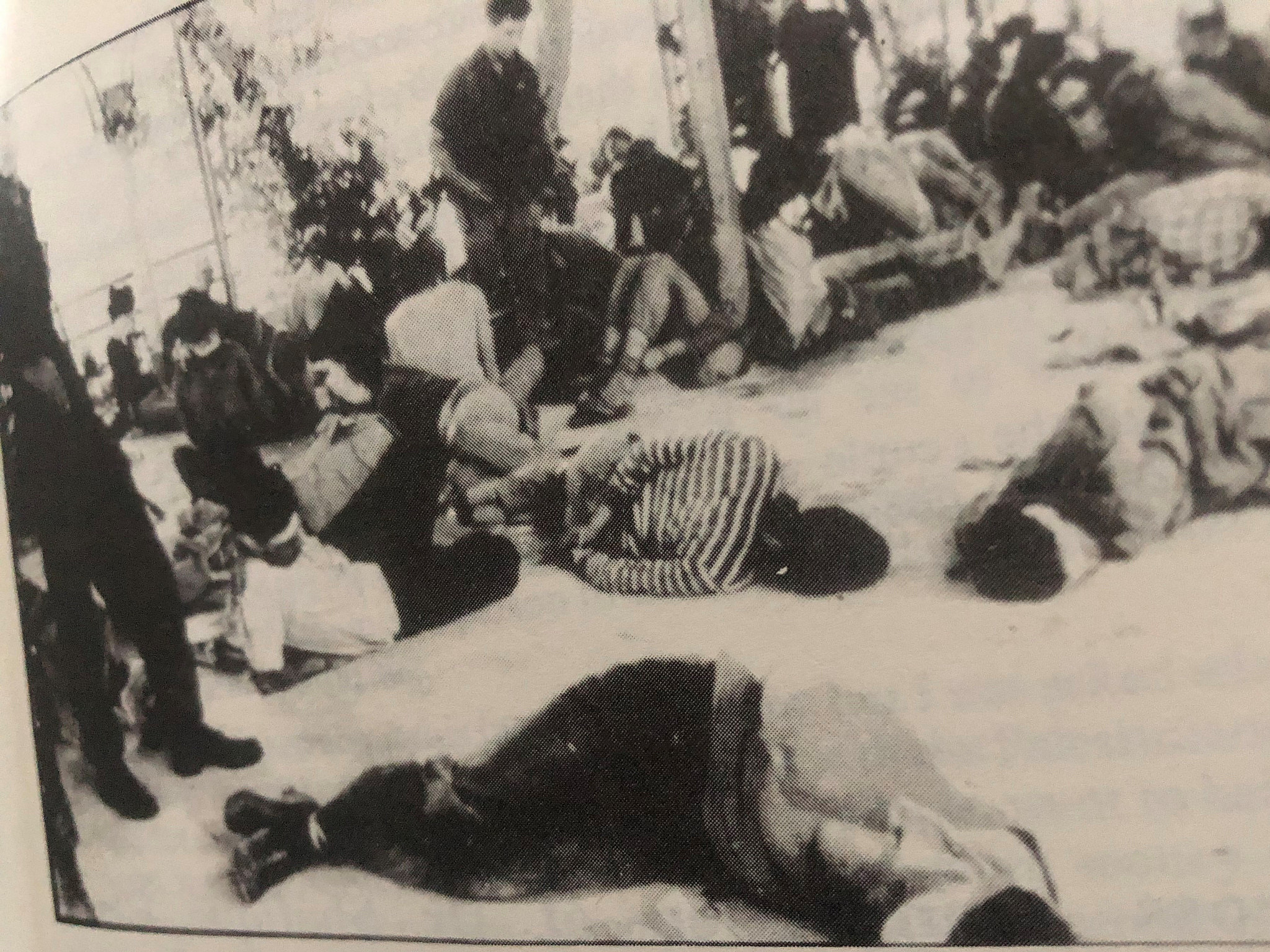

Idan Harpaz, the commander of the IDF company that was tasked with this assignment, appears alongside several of his men in the film to tell the story of what unfolded. The detainees were kept without food and water in blinding heat, sitting cross-legged and forced to relieve themselves where they sat, some drinking their own urine out of desperation. The abysmal conditions worsened, and the soldiers became increasingly nervous.

“Slowly, slowly, clusters of detainees started to move uneasily, demanding water and food,” Harpaz recounts. “It was frightening. We controlled them by shooting in the air… When that didn’t deter them, it was clear I had to employ another method.” The commander soon gave the order for his soldiers to beat the prisoners. “I, too, had the desire to beat them with all my heart,” he admits. “I felt really good kicking here and there. Then I grabbed a wooden stick and went beyond symbolism. It was like diving into cold water — at first you get a shaky chill, but in the end, you warm up.”

One sergeant interviewed in the film, Shmulik Ben Dor, recalls how an IDF major told him that in order to extract information from a particular prisoner who was suspected of being involved in an operation that had led to the abduction of another soldier, he would have to play “bad cop” and act brutally. “I beat him,” Ben Dor says. “It was very hard to do it. But I had to do it. I switched off all my emotions and carried out the task, because it was the sort of task that didn’t, as far as I was concerned, violate my values [here he invokes the Hebrew term degel shachor, a black flag, denoting an instance in which a soldier would be obligated to refuse an illegal order]. It was something that had to be done now, based on the norms I was familiar with.”

When asked by the major to repeat this with another prisoner, Ben Dor said “no no no. I won’t play this game anymore.” But he gave the major another soldier in his stead, “and unfortunately, that other soldier did his job in an incredibly brutal manner. He must have used some sort of tool, and injured him badly. He gouged his eye out.”

Eyewitnesses have provided extensive details of the relentless blows and the violence that ensued from these orders. Dr. Chris Giannou, a Canadian surgeon working with the Palestine Red Crescent Society who was detained at St. Joseph’s, testified before the U.S. Congress several days after his release:

The scene in the schoolyard… was one of savage and indiscriminate beatings of the prisoners by the 40 Israeli guards. A prisoner would call out for water and [be] told that there was none. When he continued to call out, he would be insulted and then a guard would wade into the crowd and start to beat him. The physical abuse ranged from simple punching and kicking to beatings with wooden sticks, plastic hose or even a bunch of pieces of rope with nuts and bolts tied to the ends; a sort of modern cat-o-nine tails. One Palestinian, Dr. Nabil [Shuaby] was at one point hung by his hands from a tree and beaten. An Iraqi surgeon, Dr. Mohammed Ibrahim, was beaten by several guards viciously, and left to lie in the sun with his face buried in the sand.

Giannou’s testimony was further corroborated by two Norwegian aid workers, Dr. Steinar Berge and Øyvind Møller. According to the report Møller gave to the Norwegian Department of Foreign Affairs about one incident he witnessed, an Israeli soldier “drove his knee with full strength up the prisoners’ groins, one after the other. When the prisoners subsequently bowed forward the soldier hit their necks with his hand and they fell onto the ground. Then the soldier kicked them in the face and in the stomach. The prisoners were then gathered in a heap, where they crouched with pain.” There were basketball poles at both ends of the schoolyard where “prisoners were regularly tied up to those poles and beaten, often left there hanging.”

After Israeli buses finally arrived to transport the detainees from the schoolyard to another site, Harpaz and his men found seven dead bodies lying on the ground: those of Mohamed Akra, Abudi Abrusli [written as Abed Kuborosli in some records], Yahya Musri [Yihaya El Masri], Samir Sabbah, Mohamed Mansour, all of whom were Lebanese; Mohamed Abu Sikini [Mahmoud Abu Sakina], a Palestinian; and an unnamed Egyptian. Dr. Giannou was asked by an Israeli soldier to examine some of the cadavers to confirm they were dead. The army then deposited their bloodied corpses at the gates of the public cemetery in Sidon, where they were buried in a mass grave by the local Lebanese gravedigger.

In his congressional testimony, Giannou stated that he saw Israeli officers and the military governor of Sidon, Col. Arnon Mozer, “being witness to these beatings and not doing anything about it.” He also noted there were some guards who attempted to stop the beatings, “and on several occasions, actual arguments breaking out amongst the guards, between those doing the beating and those who attempted to have them cease.” All this indicates a clear violation of the 1949 Third Geneva Convention, particularly Articles 13 and 20, on the humanitarian treatment of prisoners of war during captivity.

Despite the intimate details — which were also recounted in the New York Times’ coverage of Giannou’s testimony — an Israeli press spokesman called the surgeon’s statement a “total lie.” Giannou and other foreign doctors filed a complaint to the IDF about what they witnessed, and the military police opened an investigation. The story was also covered by the prominent journalist Robert Fisk, who quoted an Israeli spokesman promising the report would be made public. But the investigation did not lead to any operative conclusions, and the story receded from view. As Harpaz told Kedar, “A complaint was filed, the IDF interrogated me, but did nothing with it.” To this day, not a single Israeli official or soldier has ever been charged.

Dov Yermiya, an Israeli lieutenant colonel who oversaw civilian aid in Sidon and became a prominent critic of the 1982 war, witnessed the beatings at St. Joseph’s and reported some of the cases to the military authorities. He later recounted a similar incident in Lebanon that had occurred decades earlier, during the 1948 war, in which his intervention had led to an Israeli officer being charged with the murder of 35 Arab prisoners in the Hula Valley. The officer, Shmuel Lahis, was sentenced to seven years in prison, but his punishment was reduced and he did not serve any jail time. Lahis was eventually granted presidential amnesty and later appointed director general of the Jewish Agency. Reflecting on the parallel cases, Yermiya said “If this happened then — and ever since then the wars and occupations have continued — even if the Army were filled with Angels, they would turn into soldiers of the Devil.”

A receptive time to own up to a war crime

From his home on the Greek Peloponnese, Dr. Chris Giannou reads from the original Congressional testimony he gave in 1982, and Dr. Steinar Berge recounts memories of what he witnessed from Norway — two incongruously peaceful surroundings in which the details of the beatings in Sidon are resurrected in the film. Interwoven are vivid photographs and video clips of the schoolyard and blindfolded prisoners, and the account of Nabih Shuaby, the Palestinian doctor who was hung by his hands from a tree and beaten. Shuaby’s harrowing description of near death in captivity, told with quiet dignity from his Amman sitting room, lends the documentary its backbone.

“I was picked up from among the dead and returned to the living,” Shuaby says, recounting how he was mistakenly left behind with several other bodies. He remembers slipping into a coma and hallucinating during his ordeal. “I began to imagine I was at the theater, rather than a classroom with soldiers, in a school with the Israeli army.” As Shuaby describes the torture he endured, he points to the scars that remain on his face, from an abscess on his cheek to a wound on his lower lip. At one point in the film, he gets up from his chair to reenact how he was tied up, the camera gazing at the doctor’s weathered hands clasped firmly behind his back.

By decentering the voices of the perpetrators in this way, Kedar signals a departure from the “shooting and crying” genre that mars the work of many of her Israeli colleagues, such as Ari Folman’s visually arresting 2008 “Waltz with Bashir,” which sparked significant debate over the ethics of representing wartime trauma. Still, despite its laudable effort to expose a dark chapter of 1982, “Schoolyard” remains confined by political and moral limitations.

In her study of documentaries about the Cambodian genocide, the Israeli film scholar Raya Morag speaks of “Perpetrator Cinema,” which allows survivors to confront their aggressors in “a direct, non-archival, face-to-face confrontation,” which in turn opens a space for transforming power relations and creating a different form of ethics.

Kedar’s film sits firmly in the genre of “perpetrator trauma,” creating a confessional silo in which the soldiers speak only to her, the Israeli insider who can coax their guilty or prideful confession. We are witness to snippets of recollections and the performance of violence as the soldiers recount the beatings, a method that invokes Joshua Oppenheimer’s haunting 2012 documentary, “The Act of Killing,” about the mass executions of accused communists in Indonesia in the 1960s.

But unlike the Indonesian subjects in Oppenheimer’s film — who seem rather delighted to reenact their fatal violence now that the fighting has ended — Kedar’s interviewees are intertwined with the context of ongoing, daily acts of anti-Palestinian aggression that continue in Israel and the occupied territories, and their confessions still conjure some degree of discomfort as they ruminate on the moral implications of their deeds.

At times in the film, the offending Israeli soldiers try to justify their actions, recounting them as examples of necessary self-defense or the result of orders from on high. Echoing Ariel Sharon’s false rhetoric around the victims of the Sabra and Shatila massacre, some of Schoolyard’s soldiers slip effortlessly into talking about defending themselves against “terrorists,” foreclosing the notion of a civilian victim in an encaged space filled with doctors, aid workers, and other non-combatants.

Tzur Shezaf, the unit’s combat medic, says he argued with Harpaz about this: “Idan, we don’t have to do it. There’s no reason to beat them. It isn’t good.” He later describes watching a prisoner being beaten to death by other soldiers: “It was the first time in my life — and I was a bit of an alley cat growing up, and had been in my fair share of brawls — it was the first time in my life that I saw a man beaten to death. They just beat him to a pulp. Literally. I mean I remember it because there was nothing left of him. He became a kind of groaning sack that could barely move.” When asked about his participation, Harpaz remarks “I felt like I couldn’t hold myself back. It would be wrong if I wasn’t there, if I told everyone to hit them but I didn’t do it myself.”

The collective sketch is a fitting document of the callousness, discomfort, and suppressed guilt that marks contemporary Israeli society and its dehumanizing treatment of Palestinians. As with the destruction of Palestinian villages in the 1948 war, what happened in St. Joseph’s schoolyard was never entirely hidden from view. In 1990, for example, Shezaf himself wrote of the war crime in a widely read four-page cover spread in the Hebrew newspaper Hadashot, sharing his own diaries and meditating on the limits of his ability to stop the beatings.

Seen in this light, the film’s true revelation is the need of Harpaz and the other soldiers to speak of their crimes. Rather than hide or remain silent, the soldiers find some comfort, or perhaps even absolution, in divulging to Kedar the details of their actions without ever having to fear accountability for them.

For his part, Harpaz told a Haaretz journalist that he found it difficult to watch the film’s August 2021 premiere in Jerusalem. “I left depressed; it was a blow to the stomach and I did not understand why. Because I had seen the material before, there was nothing new there, and I did not understand why it affected me like that,” Harpaz explained. “Only a few days later did it dawn on me. That Nurit [Kedar] brought the doctors, whom I remember, and they described what they experienced, this was 10 times stronger than what we could describe.”

The former commander blamed forces greater than himself, insisting that the soldiers were “as humane as possible, but in a situation like this it is impossible.” “It was the most backward task there could be, helping military police keep the detainees,” Harpaz explained, “and suddenly everything turned upside down, and I became responsible. I ran to the military governor and the brigadier general and reported that it looked bad and that we were being beaten, and yet — suddenly we lost control.”

Still, with all his discomfort, Harpaz called Kedar to stress that she must acknowledge that he provided a copy of his wartime diary, in which he divulged the details of what happened. Harpaz’s need to disclose that fact — to publicly implicate himself in the horrific crime — raises important questions about motive, consequences, and the search for recognition.

Unlike Shezaf’s dissenting account in 1990, or the release of Waltz with Bashir in 2008, Harpaz’s behavior suggests that the early 2020s are a more receptive time to own up to a war crime in Israel. Like Dov Yermiya’s warning about 1948, what may have been seen by some as a red line in the past can now be disclosed with full impunity, the fear of exposure giving way to a compulsive form of articulation.

The Israeli public’s embrace and the early release of Elor Azaria — a convicted army medic who was caught on camera shooting dead a writhing Palestinian attacker on a Hebron street corner well after he had been immobilized in 2016 — is a clear indicator of how the boundaries of acceptable violence are shifting. As Azaria’s case shows, although some war crimes may now be documented and admitted, the impunity remains. To speak on camera instead becomes another venue in the Israeli search for exoneration, without ever having to face real accountability.

“Theoretically we were not guilty of anything,” Harpaz told the Haaretz journalist after the debut. “After all, we went and warned in real time about what was happening there, we went to the highest levels, we also told about the (lack of) food and water and also about the beatings. I cannot say today that I should have done something else.”

These words of justification are belied by Harpaz’s severing of his actions from the outcome that follows. “And suddenly it happens. Suddenly when they cleared the yard in the afternoon, there were dead people there. So it’s something that sits on you all the time, the question is whether we should have acted differently anyway.” In Harpaz’s telling, it is as if the “dead people” just appeared, materializing of their own volition. The distance he places between himself, his soldiers, and the bodies in front of them mirrors the eroding line of Israeli collective consciousness in owning up to the moral consequences of state and individual violence, which continues nearly-unabated today.

Rather than confront the unnamed victims, Harpaz’s story is, yet again, one that revolves around the trauma of the soldier. This, too, informs wider public sentiment in Israel, where the reckoning with causality is constantly deferred or excused. In explaining his reasons for participating in Haaretz:

Harpaz hopes that “Schoolyard” will be able to provoke a discourse on “ethical injury” or “ethical trauma”: psychological terms that describe the damage done to a person’s conscience when he performs acts that are inconsistent with his value norms or his code of moral conduct, or fails avoid them. “It’s something that is not talked about enough: people who do things and in retrospect feel they should not have done them morally,” Harpaz says. “And this needs to be talked about, because soldiers in the territories certainly come to these places today. A lot of civilians die in the territories, but no one talks about what it does to the soldiers. This is a neglected issue and these people need treatment.”

Harpaz is thus an ideal guide to the pathologies of Israeli society, plagued by an inability to reckon with power, only able to see victimhood at the hands of others. Such pieties ring hollow when uttered within the confines of a system that refuses to acknowledge its own agency as a purveyor of violence, a system so accustomed to speaking in dehumanizing terms about its Arab and Palestinian subjects.

From Tantura to Sidon

Schoolyard has enjoyed considerable attention in Israel, with the public broadcaster KAN airing an abridged version of the film last October and receiving an honorable mention at the 2021 Jerusalem Film Festival. But Kedar’s early struggles to secure funding for the film suggest a general reluctance to revisit the Lebanon War.

This is partly the legacy of a so-called “war of choice” that was highly unpopular in Israel, as the public grappled with misguided war aims and searing events such as the Sabra and Shatila massacre. The social rupture spawned military refusal, public protest, cultural production, and anti-government unrest that bolstered dovish movements such as Peace Now, Yesh Gvul (which supported Israeli conscientious objectors), and other civil society organizations. The impulse toward selective amnesia is also a byproduct of Israel’s 18-year occupation of southern Lebanon, whose casualties shaped successive generations of soldiers and instigated the grassroots Four Mothers Movement, which contributed to the public pressure for withdrawal in 2000.

In its aftermath, the Lebanon War spurred a movement of historical reckoning with Israel’s origin story. The overreach of the invasion and the domestic political climate pushed scholars such as the “New Historians” to revisit the founding myths of Zionism and the state, aided by archives from the 1948 war that had opened at the end of a mandated 30-year declassification period. If Menachem Begin had deceived the public about his intention not to go further than 40 kilometers past the border in June 1982, might David Ben Gurion’s claims about Arab aggression and Palestinian flight in May 1948 also merit investigation?

This year’s 40th anniversary of the Lebanon war similarly coincides with increased openings in key collections like the IDF Archive, along with a greater willingness of army veterans to speak publicly about what they experienced. The conjuncture will no doubt generate new forms of historical memorialization, and an attendant risk, as Israeli scholar Asher Kaufman wrote, is that 1982 might be remembered as an exonerated war, or even “a source of national pride.”

As the voices of soldiers from 1982 reach wider audiences, Lebanese and Palestinian survivors are confronted with a public spectacle of Israeli impunity, compounded by the political success of thoroughly corrupt Lebanese politicians who were agents of wartime destruction, and bolstered by the Israeli-Arab normalization deals that have sidelined Palestinian political aspirations. In this sense, the 1982 war has not truly ended, with films like Schoolyard highlighting a clear historical thread that tells us as much about the present as it does about the past.

The recent documentary “Tantura” by Alon Schwarz exemplifies this thread. The film includes testimony of Alexandroni Brigade soldiers who massacred over 200 Palestinians in a seaside fishing village during the 1948 war, an incident that was repeatedly denied by Israeli officials, but remembered all too well by witnesses and survivors, and extensively chronicled by Palestinian writers, scholars, and filmmakers such as Haj Muhammad Nimr al-Khatib, Mustafa al-Wali, and Ibtisam Mara’na.

Notably, a Hebrew masters thesis about what happened in Tantura, submitted at the University of Haifa by the historian Teddy Katz, was withdrawn after false accusations that he fabricated his extensive source material. In fact, Katz interviewed the same perpetrators of the war crimes who now speak openly of their actions on camera, collecting over 100 hours of testimony from Palestinians and Jews.

As Schwarz’s film demonstrates, it is often not until Israeli soldiers or directors narrate what transpired that public attention is finally paid, even fleetingly, to such atrocities. Palestinian testimonies of the Nakba — like those eyewitnesses to the schoolyard killings in 1982, or more recent violence in Gaza and the West Bank — have a track record of being greeted with disbelief, if they are even registered at all. Time has a way of correcting the persistence of denial, as does the identity of the messenger.

The climate of perpetrator trauma and the demand for exoneration has deeper roots in Israeli history, distinguished by a pattern of immoral action followed by revulsion since the Nakba. In the past — whether in S. Yizhar’s fictional novella “Khirbet Khizeh,” or the tailored account of soldiers who participated in the 1967 war and its aftermath as part of Avraham Shapira and Amos Oz’s book “The Seventh Day” (later adapted into a documentary film) — the hint of embarrassment and mortification lent a semblance of moral seriousness to the exercise of memory. But we have entered the age of impunity, where the violence is justified as necessary, as a precondition to survival, spoken about without hesitation.

Israeli historian Benny Morris’s frank interview with journalist Ari Shavit during the Second Intifada is emblematic of this shift. Morris described the ethnic cleansing of Arabs as the only way to prevent the genocide of Jews, a narrative of “necessity” that the Israeli right would promote to insist that the Nakba did not go far enough.

Even Shavit seemed indignant at the time, until his own writing on the depopulation of the Palestinian city of Lydda appeared in the pages of The New Yorker. As Shavit wrote of the perpetrators of that war crime: “If need be, I’ll stand by the damned, because I know that if not for them the State of Israel would not have been born. If not for them, I would not have been born. They did the filthy work that enables my people, my nation, my daughter, my sons, and me to live.”

The Israeli veterans of Tantura might once have conspired to cover up the indiscriminate killing of Palestinian prisoners after the end of battle, but now, their deeds are openly discussed on camera. This is not a reckoning in the service of repair. Consider the recent film of Pedro Almodóvar, “Parallel Mothers,” and its moving final scene as the descendants of Franco’s dictatorship stand together while forensic experts uncover a mass grave outside their village, their act of collective excavation signaling a way forward from the violence of history.

In contrast, talk of excavating the mass grave in Tantura at the end of Schwarz’s film is greeted by one cantankerous historian, Yoav Gelber, with disbelief. The grave sits under the parking lot of Nahsholim beach without any demarcation, let alone a commemorative plaque. In the final scene of Schoolyard, a local filmmaker is brought into the Sidon cemetery to interview Ahmad Waise, the son of the gravedigger who helped his father bury the seven men in the summer of 1982. As he points to their mass grave, the credits begin to roll, the faces of some of those who were killed flickering across the screen.

Moral decay

Beyond the pathos for the deceased, what do these stories tell us? Do such films truly matter in the absence of justice, amid ongoing impunity? One overwhelming impulse when watching Schoolyard, like Tantura, is to see the perpetrators investigated and charged for their crimes. Rather than watch the camera hover over their aging faces, one wonders if it would not be more efficacious to share the evidence with lawyers to begin international criminal proceedings against them.

Kedar’s aims are more modest, as she explains in Haaretz. “On the one hand you say okay, a lot of things happen in wars, but it still does not justify what happened there. To me, it’s awful that since World War II all wars in the world have been an army against civilians. In wars like this, that’s what happens. I do not pretend to be a judge, to determine who is right and who is not, but I do want to put a mirror in front of them.”

But who exactly is watching? On recent visits to Tel Aviv I was struck by the ever growing disconnect between daily violence against Palestinians and ceaseless economic expansion in the city. It has not diminished Israeli enthusiasm for obligatory military service, or deep devotion to the army. Colleagues spoke openly of children and grandchildren wanting to join Unit 8200, the IDF intelligence corps that is very popular with the upper-middle class Ashkenazim of the Tel Aviv metropolitan area. For those wishing to avoid combat roles, conscripts could instead work on covert intelligence operations before fast-tracking into tech sector careers.

In this 21st century Israeli landscape, the documentary may be politically extraneous, but it is a mirror to shifting societal norms, of a moral universe moving from angst and fear of persecution toward a willingness to disclose past indiscretions, even with pride. The need to speak of war crimes suggests a particular form of guilt and a warped memorialization practice that is taking shape. While it links 1982 with 1948, it also evinces an inability to break free of the past in grappling with contemporary instances of violence.

Consider the fatal gagging of 78-year-old Palestinian-American Omar As’ad by Israeli soldiers in the West Bank village of Jiljilya in January, which induced a heart attack and led to his death, without repercussions. There is depravity and numbness at the heart of official and public responses to such egregious war crimes: what might have once been seen as a “black flag” order that necessitates refusal is now defended in many corners, a clear indicator of where Israeli moral decay has led.

When crimes are not named as crimes and bodies simply materialize on the ground — whether in the mass grave of Tantura, a Sidon schoolyard, or a road outside of Jiljilya — the perpetrators are left to speak into a void, wrestling with their own demons but not with the structures that continue to perpetrate such violence. It is a deceptive space for reflection and handwringing because there is no absolution without accountability, and no ability to look backwards without justice.

The Lebanon War offers important lessons in this regard. Days before Harpaz and his men beat prisoners at St. Joseph’s, an Israeli reserve pilot refused to carry out an order to bomb a nearby school in Sidon, the subject of the Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari’s captivating installation “Letter to a Refusing Pilot.” Such instances of dissent are receding from view, demarcating the limits of refusal in an age when guilt is so readily confessed. Today’s IDF also remains resistant to investigating accusations of illegal action, far less encumbered by international opprobrium or condemnation than it might have been in the past.

At the micro level, this dichotomy between individual acts of bravery and structural violence evokes the battle between those who beat prisoners and those who dissented in the Sidon schoolyard. It is why so many Palestinians are caustic about the revelations from Israeli soldiers in Breaking the Silence who have witnessed war crimes: their anguish is seen as a protest discourse rather than a search for justice, while their testimonies are incorporated into a wider process of ongoing colonization. Within the Israeli political culture of 2022, it is the beaters who are riding high, even as the dissenting voices help sustain the ethos of the state.

On the same morning that the Palestinian journalist Shireen Abu Akleh was killed while reporting on an Israeli army incursion into Jenin, I received an email from the IDF Archives, containing a file with video footage I had ordered for a book project about the 1982 war. One of the films recorded the evacuation of a Lebanese family from the outskirts of Beirut during intense shelling, a mother and father clutching their children as they raced to their car and froze in place as bullets whizzed by.

The look of terror in the face of their young boy stayed with me as I scrolled through clips of the scenes unfolding in Jenin. Abu Akleh’s colleague Shatha Hanaysha had a similar look of anguish standing by the intrepid reporter’s slouched body, the very same image of helplessness and shock in the face of violence.

A predictable battle over who was to blame for Abu Akleh’s killing flooded social media. Prime Minister Naftali Bennett published videos from his Twitter account in an attempt to prove that it was a Palestinian gunman, not an Israeli sharpshooter, who was responsible for Abu Akleh’s death. Nachman Shai, Israel’s diaspora affairs minister, wrote that her death was “very sad & regrettable” adding that “Responsibility for her death must be determined thru [sic] a speedy trustworthy & transparent investigation. The Palestinians must allow a joint investigation, inc. with international officials, in order to do so.”

The pattern of accusations, denials, and calls for investigation were yet another turn on a dehumanizing merry-go-round. As a historian researching 1982, the public statements had a familiar ring of well-trodden hasbara honed during Israel’s entry into Beirut, helping to combat the critical media coverage.

Ironically, it was Shai who was castigated the next morning for suggesting on the radio that an Israeli investigation into Abu Akleh’s death might not be deemed credible, given the track record of such inquiries. “With all due respect to us, let’s say that Israel’s credibility is not very high in such cases,” he remarked.

Right-wing critics, of course, pounded Shai’s statement — but the minister can hardly be lionized as a liberal Zionist hero. In The New York Times article about Chris Giannou’s Congressional testimony 40 years ago, the Israeli spokesman in Washington who denied the beatings in Sidon was none other than a young Nachman Shai himself, calling Giannou’s claims “a total lie.” One wonders what the minister would make of the Schoolyard testimonies today.

No one has been held to account for beating to death seven men in Sidon, and it is seriously doubtful they will ever be for Abu Akleh’s killing either. Investigations by the New York Times, CNN, and Associated Press confirm that she was likely targeted by Israeli forces, while a Palestinian probe concluded that it was deliberate. Israeli claims of a full investigation have been met with criticism and disbelief.

The possibility of consequences, however, have already been circumscribed by Israel and its external supporters. The army decided there was “no need” to open a criminal investigation due to the “nature of the operational activity, which included intense fighting and extensive exchanges of fire.” On the eve of U.S. President Joe Biden’s visit to Israel this month, the State Department issued a closely crafted statement concluding “that gunfire from IDF positions was likely responsible for the death of Shireen Abu Akleh,” but “found no reason to believe that this was intentional.” In dismissing the very notion of intentionality, the overarching structure that produces and legitimates such violence remains unchallenged.

Abu Akleh’s death thus illustrates one fundamental lesson of 1982: that without redress for historic and ongoing war crimes, Israeli society will remain in the throes of violence, stripped of hindsight, unable to confront the consequences of individual or state action. Without accountability, perpetrators will continue to recount their deeds in private and before the cameras — with contortion, pride, or by lashing out at victims — while lacking the moral agency or the attainment of psychological resolution they so desperately seek.

This is a position of both strategic and ethical weakness, pitiful but not tragic, as it is Palestinians who will continue to pay the price for impunity. As long as Israelis cannot reckon with the implications of state power and sovereignty in both its national and colonial guises, there will be many more such crimes yet to come.