“The fact is that we are ill, very ill” wrote Jean-Paul Sartre to the French in 1957, commenting on the blindness of his own society vis-à-vis their responsibility for colonial rule in Algeria. The fact is that we, too, are ill. Very ill. And acknowledging one’s own illness is, for me, the hardest phase.

Growing up in Israel, under a political system that manifests the Zionist idea exclusively, we proudly believe in a clear distinction between “our” Zionism as it has been practiced inside the Green Line, and the settlers’ project beyond the pre-1967 lines. But hard as it is to admit, this logic is artificial, and it is blinding us.

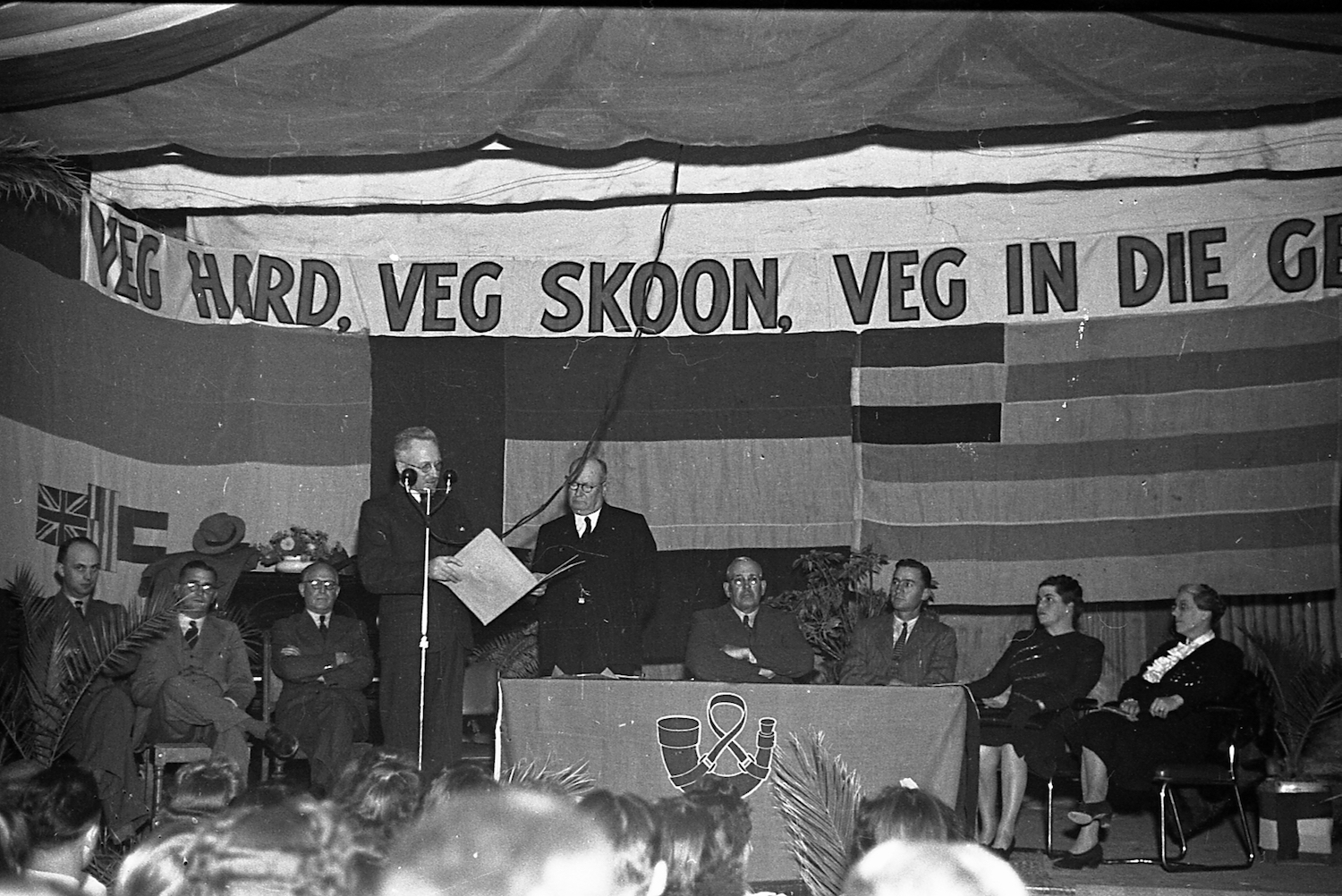

In recent years, I have spent a great deal of time in South Africa. I have been particularly drawn to a group smaller than 10 percent of the population: White Afrikaners, the descendants of Europeans who arrived at the southern tip of Africa in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the early 20th century, with British colonialism coming to an end in Southern Africa, the Afrikaners gained political control over the land. In 1948, they established Apartheid as a political system that lasted for 50 years before it was abolished in 1994.

During the Apartheid years, only very few Afrikaners succeeded in recognizing their own illness (today it is acknowledged by almost all Afrikaners who desire to keep it a thing of the past). Those precious few faced a daunting impasse: they realized that something in the narrative of their upbringing was fundamentally off, that the logic of white domination over blacks — the numerous justifications offered notwithstanding — could not be valid.

Acknowledging this involved grappling with the most fundamental assumptions of their social, familial, and professional circles. Upending Apartheid’s justification meant turning their backs on family, nation, and state. They were seen — correctly — as traitors. But they never betrayed their motherland, only its regime.

Their impasse was first and foremost internal: they had no alternative narrative to that of the regime through which they could imagine themselves. While the Black Consciousness Movement, which was evolving in South Africa at the time, provided a solid backbone of identity for the struggle against Apartheid, it did not speak to them as whites. Since the regime equated itself with Afrikaner nationalism, it followed that being anti-Apartheid meant being anti-Afrikaner. Thus, being an Afrikaner against Apartheid meant opposing one’s very self. One Afrikaner explained it to me: “We had to ask ourselves: what does it mean to be who we are — Afrikaners — without Apartheid? We discovered we had no answer.” This is the essence of the illness.

“What does it mean to be Jewish-Israeli without Zionism?” A question I never asked myself.

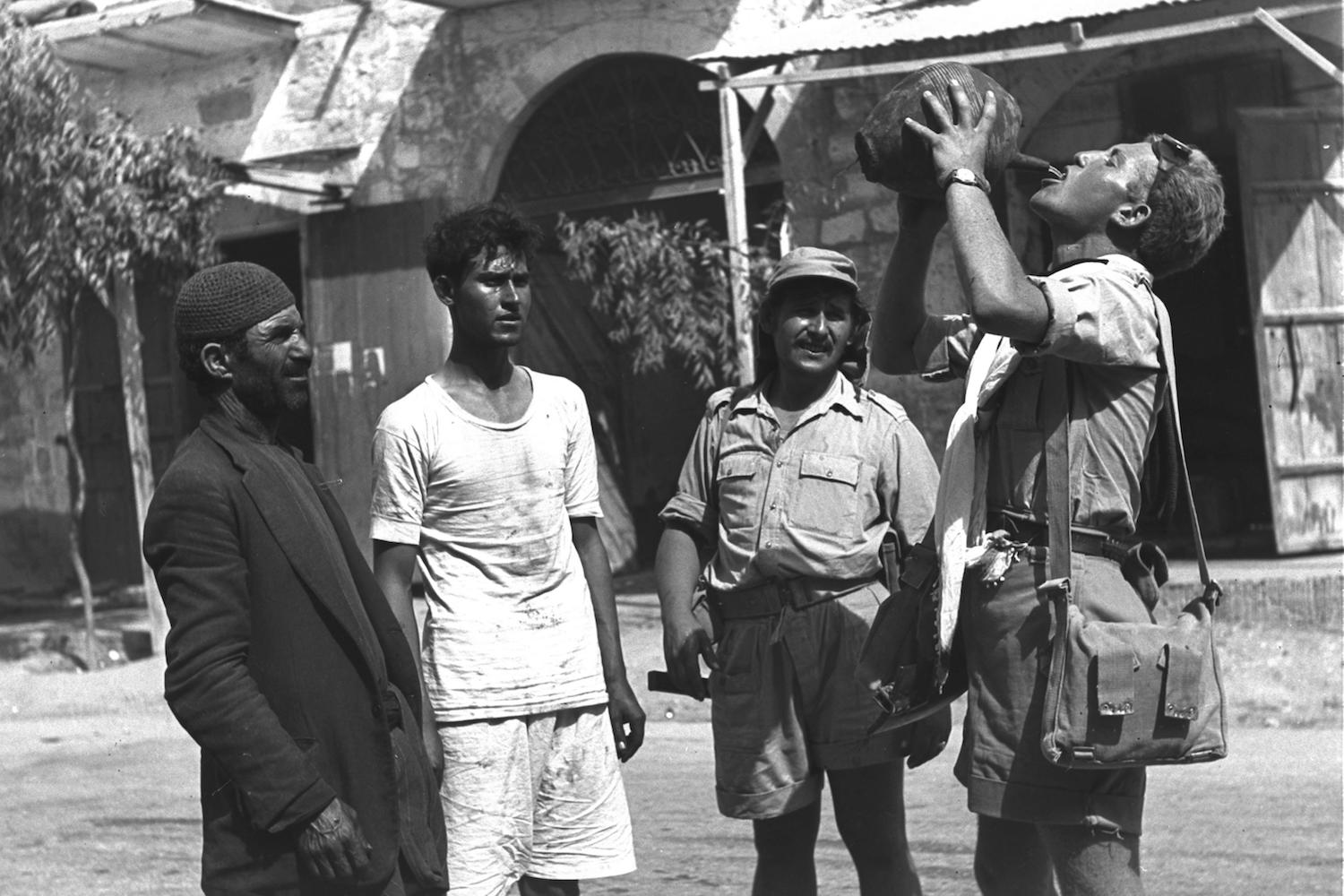

The Zionist regime (Zionism as it has been practiced, not its ideological or philosophical “could have been” version) never did much by way of democracy. Already in its early years, the Israeli regime worked to secure a Jewish majority through the likes of the Absentees’ Property Law and the Law of Return, and to impose a two-tiered system via a military apparatus imposed on Arab areas in the new Israeli state. 1967 saw a new-old task added to our national project: settling and controlling territories beyond the internationally recognized Green Line. The Jewish-Zionist left was given a new issue to struggle over: “the occupation of the territories,” which while in line with the original settler logic underlying Zionism (“our right to the land”) was far uglier in the eyes of both left-leaning Jews, and the world.

Our illness did not begin in 1967. For those unwilling to cast doubt upon the narrative of exclusive Jewish sovereignty over the land, marking the beginning of “a different story” in 1967 is a convenient way not to look the illness in the eye. We can tell ourselves that treating the symptoms of occupation — if only that was possible — would have paved the way toward continuing the “unblemished” Zionism project.

In recent years, events on the ground have disrupted us from continuing to tell ourselves this story. Almost all political parties representing Jewish Israelis reiterate to Palestinians citizens their exclusion from true egalitarian partnership in Israel’s governance. As de jure annexation of large parts of the West Bank — with support from much of the Jewish public — is fast approaching, it is becoming harder and harder to hold on to distinguishing between “Israel” and the “occupation.”

A good starting point can be the infuriating question often posed to us by the right: “What is the difference between Ramat Aviv (the Tel Aviv neighborhood built on the ruins of Sheikh Muwannis) and Kiryat Arba (the West Bank settlement near Hebron)?” It is a question we too should dare ask — not in defiance, but with courage, humility, and sincerity. For what is, in fact, the difference — when looking through the lens of national and historical justifications — between applying Zionism over Yaffa or al-Lydd, and applying the same regime over Bethlehem or Nablus?

The queasiness we feel when faced with such questions is a symptom worth thinking through, as it brings us closer to our true illness: that we do not have a national or group identity that neither involves nor depends on subjugating Palestinians under Jewish supremacy. I fear we never had one.

The Jewish-Israeli left has never come up with an alternative narrative to that of the regime. When such attempts were made, they remained on the margins, and were never adopted wholesale as the basis for a broader liberation struggle (and of this regime, we Israeli Jews must also liberate ourselves, not only the Palestinians).

Presenting such ideas in Israel today may be considered treason, yet it is essential to sincerely think them through if we are to grow a new politics — and a new identity, for us to struggle in its name. This new political Jewish identity will have to acknowledge the wrongs of the past, but not be subjugated by them. And it will free us not only from an identity defined by fears and threats, both real and imagined, but also from the knowledge — repressed, hard to put into words — that we, too, are ill, very ill.

This article was originally published in Hebrew on Haaretz. Read it here.