After 65 years of ‘peace talks,’ Ariella Azoulay believes what is needed now is not a new vision but an old one – one envisioned by people who lived in Palestine before the curse of partition.

By Ariella Azoulay

Over the past few years, it has been fairly common to hear: “the time has come for a new vision for Palestine/Israel.” It is hard to refute the reality of a dead-end implied in this expression, but must a dead-end always lead us to a new vision? As Hanan Ashrawi has previously stated, new forms of talks, dialogue, and inventiveness are not what was missing in the endless peace talks between Israelis and Palestinians.

After 65 years of “peace talks” – they didn’t start with the Oslo accords, but way back in 1949 – we should question the very relevance of the procedures of peace. A peace treaty is usually called for in a situation of war between two existing states. In the case of Palestine since 1949, peace talks were a means for imposing partition, which was rejected by the majority of the population in Palestine in 1947; they were a way to bypass that rejection and implement partition through violence. In 1948-49, 750,000 Palestinians were expelled, the country was destroyed and its face transmuted by the new state; but full partition was not achieved. Ever since, maintaining the fantasy of separation has required the use of more and more violent solutions to the problems entailed in partial partition. Peace talks are a means of ruling that for the last 65 years have kept Palestinians and Jews haunted by the same question that colonialism lethally injected into the Middle East: for or against partition; one or two states. The major difference between then – prior to 1947 – and now is the excessive violence that was exercised in order to achieve what was doomed from inception as opposed by the majority of the concerned population – namely partitioning.

Read more: One state: Stop the hysteria and start thinking

Therefore, instead of inventing more new solutions, forms, procedures, steps, tools, terms, maps and documents to bypass the root of the problem, the time has come to address it. The root of the problem is the Palestinians’ uprooting from their land in 1948. The root of the problem is the fact that they were not allowed to return to their homes. The root of the problem was imposing the outcome of this violence as a fait accompli, as a new board game where Israeli-Jews incarnate sovereignty, and can therefore set the rules. A board game where Palestinians can – and should – be continuously dispossessed and beg for their rights, as if Israelis could have their rights while Palestinians are dispossessed of them.

Is a new vision really necessary in order to imagine an egalitarian civil contract among the populations of this non-partitionable territorial unit? Since the creation of the State of Israel, it has become impossible to imagine the future. If and when efforts to change the situation were made, they took the form of “solutions” to “problems,” imposed top-down and usually produced by the same – military-security – system. The ideology of imposed “solutions” generated the Nakba as a by-product of an effort to “solve” another “problem”: how to reduce the inadmissible gap between the minority’s desire for Jewish sovereignty and Palestine’s mixed population.

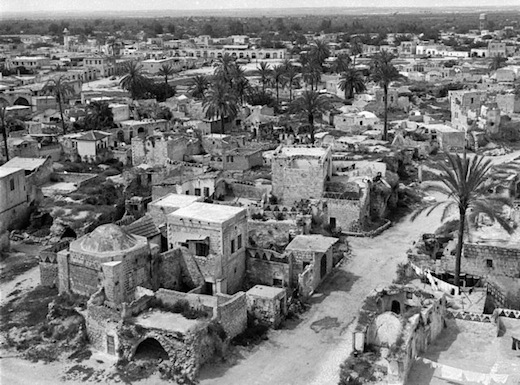

Instead of more “solutions,” the time has come to acknowledge the monumentality of the Nakba: without fully addressing it, all visions for Israel-Palestine are doomed to fail. The time has come to acknowledge the Nakba as a catastrophe not only for Palestinians but also for the Jewish people – the catastrophe of becoming perpetrators, of becoming responsible for expelling the majority of the population living in Palestine in 1948 and for the systematic destruction of one of the nicest places on earth. One should be trained as an art historian or archivist in order to take advantage of the beauty here, as so little remains.

What is needed now is not a new vision but an old one; one envisioned by people who lived in Palestine before the curse of partition and who were able to foresee partition as a horror to avoid*. What is needed is the renewal of a civil contract of equality among all those affected by the Nakba, victims and perpetrators alike. A renewed civil contract is needed to allow Palestinians to gain their freedom, and this same contract will allow Israelis to gain freedom as well: the freedom of not being perpetrators, the freedom to be governed equally. Born as an Israeli citizen, one is socialized not to know about the Nakba. One has to undergo a long journey to be able to denaturalize the numerous traces, testimonies, images and claims of the Nakba that surround people who live in what once used to be Palestine. Only once these traces and debris are endowed with meaning will common interest tie Palestinians and Jews together to make their common past the basis for the renewal of a civil contract. And it is only within that contract that atrocities like expelling people from their houses and dispossessing them will never recur.

We have inherited the crimes of our parents’ generation, but we can – and ought to – refuse to further inherit the crime of perpetuating the Nakba. We perpetuate the crime every time we refuse to recognize the Palestinians as part of our body politic, as having equal part in the land and its government. The mandate of partition is over. The time has come to explore the options that were imagined when partition was only a threat and not yet a regime under which civil options were violently silenced. The libraries and archives are full of amazing political prose, written by Arabs and Jews, which could be recalled and revitalized. We should revive them because in their language one can find exactly what we have lost – the possibility of speaking naturally – and without sounding as if we claim the impossible – on the basis of a common ground, the ground of sharing the same land.

The crimes of the past cannot be undone, but their perpetuation can be stopped. Only from an unconditional, common civil contract, can those crimes be healed and compensated for. When this happens, sovereignty will be actualized as the people’s sovereignty, wherein the people are the sovereign.

*Among them one should retrieve from oblivion names such as Albert Horani, Norman Bentwitch, Harold Laski, Yehuda Magnes, and many many others.

Related:

Two state vs. one state debate is a waste of time, political energy

Why we can’t stop having the one- or two-state debate

How a Jewish Agency fellow becomes a one-state activist

Why it’s time to discuss the one-state solution