The debate in Israel around Amnesty’s recent “apartheid report,” such as there was one, consisted of three familiar appraisals of its contents: some dismissed it as an antisemitic blood libel; some shrugged it off as a statement of the obvious; and others pondered whether this was a development with concrete legal ramifications. What was and continues to be missing in the meantime is a frank discussion of our responsibility as Jewish Israelis not only for the past, but for the future of this country.

Published in early February, Amnesty International’s report is systematic and comprehensive, but does not offer significant new information, and its recommendations are limited. The evidence for Israel’s violations of international law listed in the report will come as little surprise to any Israeli who has ever listened to the news — let alone left-wing activists. Its importance and practical significance lie rather in its two meta-arguments. The first is that the Israeli variant of apartheid is not limited to the occupied territories or to any particular part of the Palestinian population, but is inherent to the very partition of the territory and population into units with different legal statuses.

The second meta-argument is that denying the Palestinian refugees’ right to return to the land and homes from which they were displaced in 1948 is the central mechanism of that policy principle.

The decision to refer to the Palestinian refugees in a report on Israel’s present responsibility and steps required for a future of justice, equality, and reconciliation is a unique one, which breaks through the narrow bounds of Jewish-Israeli political discourse. Within that discourse, the right of return is usually addressed in terms originating from the Israel propaganda machine: from “there was a war and they lost it,” to the claim that the return of Palestinian refugees is synonymous with the end of Jewish existence in Israel. Reading the “apartheid report” offers an opportunity to realize that the opposite is true: it is preventing refugee return that constitutes an ongoing existential threat.

1948: Opening move

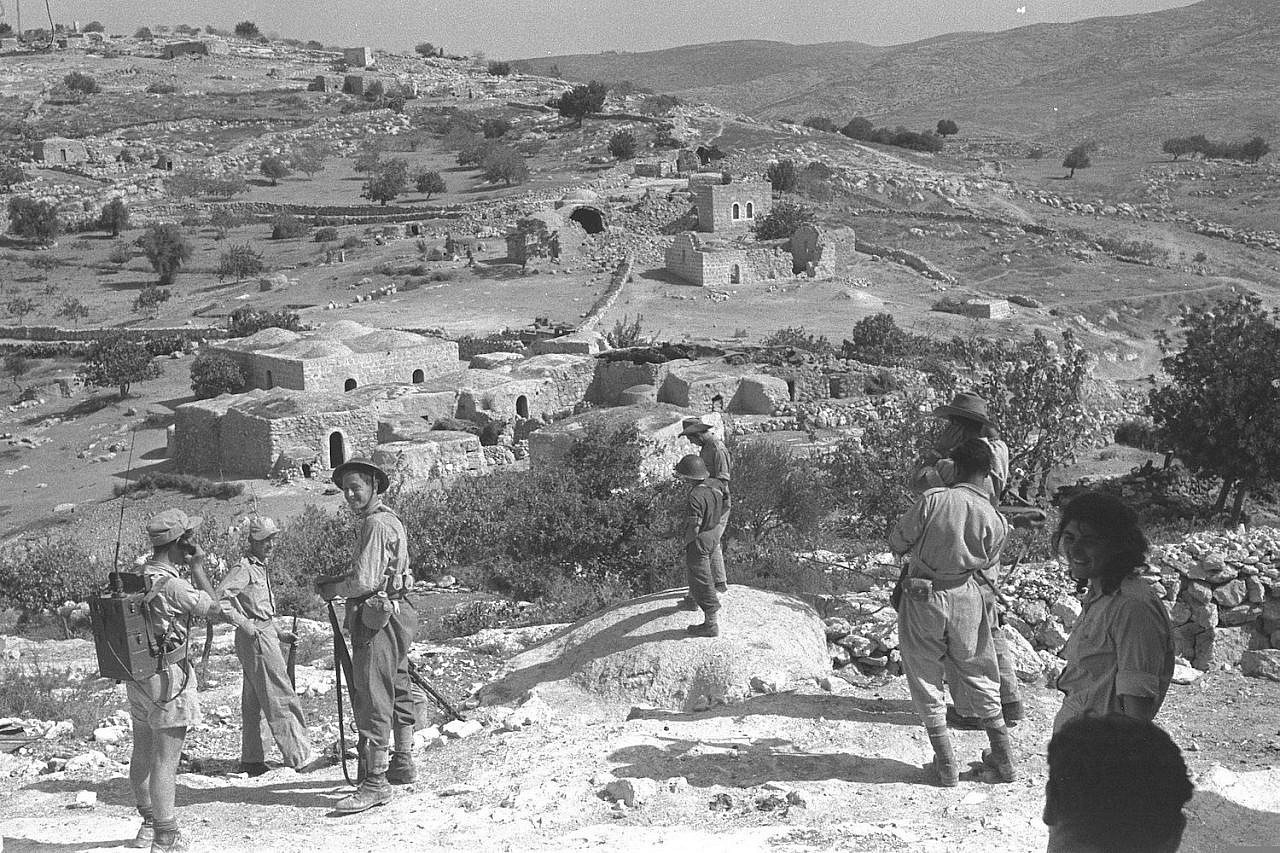

The report states that Israel’s apartheid policy has been implemented explicitly and consistently from its very first day. One of its main arguments is that before the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, conditions were ripe for establishing Jewish demographic superiority and for maximizing Jewish control of lands and natural resources. The numbers behind the 1948 war clarify this point well: until that year, the Palestinians represented some 70 percent of the country’s inhabitants, holding approximately 90 percent of its land, whereas the Jews were less than 30 percent of the population and owned less than seven percent of the land. Two steps taken by the fledgling state enabled it to completely reverse the situation: the decision made in 1948 to prevent refugee return and the 1950 Absentees’ Property Law.[1]

In May 1948, as the war was raging, a special committee was established in order to examine how to turn the Palestinian’s flight “into an accomplished fact.”[2] The committee recommended to the Israeli leadership to destroy Palestinian locales, prevent land cultivation, settle Jews in the depopulated villages, pass laws to freeze the current situation, and invest in propaganda.[3] The recommendations were implemented religiously: already at a cabinet meeting of June 16, it was announced that Israel would not let any refugees return; military units were sent to blow up villages or set them on fire (601 villages were destroyed, most of them by the first half of 1949); new Jewish immigrants were housed in depopulated Palestinian homes (350 of the 370 new Jewish settlements established in 1948-1953 were located on refugee lands); and Palestinians who tried to return to salvage some of their property, to forage for food or to reunite with families left behind were summarily shot.[4]

The prevention of return did not end with the 1949 armistice. It continues to this day, in violation of international law, without any defense-related justification, and often even without demographic justification.[5] Moreover, the Absentees’ Property Law authorized the state to hold property belonging to anyone absent during the country’s first census in November 1948, whether present within the state’s borders or not. This enabled Israel to expropriate most of the country’s arable lands, tens of thousands of housing units and commercial buildings, vehicles and agricultural and industrial equipment, bank accounts, furniture and carpets, about a million farm animals, and so on.

Even though the law was intended to be temporary, and even though the Custodian of Absentee Property was prevented from reselling expropriated assets, additional laws and regulations were passed over the years to enable Israel to seize private Palestinian land on both sides of the Green Line and designate them for military use, for the use of Jewish settlers, or for parks and facilities intended, in almost all cases, for the benefit and well-being of Israel’s Jewish citizens.

Deepening control, suppressing resistance

Spatial and demographic advantage for the Jewish population has been deepened and retained ever since by splitting the Palestinians into units of distinct legal status: refugees in non-Arab countries, refugees in Arab countries, the Palestinians who remained within the State of Israel, including the internally displaced, the residents of East Jerusalem, the inhabitants of the “unrecognized” Bedouin villages in the Naqab/Negev, and the inhabitants of the occupied West Bank and the besieged Gaza Strip. As Amnesty notes[6]:

The very existence of these separate legal regimes […] is one of the main tools through which Israel fragments Palestinians and enforces its system of oppression and domination, and serves, as noted by the UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA), “[…] to suppress any form of sustained dissent against the system they have created.[7]

The report enumerates the types of oppression exercised under each legal regime, such as mass arrests, torture, land grabs, massacres, movement restrictions, denial of access to resources, disruption of family life, and so on. This has been done before. But the paramount importance is the report’s warning that opposition to the specific characteristics of oppression, without reference to the very fact of fragmentation, in itself serves the same oppressive system. For example, focusing solely on Israeli crimes in the occupied territories covers up the additional violations of international law regarding the refugees, while at the same time covering up the discrimination of the Palestinians who remained behind the Green Line and in East Jerusalem, or at most misrepresenting them as part of the discourse on minority rights in a liberal society.[8]

The authors of the report argue that the apartheid conceptual framework enables a coherent understanding of the metalogic of the various forms of oppression: the intent to retain a system of control, while establishing and preserving Jewish hegemony. This is precisely the meaning of what Palestinians have longed termed the “ongoing Nakba.” Moreover, apartheid is also a term grounded in international law, thus entailing conventional sanctions. The reference to the objective of control, rather than just the means, also makes it clear that the problem is not — and has never been — reducible to a “group of extremists.” The responsibility for the problem lies with all state and quasi-state institutes, with the World Zionist Organization, with all state government regardless of party affiliation, with the judiciary branch, with the Custodian of Absentee Property, with the Jewish National Fund.

The key to the problem

Preventing the refugees from returning, from 1948 through 1967 and to this day, is presented in the report as a major mechanism of the Israeli version of apartheid. The right of return is mentioned in the report more than 50 times, guiding its legal, historical, and spatial analysis.

In legal terms, one implication of the denial of return is that Israeli control is not limited to Israel’s borders, but is directed also at the Palestinians who have been uprooted over the years, given that their absence is essential for maintaining a Jewish majority.[9] No less important is the implication that apartheid will necessarily prevail so long as the refugees are prevented from returning.[10]

Historically, expulsion and prevention of return represent the explicit logic of Israel’s moves, even after 1948. In the immediate aftermath of the war, Israel imposed a military government on 85 percent of the Palestinians who remained within its territory, despite their formal citizenship status. For no less than 18 years, Israel denied them basic rights such as the right to property, freedom of speech, and freedom of movement, while confiscating their lands and other properties and establishing an intricate system of monitoring and supervision that restricted their ability to organize politically and shape their destiny. Based on official documents, the report states that the military government was annulled in 1966 only once there was sufficient certainty that the refugees were no longer able to return, mainly after nearly all Palestinian villages were destroyed and afforested.[11]

Even the occupation of the West Bank began the very next year, the re-imposition of military rule on the other side of the Green Line cannot be understood separately from Israel’s depopulation policy. In the course of the 1967 war, more than 350,000 Palestinians were uprooted, half of them refugees from the 1948 war.[12] Some were forced into convoys heading toward Jordan, including the thousands from the villages of Imwas, Yalu and Beit Nuba.[13] Others were forced to flee in various ways, such as massive bombings and demolitions, as in the Iqbat Jaber Refugee Camp south of Jericho, which was the largest camp in the Middle East, until 90 percent of its inhabitants were deported to Jordan.[14] The refugees from 1967 are also denied the rights granted by international law.

An opportunity for Jewish society

These are all arguments made by Palestinian society for over seven decades, and it is a positive step that the international community has begun to lend them credence, both in principle and through research and the dissemination of information.

But what about Jewish society in Israel? Amnesty International’s report represents yet another opportunity for this society, or at least those who believe in humanism and equality, to acknowledge the centrality of Palestinian refugeehood in the story of Zionist existence in Israel. To do so, however, would mean they will have to relinquish several persistent myths:

“It was an unintended consequence.” In fact, from its very beginnings, Zionist settlement in Israel strove to gain as much territory for exclusive Jewish benefit. Even if not all Zionist thinkers and decision-makers agreed with that interpretation of Zionism, this was the ideology that was effectively implemented. There is evidence that as many as 57 Palestinian villages were uprooted before 1948, as well as explanations undermining the claim that the land from which they were removed was bought through legal means.

“They started it.” 1948 is not the starting point but the zenith in a process of systematic depopulation. Even the narrative suggesting that the Zionist leadership accepted the 1947 UN Partition Plan, thousands of Jews danced in the streets of Tel Aviv, and the Arabs started the war is mendacious propaganda. Historical sources show that the Zionist leadership had absolutely no intention of settling for the territory designated to the Jewish state under various partition plans. Both Israeli Prime Minister David Ben Gurion and other Zionist leaders stated in no uncertain terms that agreeing to the plan is a diplomatic move designed to expedite the British evacuation and facilitate the takeover of as much territory as possible.[15]

Even the balance of power on the ground fails to reflect a situation of Jewish defensive against an Arab offensive, as the “few against many” or “David vs. Goliath” narrative has struggled to prove. By late 1947, the Jewish community in Palestine had an organized military force of some 40,000 fighters, facing a mere 10,000 mostly untrained and poorly organized Palestinian fighters and volunteers from Arab countries, most of them without military experience. Even in May 1948, when the war expanded to include Arab armies, Israel had the two-fold advantage of greater resources and better quality arms.[16]

“What can you do? War is a terrible thing.” If only for sheer scale, the deportation and dispossession of the Palestinians cannot be written off as a necessary part of the fighting. Some 750,000 women and men became refugees in this war, and their property was seized. About half were forced to flee or were expelled before the Arab armies joined the war.[17] Legally speaking, the distinction between “flight” and “deportation” is also bogus: civilians tend to flee wars and other disasters, seeking temporary refuge with the intent of returning home after the fire subsides, and international law grants them that right. Such cases did indeed take place during the 1948 war, alongside documented instances of forced uprooting.[18] In both cases, the prevention of return is inexcusable and is completely unrelated to the question of the responsibility for the outbreak of the war.

“That’s the way it is.” Palestinian refugeehood is often associated with other historical cases of ethnic cleansing that serve to justify it. No deportation is ever justified, and the crimes of others will never justify one’s own. Jews were also uprooted and deported with great cruelty, and this is one of the reasons the world recognized their right for a sovereign state. In many cases (including the present-day heirs of medieval Spain and Nazi Germany), the criminal’s descendants have apologized after the fact, paid reparations, erected monuments, developed curricula, and enabled second- and third-generation victims to obtain citizenship and reclaim property. None of these steps was carried out in the Palestinian context, and moreover, the oppression continues apace.

“Let bygones be bygones.” The belief that the outcome of the 1948 war may be separated from everything that happened before and after it, and that Israel can simply “move on,” is based on Jewish-Zionist supremacy that has no political, legal, or moral justification. While Jewish demographic advantage was ensured by 1948, Israel’s ethnic cleansing policy was not limited to wartime.[19] Second, such an approach completely erases the Palestinians: the catastrophe is far from over for Palestinians who are denied even the right to visit the ruins of their village, for split families unable to rejoice or mourn together, for a resident of Jaffa whose sister is besieged in Gaza or a Hebronite prevented from wedding his Haifa sweetheart.

The time has come to talk about return

What the Amnesty International report states, as the Palestinians always have, is that any solution that maintains the system of split rights and does not protect the freedoms of the entire Palestinian people — in the diaspora, in Israel, in the West Bank, in East Jerusalem and in Gaza — will not offer a sustainable solution for the ongoing injustice. “Dismantling this cruel system of apartheid is essential for the millions of Palestinians who continue to live in Israel and the occupied territories, as well as for the return of Palestinian refugees […] so that they can enjoy their human rights free from discrimination.”[20] The dismantling of the Jewish supremacy regime is also essential for millions of Jews in and outside Israel — not because Amnesty says so, but because doing so will lead to a better future for us all.

History shows that societies founded on a supremacist and exclusivist ideology are necessarily racist and militarist; this is indeed the direction where Israeli society is heading. Recognizing the rights of the refugees as grounded in international law is a prerequisite for ending the Jewish supremacy regime, and hence for reconciliation, democracy, and equality. Such recognition will enable establishing a fair immigration policy that will benefit society, culture and the economy, and even promote distributive justice within Jewish society in Israel.

Realizing the right of return will require Jews to give up on their privileges; this much is true. But what is the cost of retaining a “Jewish state?” So far, despite justifying its legitimacy through promises of pluralism and appeals to universal rights like the right to self-determination, this state has adhered to a narrow, rigid interpretation of Jewish law, creating inequalities and exclusions that contradict any notion of liberalism or universalism (exemplified most clearly in marriage law and immigration policy). The Jewish definition of the state of Israel harms non-Jews first and foremost, but exacts a considerable toll also from many Jews — especially black, LGBTQ, and women who cannot obtain a divorce (Agunot). It harms Jewish life itself, by harnessing it both to the Zionist project and Ashkenazi orthodox law, thus impeding the independent and spontaneous development of tradition as occurred and still occurs in the diaspora. In contrast to life under community-based institutions, Jews in Israel are compelled to finance and be subjected to the Rabbinate’s monopoly over religious services.

Additionally, the constant fear of the “demographic threat” continues to justify the allocation of resources to military needs and illegal settlements in the occupied territories rather than public health, housing, and education. The need to justify the constant anxiety and defensiveness instructs, in turn, a deeply racist and militarist education system. The future promised by this path is not the future I want. There is nothing brave about seeking total security out of constant fear of a supposedly existential threat. We can and we must break free of the concept that Jewish liberation must come at the expense of others. We must begin to take responsibility for our future.

Whoever is committed to justice and equality, whoever is opposed to racism, whoever simply does not want to take part in a crime against humanity, and whoever simply wants things to be better here must dare to think and talk seriously about return. A good first step would be to listen to the refugees themselves and to Palestinian civil society organizations, and find out that return is not tantamount to deporting the Jews from this country.[21] Al-Awda, The Palestine Right to Return Coalition, which is the broadest non-partisan democratic global association advocating for the implementation of the right of return, clearly notes that “Palestinian refugees broadly accept that exercising their right to return would not be based on the eviction of Jewish citizens but on the principles of equality and human rights.” Similarly, BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, explains:

What happened in 1948 is history. There’s no going back. The right of return, however, is not about going back in time. Return is much more about the future. It is really about starting to live, answering the deep sense of belonging to the land from which refugees were torn decades ago, and about building relations between Palestinians and Jews that are based on justice and equality (emphasis mine).

Will this stance change once the balance of power has shifted? Perhaps. Some define homophobia as “the fear that gay men will treat you the way you treat women.” Return-phobia would be the fear that Palestinian refugees will treat you the way Zionism treated them. I choose not to live in fear, but rather have faith in people who believe in human rights and equality. I choose to trust refugees, such as Isma’il Abu Hashash, uprooted from Iraq al-Manshiyah who resides today in the West Bank, who says:

We must not repeat the Israelis’ mistakes and condition our existence in our land on the non-existence of the people now living there. The Israelis, or the Jews, thought that they could live in Palestine only if the other could not. That’s not what we believe. We see the right of return as a demand for an individual and a collective right to the land from which we were expelled. We don’t want to tell them to leave, nor do we want to divide their country.

You can also hear from Jews who support return about why they believe it would also benefit the Jews of this country. You will find that as much as the issue of return is highly controversial and emotional in Israeli society, a lot has been written about it over the past years.[22] Next we can move on to more pragmatic discussions. Salman Abu Sitta is an exiled Palestinian geographer who has devoted his life to analyzing the practicalities of return. His studies indicate, among other things, that the great majority of land to which the refugees seek to return is currently uninhabited. The Cape Town Document, a vision for return formulated jointly by Zochrot, an Israeli organization that promotes the right of return, and Badil, a Palestinian organization for refugee rights, offers a legal outline for the realization of return. There is also much information on refugees returning to their home countries around the world and on the challenges and opportunities posed by voluntary return for example in the October 2019 issue of Forced Migration Review.

If there is one thing Jewish Israelis can learn from the Amnesty report, it is that the attempt to disconnect the events of 1948 from Palestinian existence in 2022 is artificial and cynical, and that the call to acknowledge that is not a request for empathy but a demand for redress. Because the Nakba is a deliberate and ongoing effort to erase the Palestinian people from this land, in our name and with our participation. It is important to oppose house demolitions and to accompany Palestinian shepherds in the Jordan Valley. It is important to demand water and electricity for the subjects of occupation, to monitor settlement construction in the West Bank, and to talk about peace. However, realizing the refugees’ right to return is the only move that honestly acknowledges the fundamental injustice that has created the relations of oppression between Jews and Palestinians, which continue to this day. It is the only move that attends to the true wishes of the victims, and that has a true aspect of justice and healing. It is scary, but also exciting. It is complicated, and it will take time. This is exactly why we should start taking it seriously.

_______________________

[1] All references to the Amnesty report are to the complete English version.

[2] The prevention of return is discussed, among other things, on pages 14-15, 61, 64, 72, 75, 81, and 93-94; for the appropriation of Palestinian assets through the Absentees’ Property Law and the 1953 Land Acquisition Law, see among other things pp. 22-23, 114-116, 119-121, 124.

[3] Memorandum by Y. Weitz, E. Sasson, and E. Danin to Ben-Gurion, “Retroactive Transfer: A Scheme for Resolving the Arab Question in the State of Israel,” June 5, 1948, quoted in Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 314-316.

[4] Noga Kadman, “Erased from Space and Consciousness: Israel and the Depopulated Palestinian Villages of 1948” (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015), Introduction; Oren Yiftachel and Alexandre (Sandy) Kedar, “On Power and Land: The Israeli Land Regime,” Theory and Criticism 16 (2000): 77 (Hebrew)

[5] Demographic considerations do not explain steps taken to prevent the return of internally displaced persons, such as the inhabitants of Saffuriyya or Kafr Bir’im, most of whom still live in Israeli territory.

[6] Pp. 74-81.

[7] P. 17.

[8] E.g. pp. 62, 75.

[9] Pp. 62, 81.

[10] Pp. 33, 47, 93-94, 220, 259-260, 276.

[11] Pp. 105-106.

[12] Pp. 41, 76-77, 81.

[13] “They asked to return to the village, and said we had better kill them […]. We didn’t allow them to go to the village to take their belongings, because the order was that they were not to see how their village was being torn down.” Testimony of late Israeli author Amos Keinan, who served in the war, in “Report on Village Demolition and Refugee Deportation, June 10, 1967,” quoted in Sedeq 2 (2007): 96-97 (Hebrew).

[14] Nur Masalha, The Politics of Denial: Israel and the Palestinian Refugee Problem (London: Pluto Press, 2003), 203-205.

[15] As early as in March 1937, Zionist leader and future President of Israel Chaim Weizmann told the British High Commissioner of Palestine: “Even if we suffer setbacks from time to time, we are bound to inherit the entire country in the end; unless the country is torn in two and a border is drawn to our expansion […]. Even if the partition plan is approved, we are bound to ultimately spread over the entire country […]. This is nothing but an arrangement for the next 25-30 years.” Moshe Sharett, Yoman Medini, Vol. 2, p. 67 (Hebrew), cited in: Alexander B. Downes, “Targeting Civilians in War” (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011), p. 187.

[16] Benny Morris, “1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 81-93, pp. 197-207.

[17] Internal Israeli intelligence documents confirm that “the displacement of some 70% of the Arabs during this time should be attributed to military operations carried out by Jewish forces, while orders given by Arab leaders impacted the displacement of only 5%.”

[18] The following are a few out of many examples. Jewish soldier Amnon Neumann testified: “We surrounded the village from all directions, started shooting in the air and everyone began screaming, and we expelled them.” The operational orders of Plan D (March 1948) call for “cleansing” and “destroying” villages. The inhabitants of Ramle and Lydd were given leaflets ordering them to go out on foot, and Israeli troops shot over their heads until the refugee convoys arrived in Jordanian territory. In Majdal, the transfer was carried out using military trucks.

[19] In 1950, 2,500 Palestinians who remained in the town of Majdal (today Ashkelon) were deported; by 1956, more than 20,000 Palestinian Bedouins who remained in the Negev were forced out; and in 1956 alone some 5,000 Palestinians were evicted from demilitarized zones in northern Israel. As mentioned, the 1967 war had its share of expulsions as well, and the phenomenon continues to this day in both Israel and the West Bank. Also in ongoing use are various methods of coercive emigration.

[20] P. 33.

[21] It is hard to choose from the various publications by Palestinians on return. Here is a very limited selection: You can read a few short quotes by refugees talking about return; read Abir Kopty’s piece Without Return, Palestine Will Not Be Free, 15.5.2013; watch Firas Khouri’s short film “Three Returning Bouquets” and listen to how teenagers describe their yearning for return; watch Internally displaced Palestinians plan their return; imagine, together with Umar al-Ghubari and others, possible futures of return and share d living, as related in the book “Awda” wander around the sites envisioned by the Al-Awda coalition of return and the BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights.

[22] English: Peter Beinart, A Jewish case for Palestinian refugee return, The Guardian, 18.5.2021; Alma Biblash, Who’s afraid of the right of return?, +972 Magazine, 15.5.2014; Tom Pessah, Yes, the right of return is feasible. Here’s how, +972 Magazine, 7.11.2017; Moran Barir, I have a dream — to see the Palestinian refugees return, 2012; Henriette Chacar, The Jewish Israelis helping make Palestinian return a reality, +972 Magazine, 29.5.2020. Hebrew: Alma Biblash, It’s Time to Talk about Return as a Practical Option, Local Call, May 5, 2014; Rachel Beit Arie, We Have Grown Used to Viewing the Return as a Threat Rather than a Hope, Local Call, December 2, 2018; Tom Pessah, Time for a Serious Discussion on the Right of Return, Haokets, November 5, 2017; Tom Pessah, The Right of Return: Not What You Thought, Sicha Mekomit, April 18, 2018; Joint Meeting on the Ruins of the Village Mighar, Israel Social TV, November 7, 2017; and a series of Israel Social TV items on the right of return, interviewing, among others, Avi-Ram Tzoreff, Jessica Nevo, Yossef(a) Mekyton, and Moran Barir.

This article was first published in Hebrew on Haokets and translated into English by Ami Asher. Read it here.