On a recent summer night, equipped with a large flatbed truck and jeeps, Israeli soldiers entered the Palestinian village of Taquu near occupied Bethlehem to remove a Byzantine baptismal stone font. A Palestinian man captured the scene with his mobile phone, hand unsteady as he documented the military vehicles from above.

The video went viral on Twitter, and a debate ensued around whether the stone font “belonged” in the area where Israeli forces had lifted it. Some argued that the font was simply being returned to Israel, after Palestinians moved it from the Israeli settlement of Tekoa some 20 years ago.

Much of the debate over where the font belongs not only fails to acknowledge the illegality of settlements in the West Bank, but tends to ignore another major issue: Israel’s weaponization and militarization of archaeology between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.

Though the military looting in Taquu reflects the kind of unabashed show of power that is rarely caught on tape, this systematic expropriation is not invisible to the Palestinian eye. And it is certainly not a recent phenomenon: multiple settler-colonial authorities that have controlled Palestinians over the last century have weaponized archaeology in some form. Today, Israel sponsors and promotes archaeological initiatives in Palestine with the sole purpose of linking only the Jewish narrative to our land, rather than embracing its entangled complexities.

Archaeologists look for answers in the soil — for remnants of previous lives, and for fragments that can reveal ancient history. Good archaeologists dig first, and construct a narrative based on the clues they find in the ground. The problem arises when they begin digging with a preconceived idea of what they are looking for.

As early as 1908, Western institutions such as Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania began excavating Palestinian ground with a subjective Judeo-Christian lens. Gottlieb Schumacher, who led the Harvard excavations of the Palestinian village of Sebastia, was a practicing Templer (German settlers who believed that living in Palestine would hasten the Second Coming of Christ). The diggings were funded by Zionists such as Jacob Henry Schiff, who was a Jewish community leader in New York and a well-known Wall Street banker. Schiff entirely changed archaeologists’ perception of Palestine, and is credited for the rise of biblical archaeology in the United States, an academic discipline that uses excavations in Palestine to prove the historical authenticity of religious texts.

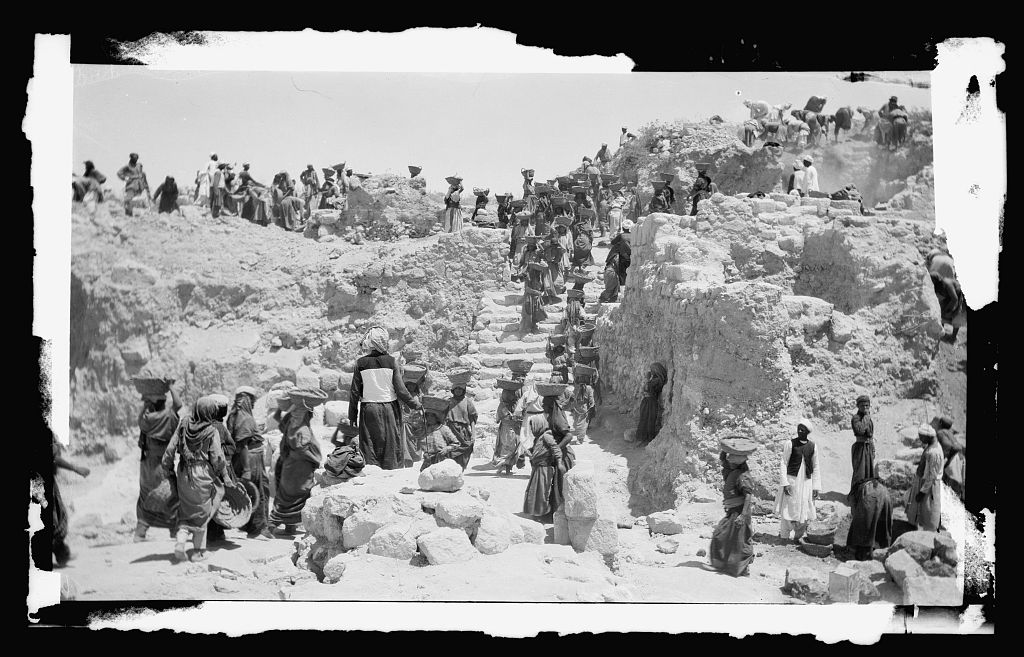

That history is not only documented in books and academic journals, but is also embedded within the memories of Palestinian grandparents, who worked as cheap labor excavating archaeological sites for decades.

Two months after Israel’s establishment in 1948, the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums (IDAM), a precursor of the Israel Antiquities Authority, was founded under the Education Ministry. As early as 1950, guards who held the status of police officers were placed at archaeological sites across the country. After the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel immediately enacted an antiquities law in Jerusalem, giving IDAM authority to excavate within the Old City as well as its surroundings; the number of excavations within the city ballooned from 60 before 1967 to 150. In 1995, under the second Oslo agreement, Israel was granted authority over 7,000 archaeological sites in the West Bank, of which 53 percent are in Area C, where Israel has full administrative and security control.

Given Israel’s systematic archaeological plunder, the soldiers captured on the phone footage from Taquu cannot be solely complicit in the font’s removal. Hananya Hizmi, the head of the Archaeology Department of the Civil Administration, the arm of Israel’s military government in the occupied West Bank, said he was thrilled that his team succeeded in “returning” the Byzantine font; they had been searching for it for years, he explained, and will continue working toward preventing “antiquities thieves from looting the history of the region.”

This military archaeologist — which, as a profession, should simply not exist — was celebrated as a heroic figure in a 2018 exhibition at the Bible Lands Museum in Jerusalem. Entitled “Finds Gone Astray,” the exhibition essentially glorified the Israeli military’s role in confiscating archaeological artifacts from the West Bank. According to the museum’s director, roughly 40,000 artifacts were “recovered” by the Israeli authorities.

This stark number of artifacts should raise major warning flags — especially during a time of increased black market activity, after the wars in Iraq and Syria. It is unclear where the artifacts were retrieved from, and not knowing their provenance makes it challenging to date them with credibility and prove their authenticity. This act of displacement gives museums, collectors, and cultural ministries the power to reframe theft as recovery and to loot houses as prestigious institutions.

Locals from villages across Palestine told me they had witnessed Israeli military vehicles looting artifacts in the middle of the night multiple times over the past several years, as they did in Taquu. Parallel to this large-scale looting, Israeli authorities would break into homes in Al-Jib near Jerusalem and arrest young men for having a few pottery shards, according to one resident. There are also more settlers visiting the village than in the past, with protection from the Israeli army, another resident added.

In Sebastia this year, the nearby Israeli settlers of Shavei Shomron burned down the olive groves surrounding the archaeological site, and intentionally polluted the agricultural land with wastewater from settlement factories.

Wadi Hilweh in Jerusalem’s Silwan neighborhood, now called The City of David, is in critical danger of being wholly cleansed of Palestinians and gentrified as an exclusively Jewish tourist attraction, despite the presence of Canaanite and Iron Age remains. News broke last week that Elad, the Israeli settler group operating the City of David as well as other archaeological sites in Israel, received $100 million in funding from Roman Abramovich, the Israeli-Russian billionaire and owner of the English soccer club Chelsea.

In many of these sites, monuments such as the amphitheater and Roman fora are used as stages and backdrops for performances that perpetuate Zionist propaganda. Actors dress in ancient costumes and recite the Torah while referring to the biblical names of the archaeological sites. These performances are largely catered to a young audience, a future generation of Zionist settlers.

The Civil Administration’s displacement and looting of archaeological artifacts on occupied territory, which is prohibited under the Hague Convention, raises questions about the fate of other archaeological sites in Areas B and C of the West Bank. The Civil Administration has recently increased its demolition orders in Palestinian villages near these areas, and historically, it has denied Palestinians access to their agricultural properties and the right to build or develop any infrastructure, all of which has made the preservation of the sites difficult.

But in the face of these challenges, a younger generation of highly active and resilient Palestinians is rising. They are taking on this struggle by reclaiming their history and spreading awareness and knowledge about Israel’s misuse of archaeology, as well as drawing attention to the critical conditions of these sites and their artifacts.

For Palestinians, these historical objects are evocative. They act as vessels carrying our memories and traumas. Whether it’s a Byzantine stone font or a Palestinian house key from before the Nakba, these tactile forms are not merely material objects — they are tools that we identify with and resist with, and with which we exert our disappearing existence. For Palestinians, they are emotional companions.

The baptismal font’s meaning has shifted through time and place. During the 6th century, it was a static stone used for religious rebirth and spiritual awakening; perhaps thousands of children were baptized in the holy water of its hollow belly. In today’s Bethlehem, where Byzantine hymns still travel through the city and children continue to be baptized in the ways of old, the displacement of the Taquu font is an attack against Palestinian identity at its core: a people with traditions that date back centuries. The font is a witness, as it is the evidence.