Every person has that moment in which she or he suddenly understood just how great an impact the coronavirus would have on our lives and our daily routines. For me, it happened after I returned from the yearly Purim street party in the Jewish settlement in Hebron. Whether it was because the “celebration” was smaller than usual or because the settlers there believed that COVID-19 wouldn’t strike their community, only about 100 people marched on Shuhada Street, which was off limits to Palestinians long before the pandemic struck.

On the way home, I passed through the Walajeh checkpoint that connects Bethlehem to Jerusalem. Border Police officers stationed there were wearing white protective suits, masks, and gloves. That was the moment I knew things were not going back to “normal.”

The following day, Border Police officers showed up in masks during a protest against settler violence in the Palestinian village of Beita. The officers didn’t rely on social distancing rules to keep Palestinians at a distance — they had tear gas and live fire.

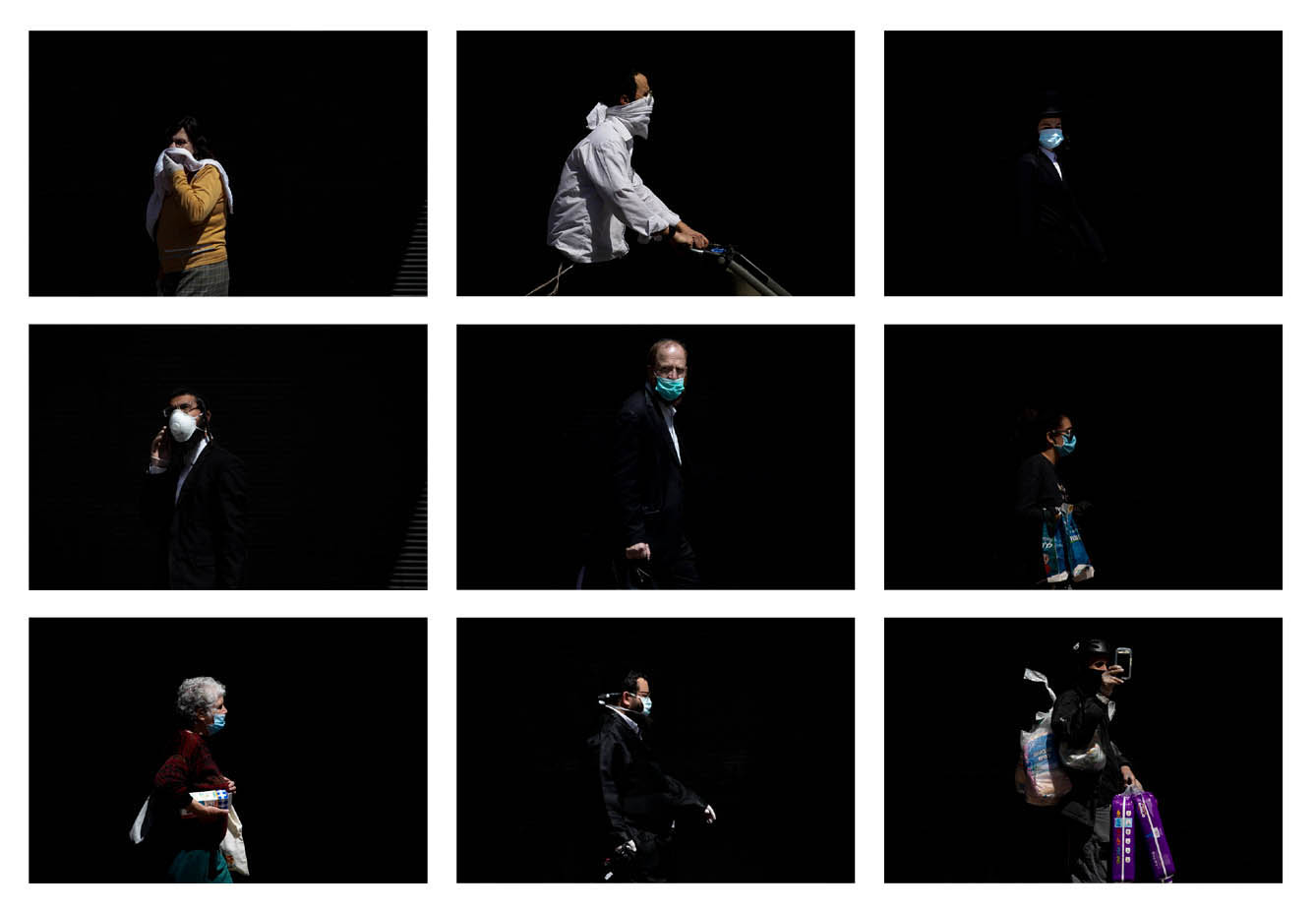

Since the start of the outbreak in Israel, while most citizens shelter in place, I, like other photographers, have been spending much of my time outside, either to take photos for my next article or to document this historic moment before we all go back to our daily routines. But with time, I recognized that there is no going back to a “routine,” even after the pandemic is behind us.

Over the past month, I’ve been photographing places, events, and things that I hadn’t photographed for years, such as street cats, markets, and sunsets. The kinds of scenes that generally don’t interest me or catch my eye.

But as the restrictions on movement in public spaces grew more severe — regardless of whether or not they are justified — every opportunity to go outside became a political act. I hoped that these kinds of photos would give people hope while stuck inside.

Over the past month, many protests have been cancelled, yet despite the restrictions and scaremongering, hundreds came to protest against the ruling Likud party’s attempt to shutter the Knesset in mid-March. The police arrested nine people.

In my travels around the country, I saw disinfection take place in public places, most often by spraying people with a mix of water and chlorine or another similar substance. From a distance, the effort looked like a publicity stunt to try and calm the public. That was until I saw workers from the Palestinian Health Ministry spraying Palestinian laborers at the Tarqumiyah checkpoint near Hebron.

The procedure was a reminder that Israel has completely abdicated its responsibility for testing Palestinian laborers for COVID-19 when they enter and leave Israel. The Palestinian Authority has built makeshift checkpoints for testing adjacent to the Israeli checkpoints.

It was also a reminder that for decades, Israel has forced Palestinian laborers to cross checkpoints between the West Bank and Israel, and that allowing them to temporarily reside in Israel was considered by the government as a security threat. But the sudden economic threat of Palestinian workers not coming to work in Israel meant they can now remain in Israel (though they can’t return to the West Bank for a month as a result).

As I traveled between Tel Aviv, the ultra-Orthodox city of Bnei Brak, Jerusalem, and the West Bank, I spoke to scores of people about how the lockdown is affecting their lives. One vendor at Tel Aviv’s Carmel Market told me that in all his years of work, even during years of suicide bombings and war, he had never seen the market shut down. At Damascus Gate in Jerusalem’s Old City, one of the Palestinian residents asked the police officers stationed there why they weren’t wearing masks. “To not frighten people,” one of them responded. “What about your weapons and uniforms? Are they not frightening?” the Palestinian answered.

On a sunny Saturday in the Tel Aviv Port, weeks before the restrictions on movement came into effect, one woman joked with me that photographing people enjoying themselves might lead Prime Minister Netanyahu to shut down the area. I saw how under the guise of the pandemic, smaller communities, particularly kibbutzim in Israel and settlements in the West Bank, decided to shut their gates in violation of the law.

One of the strangest moments was witnessing Israeli soldiers walking around Israeli cities without weapons or masks, under orders to remember that “this is not the occupied territories,” and thus they should act accordingly. Security forces walk the streets for no particular reason but to maintain their presence. In south Tel Aviv, activists who for years have been trying to expel asylum seekers from the neighborhoods began spreading lies about refugees who refuse to obey government directives, leading Netanyahu to send extra reinforcements to the area.

A week later, army trucks loaded with food and toilet paper made their way to the ultra-Orthodox city of Bnei Brak, one of the hardest-hit by the pandemic. Soldiers handing out food to needy families were sent to the city to cover for a health system that was completely unprepared for the outbreak. Residents in Bnei Brak and Jerusalem’s ultra-Orthodox neighborhood of Mea Shearim told me that they were angry that the mainstream media only cares about them during days of crisis while portraying the residents as law-breakers who are responsible for the spread of the pandemic.

On the day the city was put under lockdown and surrounded by makeshift checkpoints, one of the residents told me: “Now they are treating us like they treat the Arabs. Perhaps we’ll finally understand how they feel.”

During my days outside, I met mostly other journalists, police officers, soldiers, emergency crews, and people who dared to venture out. I did not meet the asylum seekers who have been left without livelihood or assistance from the government or the Bedouin residents from unrecognized villages that are tirelessly dealing with the crisis.

In Jaffa, I saw how the new health directives served as justification for police violence, after a young man who allegedly refused to show police his ID was charged with suspicion of breaching those directives. Although residents have stressed that police violence began long before the coronavirus pandemic, many also said that the pressure they face — the dire economic situation, and the feeling of being trapped in their homes — caused young people to take to the streets last week.

It is hard to imagine that just a month ago, we shared the public space, shook hands, ate from the same dishes and did not have to wash our hands a hundred times a day. If we judge from the history of the State of Israel, the restrictions, the heightened surveillance, and the fear of “others” will remain long after the coronavirus has disappeared from the world.