As a child, Dr. Honaida Ghanim used to play a game with her friends: they would skip from one side of the Green Line to the other in her home village of al-Marja — one minute they were Israeli Arabs, the next Palestinians.

Ghanim, now a leading Palestinian sociologist, researches this liminal experience of Palestinian citizens of Israel, who in themselves represent borders, neither here nor there. Her book on the subject, “Reinventing the Nation: Palestinian Intellectuals and Persons of Pen in Israel, 1948-2000,” is based on her doctoral dissertation.

Ghanim herself embodies this liminality, living in Ramallah and teaching at the Palestinian Forum for Israel Studies (MADAR). Well-grounded in Palestinian politics on both sides of the Green Line as well as Israeli-Jewish politics, Ghanim’s research and insights have shaped her perspective on annexation. While noting that the Green Line was erased some time ago and that annexation is already happening, she nonetheless sees an opportunity for the Palestinian struggle to return to its roots in anti-colonialism and justice.

Can Palestinians stop annexation?

“Regional and global conditions, as well as internal Palestinian divisions — between Fatah and Hamas, between Gaza and the West Bank — have created a problematic situation that does not favor the Palestinians. The international community’s will to prevent annexation is limited, while the Americans have embraced it. The intersection of all these factors means it will be very difficult to stop annexation.

“Nonetheless, an alternative long-term solution has opened up, which is based on justice rather than statehood. The unintended consequences of annexation could be to create new conditions and to restore the recognition that this conflict is tied to colonialism — the “fewer Arabs, more land” project aimed at crowding out Palestinians. But this attempt to erase the Palestinians has failed.”

It seems, on the contrary, to have been successful.

“After 1967, it would have been possible to resolve the conflict on the basis of two states for two peoples. There could have been an agreement between the Palestinians and the Israelis, with Israel receiving legitimacy as a state. This was very difficult for the Palestinians, giving up on 78 percent of their homeland. But [Israel’s] settlement logic outweighed everything else.

“This rationale’s cannibalization [of the territory] has brought the struggle back to being anti-colonial, rather than a struggle for statehood. It’s a struggle for justice and freedom.

“The Zionist project succeeded in establishing a state based on the model of an indigenous people settling [on their land]. The Palestinians saw this as a colonial project, including after ’67, but began seeking a solution based on dialogue. This developed into the two-state solution. There was opposition, but the leadership of the Palestine Liberation Organization continued down that road.

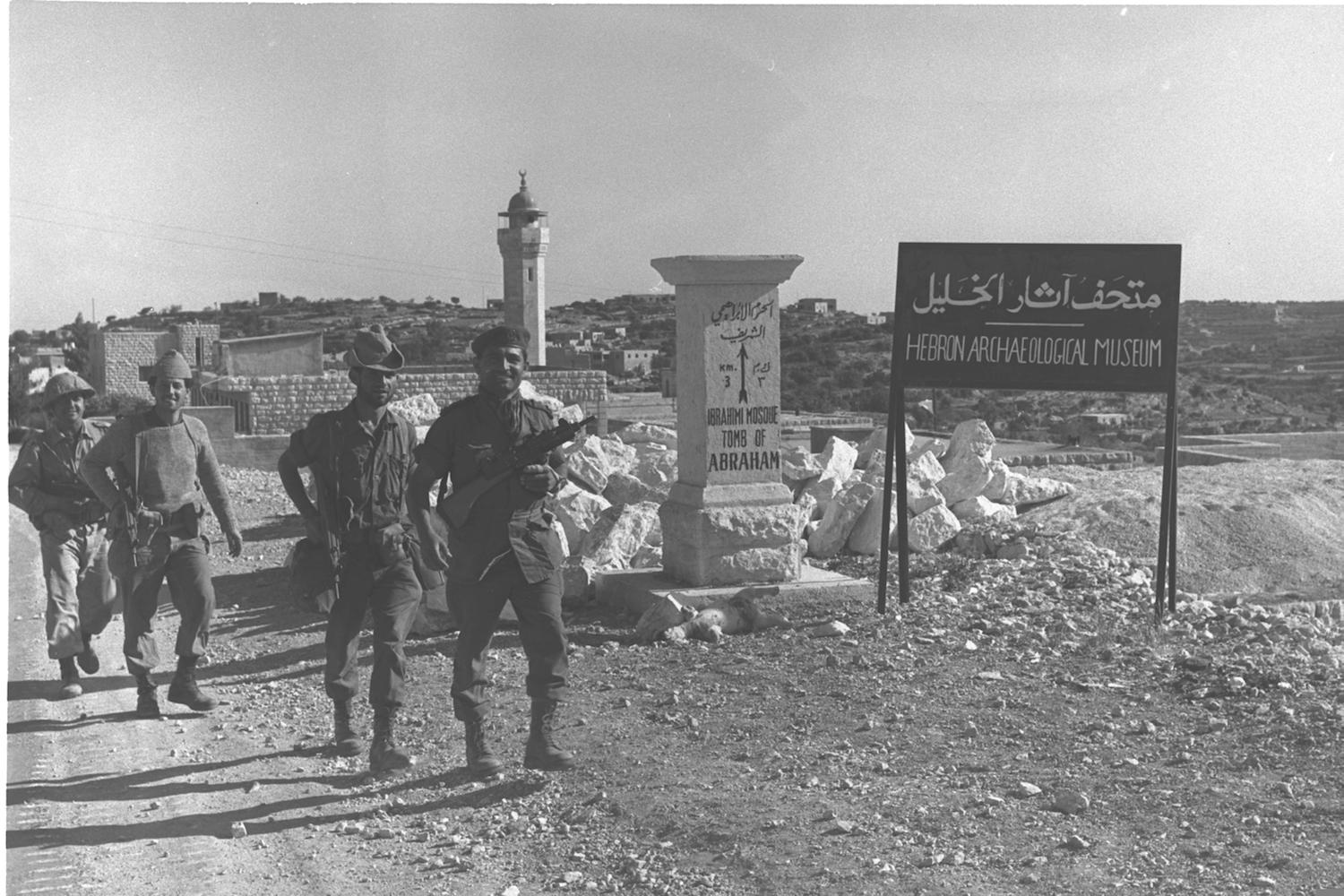

“The ’67 [Six-Day] War presented an option for whitewashing this project via an agreement with the native people. But the combination of religious, nationalist, and settler forces in Israel grew, and brought us back to 1948.

“There are a few solutions to settler colonialism. One is what Algeria did, which I know won’t happen here. Another solution is genocide, as took place in America, and another model is South Africa.

“Trump is suggesting [something like] apartheid South Africa, a settlement model in its most backward form that puts people in cages. But no one is buying it, not even the right.

“Annexation is about ‘fewer Arabs, more land.’ Land is the most important form of capital. The goal is to find an arrangement for the Arabs. Expulsion and transfer, which were possible in 1948, are no longer possible. Instead [Palestinians are being offered] autonomy and Bantustans, which were the final stage of apartheid before its collapse.

“The borders are being scrambled. The Jewish Nation-State Law and the plan to transfer the Triangle [to a potential future Palestinian state] are part of this blurring. The Green Line is no longer relevant. But scrambling borders helps Palestinians to unite, to organize away from a political boundary that Israel has put in place in favor of apartheid.”

What is the role of Palestinian citizens of Israel here?

“In my doctorate I wrote about the role of Palestinian intellectuals and their liminal situation. They move in many circles but are not full partners in any of them. They participate under the banner of their exceptionalism. They are citizens of Israel, but not entirely. They’re Palestinians but are not supposed to be part of any Palestinian state. They belong nowhere and everywhere.

“I’m observing what’s happening with Palestinians in Israel — the demonstrations in Jaffa and Haifa, the identification with Iyad al-Hallaq, the demonstration in Tel Aviv. These processes are all connected to one another. Palestinians in Israel have to open and dissolve the borders.

“After all, what happened in Israel? Jews became a race, Judaism has become a process of racialization. The task of Palestinians in Israel is to do away with racial boundaries, to begin rolling back colonialism, to broaden the conversation on rights and justice, in place of what’s happening now.”

Will Palestinians in Israel be able to take a leading role?

“The Palestinian struggle began in the diaspora, in the refugee camps, moved to Lebanon and Jordan, and then moved to the West Bank and Gaza during the First Intifada. The center of gravity is now shifting to Palestinians in Israel. Not in the same form, and not using the same tools, but it’s the same struggle — which takes different shapes according to the development of the Zionist project.

“The Jewish Nation-State Law established Israel on the basis of race, and the Palestinians were excluded from the citizenry on the same basis. The battle against them has intensified as they have grown stronger. But despite the current circumstances, Palestinians in Israel are part of the political body — they can participate in elections and enjoy relative freedom. They’re a little like the Coloured community in South Africa, and this allows them to form coalitions with progressive Jewish groups. Their liminality permits it.”

Let’s go back to annexation. Do you think the Palestinian Authority will collapse if it happens?

Maintaining the Palestinian Authority is firmly in Israel’s interest. Israel wants the PA to survive so that it can serve as a subcontractor for Israeli security. After all, who wants to collect the trash in the refugee camps?

“But I also don’t think that the Palestinians want the PA to crumble, they just don’t want it to act as Israel’s subcontractor. The best option would be to re-establish PLO institutions as a political organization, and to turn the PA into more of a municipal body that will see to Palestinians’ needs. This is, by the way, what has happened during the time of the coronavirus.

“I don’t want Israeli soldiers to return to Manara Square [in Ramallah]. I want Israeli soldiers to leave the West Bank.”

Is the PA ready to tackle annexation?

“The situation is very fluid. The economic picture is very bleak. People didn’t get their paychecks this month. So the starting point is very low.

“I don’t know if the [Palestinian] government has a plan. There’s an attempt to provoke a crisis, the first since Oslo. There’s anger at the PA. The sense is that they negotiated for 25 years and deceived people. Every concession they made gave rise to another settlement. I don’t envy the PA — Mahmoud Abbas has sat back and emphasized that he wants peace and has been criticized the whole time. People have told him: you talk peace, they talk settlements.

“Where is this going? It depends on how the international community acts. They sponsored the diplomatic process, and now they need to deal with the consequences.”

And what about if annexation is averted? Will we go back to the status quo?

“A new process has been started that will be difficult to stop. The annexation plan essentially aims to turn a de facto situation into a de jure one. What’s happening in the West Bank today goes beyond repression. Even if the process [of annexation] is stopped, the situation on the ground is intolerable from a humanistic perspective.”

Is it possible to return to the Oslo peace process?

“That would be even more difficult. If you want a two-state solution, you need to involve the international community. I don’t see it happening. I don’t think they’re ready to pressure Israel.

“But the Palestinians are opposed. They’ve been opposed [to Zionism] since 1917 [the year of the Balfour Declaration] until today. They haven’t been defeated. You also need to look at what’s happening around the world, in Europe and in the United States. We’re not isolated. There’s a global fight between a populist discourse and a justice and human rights discourse. The Palestinian discourse is going that way too.”

If stopping annexation meant a return to the status quo, would you prefer it went ahead?

“I really don’t want annexation to happen. I’m not one of those people calling for a bigger crisis. We don’t need to see even more deterioration from where we are today.”

A version of this article was first published in Hebrew in Local Call. Read it here.