As the Bethlehem-bound service taxi left the West Bank village of Abu Dis and the Israeli checkpoint came into sight, the other passengers, all Palestinian men, stopped talking and put their seatbelts on. The driver turned off the radio. Just moments before, music and conversation and laughter had filled the air. Now it was silent, save for the clicking of the prayer beads that swayed from the rearview mirror.

This happened every time a servees approached “The Container” checkpoint: everyone held their breath as though they were diving underwater. But diving comes with the expectation of surfacing. The thing about The Container is the uncertainty — you never know what’s going to happen. Maybe the soldiers won’t even look your way. Maybe they’ll wave you through. Maybe they’ll pull you over and search you. Maybe you’ll end up in administrative detention. Who knows?

It is the uncertainty that terrifies, and it is the uncertainty that made everyone lapse into silence that day in September 2013. Everyone held still. Even the driver seemed to try to minimize his movements. Keeping his hands at ten and two on the steering wheel, he moved as little as possible, just enough to guide the vehicle through the checkpoint.

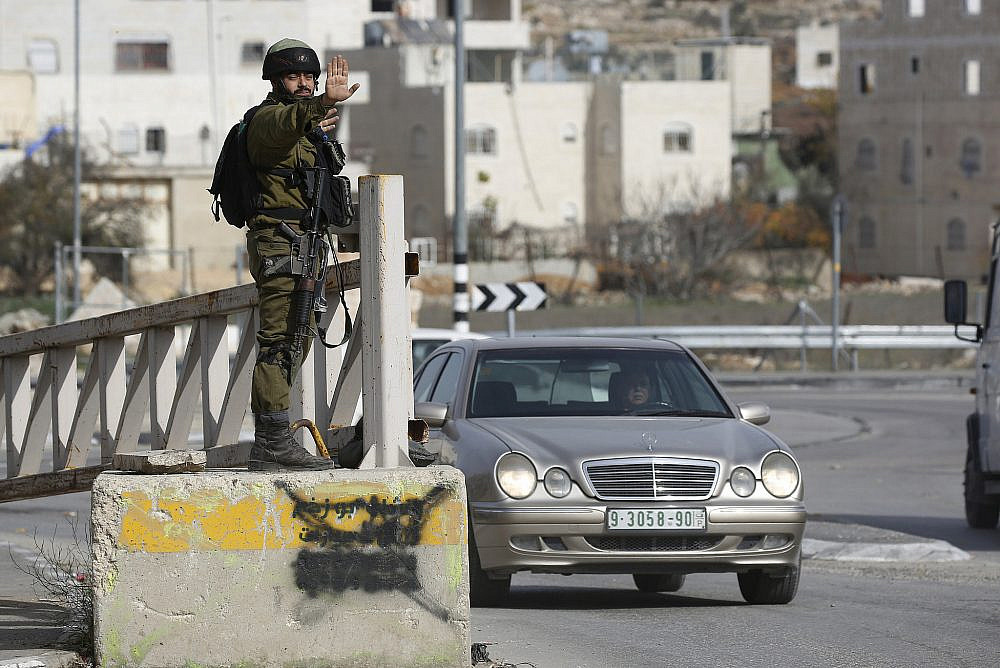

On that day, we bounced over the first set of tire spikes and an Israeli soldier — standing in the road, a gun slung across his chest — gestured for the driver to pull over. It didn’t make a bit of sense because, just five minutes ago, I had cleared this checkpoint going in the opposite direction and they hadn’t been pulling anyone over.

But now they were.

***

That was seven years ago. Although The Container has changed physically, the place and the fear it invokes remains the same. On June 23, Ahmed Erekat was shot dead there by Border Police. A video of the incident shows his car crashing into the checkpoint and hitting one of the officers, after which he runs out and is killed.

Following Erekat’s killing, some media outlets called The Container an “East Jerusalem checkpoint” — a technically true but misleading name that actually covers up the violence of the place. Reading the phrase, even I could mistakenly believe that the checkpoint stands on the Green Line between East and West Jerusalem, dividing the state of Israel from the occupied West Bank. The suggestion that The Container serves some kind of security function also hovers over those words.

But as anyone who has been through that checkpoint knows, The Container in fact divides one Palestinian area from another. While it is in the part of Jerusalem that Israel unilaterally annexed after 1967, it neither protects “West Jerusalem” nor sits on its border. It is jammed into the throat of the Palestinian territories, severing the continuity of the villages on the edge of Jerusalem.

The Container is what’s known as an “internal checkpoint”: a way of keeping a boot on the Palestinians’ neck, and an ever-present reminder that no matter how far you are away from Israel, Israel is constantly watching, always involved in every aspect of your daily life.

“That’s the point of The Container,” my Palestinian husband says, “to remind you they’re always there.” The irony, he adds, is that long before there was a checkpoint in the area, it used to be a road Palestinians took when they wanted to avoid Israeli soldiers or police.

The seemingly ominous name, too, has an unexpected history: before the army took over the spot, there was a shipping container that a local man used as a small dukkan, a shop, to sell drinks and snacks to travelers on that otherwise empty stretch of road hovering above Wadi al-Nar.

***

That day in September 2013, the young soldier — a wisp of a thing, his uniform too big and rolled up to his elbows, the olive green fabric seeming to pool around his body — approached the servees, opened the sliding door, sized everyone up, and asked for IDs. The men, all of them old enough to be his father, obliged the boy, taking their green ID cards out and passing them forward to one passenger, who stacked them and handed the pile over to the boy-soldier. He looked through them, one by one.

When he was finished, he instructed the driver and passengers to close the windows. Then he shut the door, and that was it. No explanation. He just walked away, leaving everyone to bake in the sun for the better part of an hour.

Another soldier eventually opened the door, and without explanation, tossed the IDs onto the floorboards of the vehicle as one would rid themselves of something small, inconsequential, a piece of litter. As though he couldn’t be bothered to hand them back to the passengers to acknowledge their humanity.

With that flick of his wrist, we were free to go.

As the driver pulled out of The Container, clearing another set of tire spikes, the windows opened, the music went on, and the conversation resumed. When we got to Bethlehem, I tried to pay but the driver refused my money. Without me in the vehicle — a white woman carrying an American passport — things could have been much worse, he said.

***

That day, in many ways, was a very typical moment at The Container. And while I carried immense privilege in that servees, the fear of what could transpire consumed us all. The absolute silence as we approached the checkpoint. The total unpredictability. The lack of explanation for anything that was happening. Not knowing when — or for the Palestinian passengers, if — you would make it to the other side of the checkpoint. The fact that all us were on their way not to or from Israel, but to or from one Palestinian area to another.

The checkpoint stands on the only road connecting the north of the West Bank to the south. If you are a Palestinian with a green ID — meaning that you cannot drive through Jerusalem — and you want to get from Bethlehem to Abu Dis or Ramallah, you have to go through The Container. If the army shuts The Container, the West Bank is effectively cut into two.

Just a few months before that September day, soldiers hauled my husband (then-boyfriend) off a servees at The Container and searched him — without cause, without explanation — as he made his way from Ramallah to visit me in Bethlehem. A terrifying experience, it too was typical, aadi, normal. The sort of thing that makes Palestinians think twice about their plans if they involve crossing The Container.

And, definitely, people avoid the place at night.

It was night when, on another occasion, as I made my way back to Bethlehem from Ramallah, I saw a man on the side of the road, hogtied and surrounded by soldiers, his empty car nearby, the doors open. I still remember hearing the other passengers gasping, the sharp intake of breath that rippled through the vehicle, as, one-by-one, they saw the man.

I still remember the sound of fingernails tapping on the glass windows. “Look, look,” the passengers said, keeping their voices low, almost at a whisper, as though they were frightened that someone would hear them pointing it out. As though they were too frightened to hear it themselves.

***

Just two months after that September day, a Palestinian man, Anas al-Atrash, would be killed at The Container, shot to death under mysterious circumstances. The Israeli army would insist that al-Atrash had a knife; his family said that he simply stepped out of his car after he was pulled over.

And then there are the everyday moments: passing through it on the way to school, or work, or an appointment, or to visit a loved one. The constant intrusion on your life of this checkpoint, built by foreign occupiers who aren’t supposed to be here anyways. There you are, sitting in a servees on your way to class, when all of a sudden you’re being pulled over and asked for your ID.

That’s the occupation: a malevolent deity that inserts itself into every last detail of your life, even the most intimate ones.

On that September day, I was on my way to a wedding. The delay caused me to miss part of the celebration. How many Palestinians have been late to or completely missed important moments in their loved ones’ lives due to The Container? How much time has the place stolen?

That was the thing Palestinians told me over and over again when I lived in the West Bank. Our land? We can get that back. But our time cannot be replaced.