As the world began reeling from the outbreak of COVID-19 in March, Israeli authorities were busy with a string of infrastructural projects across the occupied West Bank. They include installing a new section of the separation wall, building bypass bridges for Israeli settlers, digging tunnels, and approving Palestinian-only separation roads in various locations east and southeast of Jerusalem. In pursuing these initiatives, Israel has been working hard to achieve its future geographic and demographic vision for the West Bank, turning what was once described by many as a “temporary occupation” into a permanent reality of apartheid.

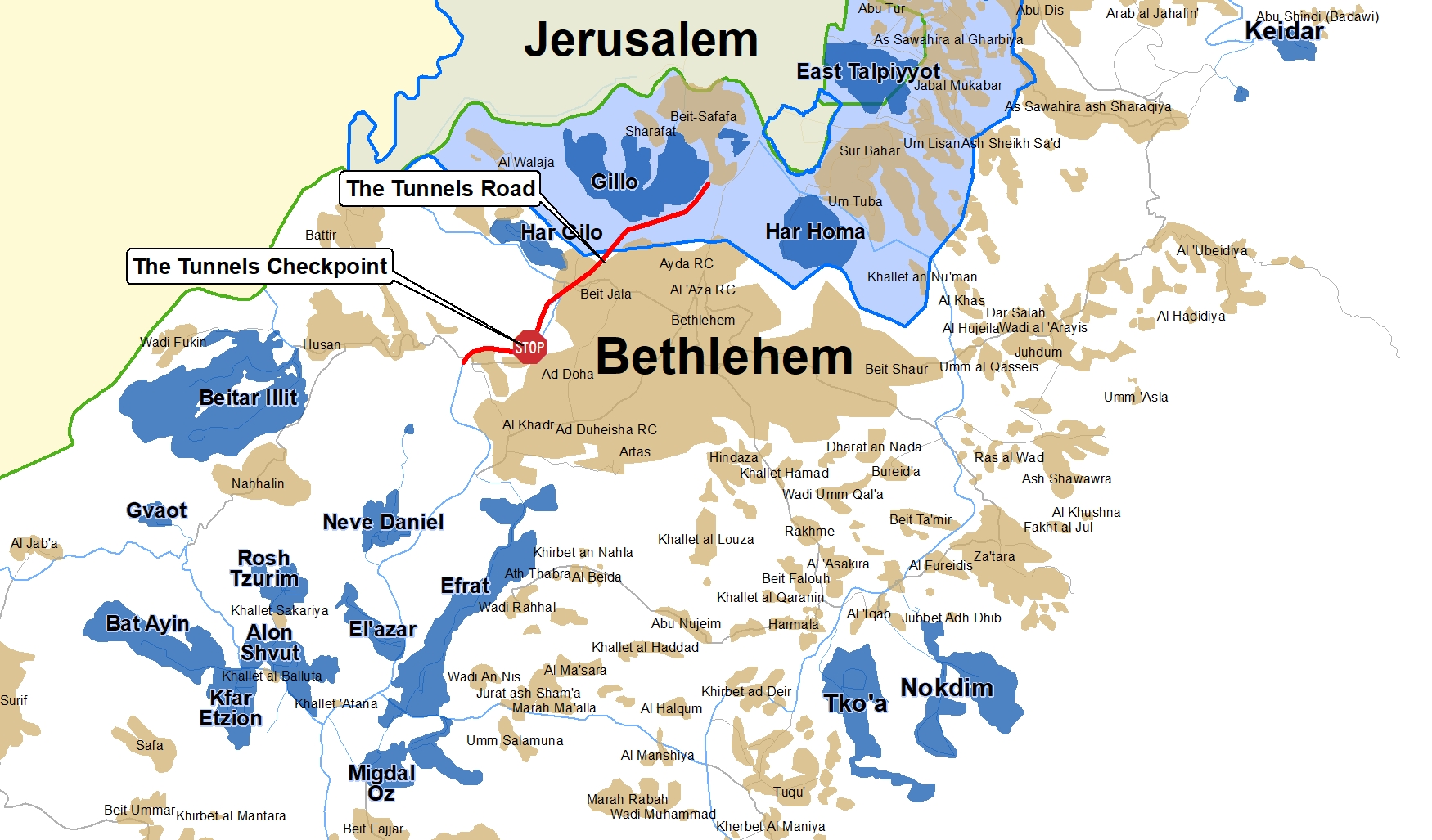

One of these projects has been the expansion of Route 60 — commonly referred to as the “Tunnels Road” — the main highway leading from Jerusalem southwards to the West Bank settlements between Bethlehem and Hebron. Located between Beit Jala and Bethlehem, the road lies between two giant concrete walls and serves vehicles with yellow Israeli license plates only.

The expansion, which began a year ago and is slated for completion in 2025, includes adding two traffic lanes and building two new tunnels next to the existing ones. The goal is to double the entrance capacity of settlers traveling to Jerusalem from the Gush Etzion area, just south of Bethlehem. In order to widen the road, the Civil Administration — the arm of Israel’s military government that governs the 2.8 million Palestinians in the occupied West Bank — confiscated around three acres of land from the Palestinian village of al-Khader and the city of Beit Jala.

The Tunnels Road is one of dozens of so-called “bypass roads” that have been built across the West Bank over the past decades to ensure that settler traffic circumvents Palestinian cities and towns. But avoiding Palestinians isn’t the only goal; crucially, bypass roads allow settlers to commute more efficiently to urban centers such as Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, merging their West Bank localities with daily life in the state. The massive wave of construction of bypass roads since the signing of the Oslo Accords has bolstered the growth of the settler population from just over 100,000 in the mid-90s to approximately 440,000 today.

The expansion of the Tunnels Road — part of the Israeli government’s plan to upgrade and expand transportation infrastructure for settlers in the West Bank — is taking place inside the area annexed to Jerusalem along the eastern edge of the Gilo settlement neighborhood. Additional work is also being carried out in Area C of the West Bank (which is under full Israeli military and administrative control) on the outskirts of Beit Jala.

Now that de jure annexation has been temporarily taken off the table, the settler right is hoping to continue pushing creeping, de facto annexation, and to raise the settler population to one million. As Daniel Seidemann, an Israeli attorney who specializes in the geopolitics of Jerusalem, explains, the infrastructure projects are “geared to erase the Green Line and integrate West Bank settlements [into Israel].”

According to the Moriah Jerusalem Development Corporation, an organization established by the Jerusalem Municipality to develop infrastructure in the city, the one billion shekel project is expected to enhance movement of Israeli citizens between Jerusalem and other southern West Bank settlements, such as Gush Etzion, Efrat, Kiryat Arba, and others.

Moriah’s virtual promotional simulation video shows Israeli vehicles only traveling on the expanded road, while making no mention of any of the invisible adjacent Palestinian towns that lie behind the two walls that surround it. Despite being built in the 1990s on private land that was confiscated from Palestinians, the Tunnels Road is off limits to West Bank Palestinians, apart from Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem, who are allowed to drive Israeli-registered vehicles.

According to the Applied Research Institute (ARIJ), a Palestinian NGO that reports on Israeli settlement activities across the West Bank, the road’s main aim is to bypass Beit Jala and Bethlehem, providing the settlers of Gush Etzion and the Hebron area with a southwest entrance of Jerusalem city clear of Palestinians. In the past, Palestinians could travel between Bethlehem and Jerusalem; today, Bethlehem is surrounded by the separation wall.

Excluding the exiled

The story of the road goes back to July 1948, when Israeli forces conquered approximately 45 Palestinian villages in the Jerusalem area. Thousands of Palestinians were expelled, while others fled to the territory that would become the West Bank.

Approximately 15,000 of these refugees settled in Dheisheh Refugee Camp, built in 1949 just south of Bethlehem, right next to the road that connected Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Hebron. When Israel expanded its colonial project to include the West Bank in 1967, Israeli authorities began drawing up plans to allow Israeli settlers to safely use the road to reach their settlements in Hebron and southern Bethlehem. Over the years, Israelis who used Route 60 were frequently targeted by stones and Molotov cocktails thrown by the Palestinian refugees that Israel had denied their right of return.

“The Israeli army limited our access to the main road by blocking all but one exit,” said Haitham Abu Ajameya, 49, a resident of Dheisheh, whose family was kicked out of Mighallis, a village west of Jerusalem, during the Nakba.

Abu Ajameya remembers how the Israeli army installed a fence to surround the camp, while preventing the refugees who lived in Dheisheh from using the road between 1986 and 1995. “Only UNRWA staff were allowed to drive in and out. Refugees used to cross on foot after getting inspected by soldiers at the turnstiles,” he recalled.

Residents of the camp still remember when the Israeli military government had planned to demolish some of Dheisheh’s housing units, in order to leave a 30-meter buffer zone between the camp and the road to secure Israeli citizens. That idea never took off, but the Israeli authorities had another plan up their sleeve.

In the late 1980s, the Israeli military informed Palestinians living at the western edge of Beit Jala that their homes would be demolished, even though they were previously built with permission from the military authorities. The reason was that Israel had decided to re-route the Jerusalem-Bethlehem-Hebron road, so that Israeli citizens could drive without passing near the Dheisheh camp.

“They told us there will be a new road that will pass through our land,” said Nasim Duqmaq, one of the residents who had been living in the homes slated for demolition. Although Duqmaq’s lawyer managed to prevent the demolition of his house, the project itself was not canceled.

Today, the road’s southern tunnel runs right under Duqmaq’s home, which allows Israeli vehicles to avoid entering Bethlehem on their trip to Jerusalem. After exiting the tunnel, a walled bridge flies over Palestinian residents of Beit Jala and Bir Onah, who are not allowed to use it, while connecting Israeli drivers with the road’s northern tunnel that leads into Jerusalem.

During the Second Intifada, the Israeli army built a checkpoint at the entrance of the road, preventing Palestinians from using the road to travel to Jerusalem. The checkpoint remains, despite the fact that armed resistance in the area has long since abated. Even Palestinians who hold travel permits can only get to Jerusalem on foot through certain checkpoints designated for Palestinians only.

Since then, the method of re-routing roads for the sake of Israeli settlers has increased. Today, there are dozens of these roads that facilitate Israeli settlers’ movement across the West Bank and help them to avoid traveling through Palestinian areas.

Settlements’ lifeline

The Tunnels Road is a prime example of just one of the methods Israel has been using to entrench an apartheid, one-state reality. The Trump “peace plan,” which allowed for the Israeli annexation of large swaths of the West Bank, may have failed to take off, but the Israeli government has had countless means to gradually annex land for decades.

As human rights groups have shown, including in a new report this month by Breaking the Silence and the Israeli Centre for Public Affairs, road construction, and particularly bypass roads, have served a central function in Israel’s colonization of Palestinian land.

In the 1970s, Israel realized that building roads for settlers inside the West Bank would be key to connecting them to Israel’s metropolitan areas. When the Oslo Accords designated Palestinian urban areas, such as Bethlehem and Dheisheh Refugee Camp, as Area A under the control of the Palestinian Authority, the Israeli government decided to invest more vigorously in its bypass roads to ensure settlers would remain in Area C while driving through the West Bank.

The bypass roads also allowed for rapid suburbanization of West Bank settlements, particularly around Jerusalem, based on what Breaking the Silence calls “fully segregated infrastructure.” According to media reports published in December, Israel is currently working on several new bypass roads, including one that would bypass Al-Aroub Refugee Camp, midway between Bethlehem and Hebron, as well as a road that would circumvent the Palestinian city of Huwwara, near Nablus.

Despite Israel’s investment in West Bank infrastructure over the years, settler leaders felt that the government was not spending enough money to actually increase the settler population in the territory. The growing power of the settlers over the past five years, which dovetailed with the Trump administration’s enabling of Israel’s expansionist pursuits, led them to demand — through protests and even hunger strikes outside the Prime Minister’s residence in 2017 — more money for infrastructure. The protests worked, and the settler leadership was granted a total of NIS 200 million for a single year.

That investment reached a high point this year, as Transportation Minister Miri Regev announced a massive infrastructural investment project to be completed by 2045, which will provide all Israeli citizens with a comprehensive network of roads across Palestine-Israel intended for Israeli citizens alone, which will allow drivers the ability to travel without having to pass through or even see a Palestinian enclave.

Regev called the plan “an exciting day for the settlements and for the State of Israel, which builds and is building in all areas of the homeland.” The minister said the plan offers a “holistic vision” for “a future development plan for the region.”

While it is not entirely clear just how much of the project will be implemented, massive construction projects meant to facilitate settler movement are already taking place in the Jerusalem area. This includes a project in the adjacent settlement of Ma’ale Adumim, where Israel plans to build 19,000 new housing units, closing off the area to Palestinian traffic, and making it possible for settlers to get to Jerusalem without encountering a single checkpoint.