The COVID-19 pandemic is compounding the already precarious situation that refugees around the world are in. Palestinian refugees in Jordan’s Jerash camp are especially vulnerable, given the existing public health challenges and severe poverty.

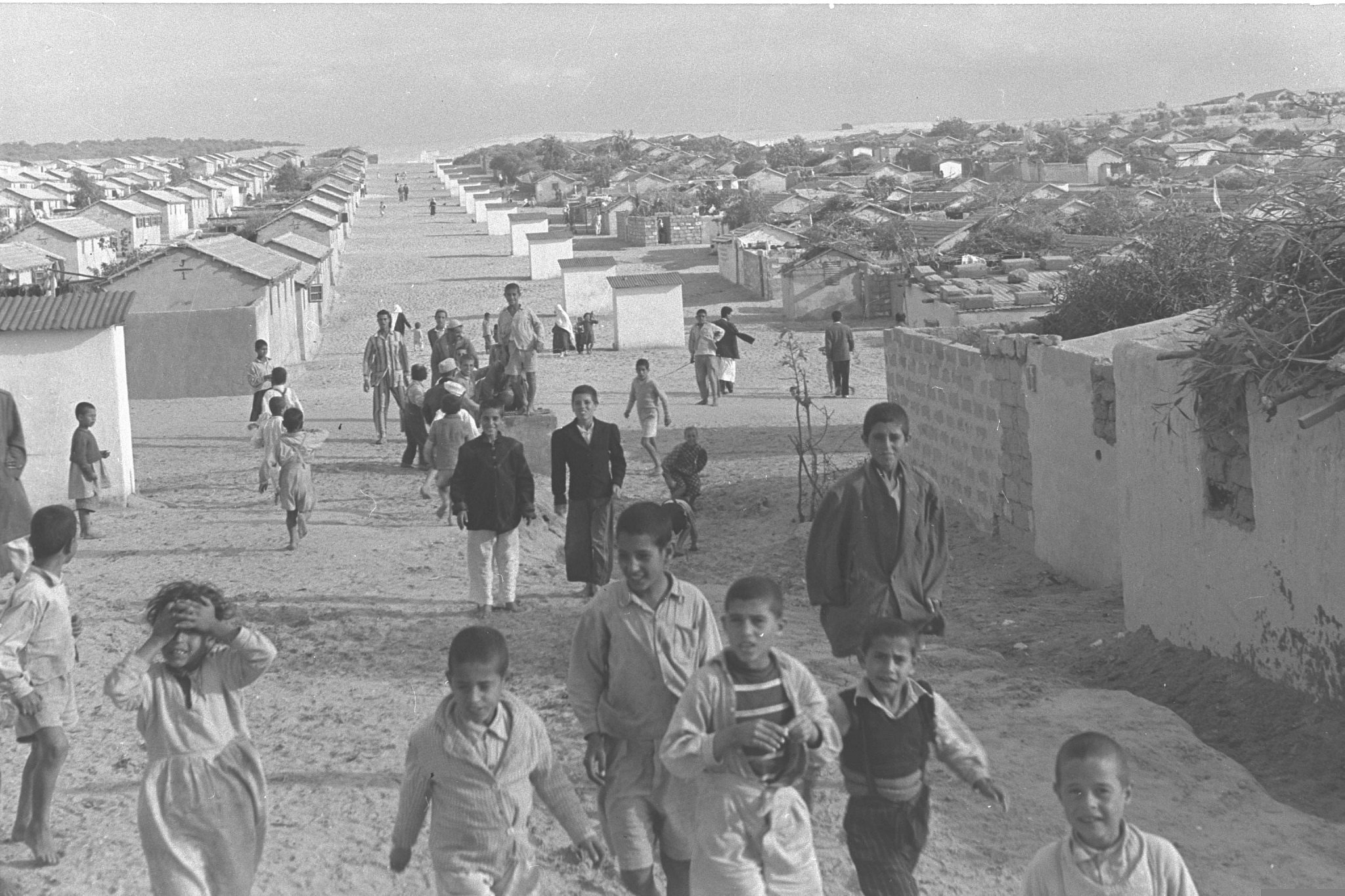

There are more than two million registered Palestinian refugees living in Jordan. Jerash camp is home to an estimated 30,000 Palestinians whose elders fled Gaza in 1967, after Israel occupied the territory. Unlike most Palestinian refugees in the Hashemite Kingdom, they never received Jordanian citizenship, which impacts their access to work prospects, educational opportunities, and healthcare, among other rights enjoyed by Palestinian-Jordanians.

Before the Jordanian government instituted a lockdown to contain the spread of the new coronavirus, the camp, known locally as Gaza Camp, was deemed by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), the U.N. body that delivers vital aid to some 5.3 million Palestinian refugees across the Arab world, as the poorest of the 10 official Palestinian refugee camps in the country.

Based on a 2013 report by the Fafo Institute for Applied International Studies — the latest UNRWA study released on the socio-economic conditions of Palestinian refugees in Jordan — refugees who were displaced (either for the first or second time in 1967) from Gaza and their descendants are more than three times as likely to be among the most impoverished, living on less than $1.25 a day. Over half of the camp’s refugees have an income below the national poverty line of JD 814 ($1,148). Unemployment rates in the camp are close to 40 percent compared to 14 percent for Palestinian refugees in Jordan, according to a 2018 study by the Palestinian Return Centre.

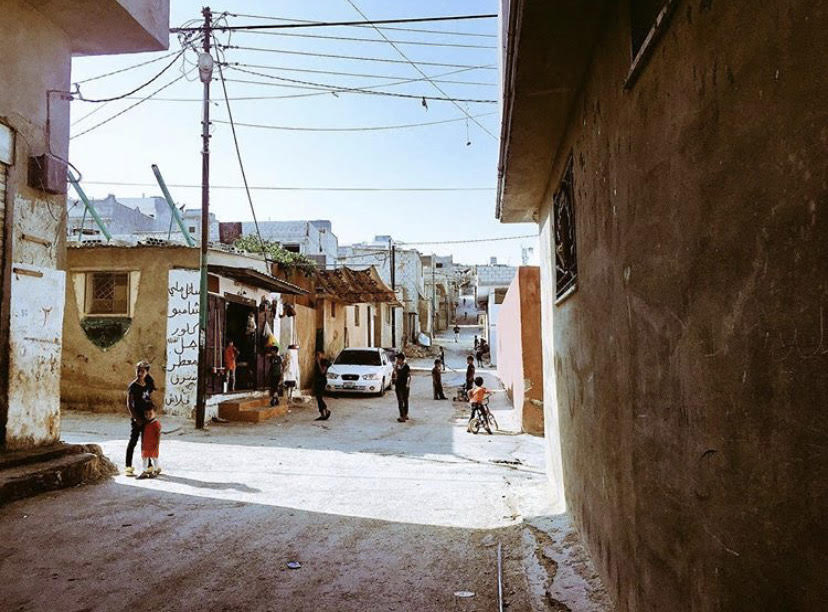

The camp’s residents were also already facing a myriad of public health issues prior to the pandemic. More than 65 percent of the buildings contain asbestos and corrugated zinc, and have not been overhauled since their construction. There is limited access to clean water and a “reeking sewage system,” states the Palestinian Return Centre report. Garbage is strewn in the streets, as UNRWA had to reduce its trash collection after the United States slashed its funding to the relief agency in 2018.

Jerash camp has the highest number of Palestinian refugees in Jordan without any health insurance — a staggering 88 percent of the camp’s population. However, children under 6 years are eligible for public health insurance and are treated at government health facilities for free, like all Jordanians.

According to the Palestinian Return Centre report, Jerash camp refugees have access to free healthcare through local UNRWA-run clinics, “which offer very basic services.” If they venture outside to a government hospital, they must pay guest fees for medical services, as if they are foreign nationals seeking treatment abroad. UNRWA may partially subsidize these treatments depending on a refugee’s economic status, but many find the cost of treatment unaffordable still.

In 2019, I visited the camp as part of an academic research study. I spoke to around 15 camp residents who recounted how ambulances cannot reach many parts of the camp, or how they have to rely on using the national ID cards of sympathetic Jordanian citizens to access critical treatment in extreme cases.

Muhand Salem, 23, was born and raised in Jerash camp. He studied engineering but has been unemployed since graduating. I last saw Muhand in 2017, when I began volunteering with a nonprofit organization that operates there. We stayed in touch on social media, and following the coronavirus outbreak, I asked him how he is faring via Instagram messages.

Given Jordan’s economic crisis, life at the camp was already hard, he said. After years of exempting Gazans from having to apply for work permits, in January 2016, the Labor Ministry announced it as a requirement. Each work permit cost around $250 per person — a fee many Gazan refugees cannot afford on a yearly basis.

“Companies started to lay off many of their ex-Gazan workers or stopped employing them,” added Muhand. “By the end of the year, most employees faced problems — from being unable to obtain work permits, to pressures in being laid-off or being unable to find new jobs.”

Most breadwinners at the camp earn a daily wage, explained Muhand. During the summer, these kinds of work opportunities tend to increase, and people would save their earnings to help them get through the slower winter months.

But then COVID-19 hit. Since the coronavirus broke out in the early spring, most refugees had already spent their winter savings, he said. Now, “most families living in the camp are struggling to provide the very basics necessities for themselves and their families.”

“We are constantly losing the youth’s energy, even prior to COVID-19, because of the economic situation,” continued Muhand. “There is no goal for us to strive for.”

Directing people who are already struggling financially to shelter at home means “telling them not to work on that day, not to earn [a living], and to live that day without eating.”

Many organizations are working to ensure that Palestinian refugees, especially those in Jerash, are taken care of during this crisis. Grassroots organizations like One Love Sama Gaza are providing Palestinian refugees in Jordan with food packages during and after the COVID-19 crisis. American Near East Refugee Aid (ANERA) recently announced a partnership with Medical Aid for Palestinians’ branch in Jordan to deliver vital medicines, including vitamin D supplements for women.

While the work of these organizations is important and vital, it is focused on short-term relief. The COVID-19 crisis is highlighting the need for long-term, structural solutions when it comes to the rights and needs of Palestinian refugees — ones that not only respond to their humanitarian and economic difficulties, but that also address the root of their problems: their initial displacement.