“Looting of Arab Property in the War of Independence,” Adam Raz, Carmel Publishing House, 2020 (Hebrew).

I brought a few nice things from Safed. I found for Sarah and myself some beautiful embroidered Arab dresses that our local tailor might be able to fix up. Spoons, neckerchiefs, bracelets, a Damascene table and a coffee set of beautiful silver cups, and then yesterday Sarah also brought a gorgeous, completely new Persian carpet, I’ve never seen something so beautiful. A living room like that can hold its own even among the richest folks in Tel Aviv.

These gushing lines from a letter don’t describe shopping items, but bounty: an Israeli soldier’s private profits from the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from the city of Safed during the war of 1948.

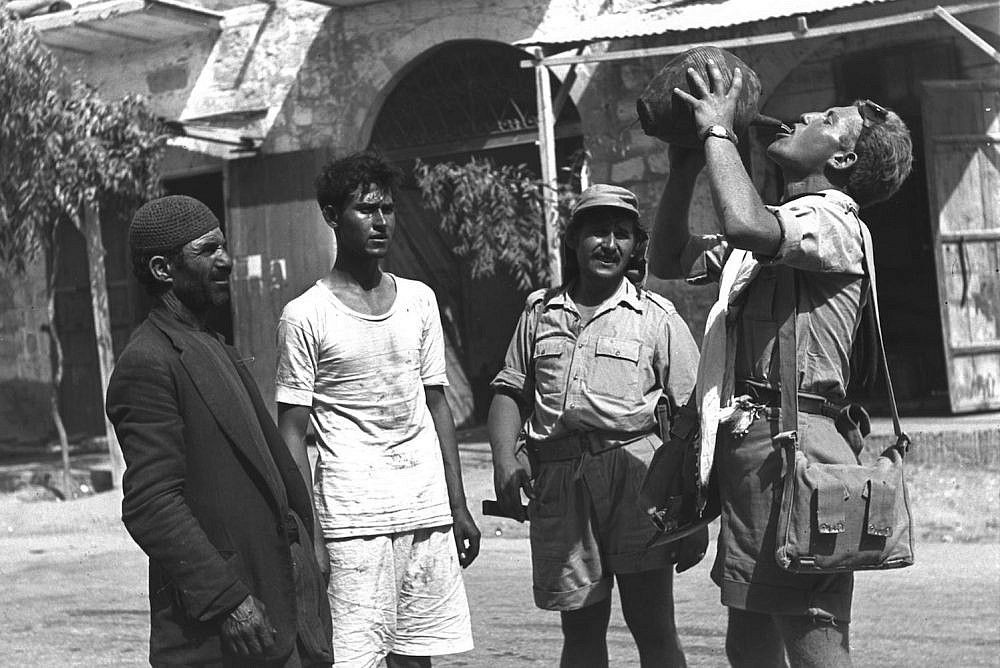

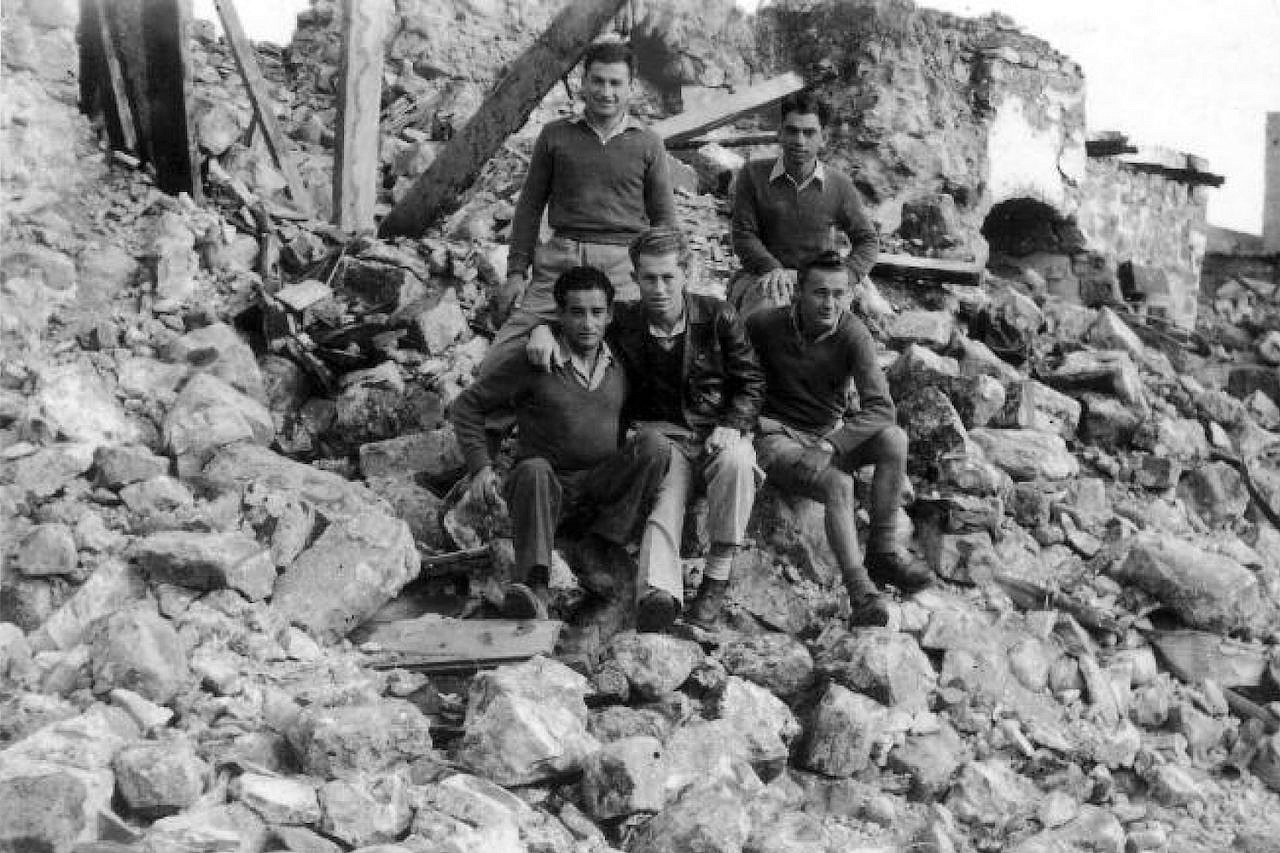

Alongside the massacres, expulsions, and expropriations of that war, Israelis — combatants and civilians alike — stole and looted an astonishing range of Palestinian belongings: personal items, musical instruments, livestock, agricultural produce, agricultural machinery, antiquities, and the contents of entire stores and libraries. The full scale and value of private plunder has never been established conclusively, as only items expropriated by or handed over to the state were documented in detail.

This mass theft is the subject of “Looting of Arab Property in the War of Independence,” a new book by historian Adam Raz, who works as a researcher at the Israeli archival group Akevot. The book concentrates specifically on the looting of movable assets belonging to Palestinians who were expelled from their land in 1948 and never permitted to return.

Raz separates this particular practice from the expropriation of Palestinian land by the nascent Israeli state, in a bid to trace acts initiated not from the top “by political decree,” but rather “from the bottom up” — by neighbors who cohabited in a shared space until the very eve of war. This experience, Raz believes, proved formative in shaping the position of the wider Jewish community against the return of Palestinian refugees.

Part One of the book is dedicated to a dense and rich documentation of the looting, utilizing documents from Israeli archives, clippings from contemporary Hebrew newspapers, diaries and memoirs by Zionist statesmen, and commemorative brigade books and memoirs by Israeli veterans of 1948. In Part Two, Raz offers his analysis of the political ramifications of the looting, arguing that individual acts of looting had considerable influence on the establishment of Israel’s policy of wholly rejecting the repatriation of Palestinian refugees to their homeland.

Through their acts of looting, Raz argues, the looters became “passive partners in the policy that sought to empty the land of its Arab residents,” even as various patterns of national denial and suppression endowed the looters with a kind of social amnesty for their crimes. The looting turned the prospect of Palestinian return into a concrete threat against the economic interests of the looters, who would ostensibly have to return the stolen goods to their rightful owners. The lack of a proactive policy to secure Palestinian property, Raz adds, amounted to a key mechanism for acquiring Israeli society’s support for creating a Jewish-only, Arab-free space — a policy which Raz says became “hegemonic over the course of the war.”

Raz’s book makes an important contribution through the sheer scope of its documentation of looting during the 1948 war, which had previously attracted little academic debate. It also roused various gatekeepers of Zionist historiography to explicitly defend the Israeli policies of 1948. However, the book relies almost exclusively on materials from Israeli archives and the work of Jewish Israeli researchers on the 1948 war (with two exceptions, Sabri Jiryis and Mustafa Abbasi). In doing so, it preserves the practice of ignoring and erasing the extensive Palestinian body of work on the Nakba and its consequences.

Raz focuses on proving the Jewish community’s complicity in the looting, examining the ramifications that this complicity had for coalescing Israeli society around a conspiracy of silence, and the manner in which this conspiracy formed the basis for justifying the prevention of the refugees’ return. To his credit, Raz does cite claims made by Palestinian owners, preserved in Israeli archives, and takes care to cite their names in Arabic to compensate for the corruption and misspelling of these names in Israeli documents. However, the fact that even the citations are drawn from within the boundaries of Israeli government records indicates the positioning of the book within the limits of the Israeli discourse.

This positioning informs the very basis of Raz’s analysis of the looting, as well as his approach to the Nakba as an exceptional event — not so much as part of the continuum of Zionist policy, but rather the product of cataclysms that took place in the few short months of the war, and in the context of the unique political opportunities the war created.

Raz stresses the debates within the Zionist movement concerning the looting, focusing in particular on the role of David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, in abstaining from any action to protect Palestinian property. But Raz ignores the fact that all sides of these Zionist debates shared the fundamental view of Palestinians only as a future minority in the Jewish nation-state to be. By doing so, he also ignores the way in which Zionist colonial policies and the ostensibly liberal civic order established in Israel were inextricably linked, forming the infrastructure for what historian Shira Robinson dubbed “the liberal settler state.”

‘A hierarchy of knowledge’

For Palestinian refugees, the participation of individual Jews in the looting of their property doesn’t require archival evidence; those belongings are part and parcel of Palestinian memories before their expulsion, and the theft is inseparable from Israel’s expropriation of their land.

Ghassan Kanafani’s novella “The Return to Haifa” describes the return of two Palestinian refugees — Said and Safiyya — to their homes in Haifa, which they were forced to flee, after the opening of the Mandelbaum Gate in the former Jordanian-Israeli border across Jerusalem in the wake of the 1967 war. The novel describes the various items the couple left behind and the memories they evoke:

The entrance seemed smaller than he had imagined it and felt a little damp. He saw many things he had once considered — and for that matter still considered — to be intimate and personal, things he believed were sacred and private property which no one had the right to become familiar with, to touch, or even to look at. A photograph of Jerusalem he remembered very clearly still hung where it had when he lived there. On the opposite wall a small Syrian carpet also remained where it had always hung. (Returning to Haifa and Other Stories by Ghassan Kanafani, translated by Barbara Harlow and Karen E. Riley).

The objects — the photograph, the Syrian carpet — are what gives the home its meaning. They are stores for the layers of both Palestinian memory and of the present, in which sacred and intimate things were violently snatched from their owners and given away to strangers. Kanafani’s novella was published in 1969 and has since become a canonical text of the Palestinian national struggle, faithfully reflecting the way in which the looted property was perceived as an essential component of the overall picture of expulsion.

Historian Adel Manna noted that looting, especially by Israeli military forces, “was routine. It figures in a great many descriptions [of the events] by refugees and residents of Galilee villages.” In his book on Nakba survivors in the Galilee and in Haifa, Manna relied on interviews he conducted with village residents, on local historians, and on autobiographies and memoirs by Palestinians where descriptions of looting took center stage.

Fellow Palestinian historian Sherene Seikaly, meanwhile, used a list of 52 damaged or stolen items made by her grandfather (a Palestinian “man of capital” from Akka rendered a dispossessed refugee) as a basis for understanding the behaviors of refugees who remained under Israeli rule. Seikaly highlights the ways in which a simple inventory can instruct us on the collapse of entire worldviews, lived experiences, personal and social networks, and cultural practices that existed in the social circles to which her grandfather had belonged.

This entire spectrum of sources is absent from Raz’s book. In the introduction, Raz states that his aim is to “shed light on an insufficiently familiar aspect of the history of those years: the involvement of significant swathes of the Israeli society, both combatants and civilians, in the looting of Arab property.” This presentation of the looting as an “insufficiently familiar aspect” of the war belies the author’s disregard for the Palestinian perspective and the presence of the looted property’s stories in Palestinian testimonies.

This position thus establishes a hierarchy of knowledge, which prioritizes institutional archival material over the patterns of collective knowledge that coalesce outside the archival reach. The same position explains Raz’s distinction between looting, which he dubs as “illegal activities,” and the “legal” expropriations of land and other property during combat and after the war.

The Tantura massacre is a principal example of this dynamic. Scholar Samera Esmeir analyzed the way in which, during the trial of Teddy Katz — an Israeli doctoral student who was sued by former Israeli soldiers for his research on the massacre — Israeli authorities only considered oral testimonies viable if they recorded all the specific details of a particular massacre as coherently as official documents.

The testimonies, however, consistently describe massacres not as isolated incidents but as part of an overall reality of expulsion and dispossession. As such, Esmeir argued against attempts to use oral testimonies to learn about ostensibly exceptional events as if they were detached from the overall context of war and dispossession; these atrocities were not transgressions from the norm, but part of the norm itself.

In other words, Raz’s attempts to isolate the looting as a distinct and unusual event, and to recast the looter as a norm-breaker and a criminal, can only seem valid if we adopt the perspective of the perpetrators — which is the point of view preserved by official archival documents. For the victims of the Nakba, meanwhile, the distinction between the “rule” — the enforced dispossession, expulsion, and expropriation — and the “exception” of individual acts of plunder, simply does not exist.

The moral colonizers

The reliance on archival documentation leads Raz to focus on how key figures in the Zionist movement reacted to the looting phenomenon in real time. This further allows Raz to identify what he believes is the heterogeneity of the Zionist movement.

For example, according to Raz, David Ben-Gurion’s hands-off approach to the plundering of Palestinians and his view of the war as an instrument for shaping the new society was a minority position even within his own party, and “hugely controversial among the leadership of the wider Zionist movement.” Nevertheless, “by way of manipulation,” this position soon achieved dominance, Raz concedes.

But if we look closer at what Raz cites as examples of opposition to Ben-Gurion, we find that, alongside the rejection of looting as a crime that damages the moral image of the Zionist subject, no politician of note challenged the aspiration to create a polity centered on Jewish-Israeli hegemony. This inherently required transforming the Palestinian majority into a minority — inevitably, through violent means — but also achieving international legitimacy for Zionist colonization, a policy-shaping consideration that Raz doesn’t even acknowledge in the book.

One example Raz picks is Yisrael Galili, then Chief of Staff of the Haganah, the Zionist paramilitary group that would chiefly form the Israel Defense Force. Raz claims that, unlike Ben-Gurion, Galili actively tried to prevent looting, and that “his position toward the Arab community in the country and toward the future of the State of Israel’s relationship with the region was quintessentially different to Ben-Gurion’s.”

Raz’s claim is based on Galili’s orders regarding “behavior with surrendering [Palestinian] villages,” which stipulated that “in any case of request for Jewish protection you should consider carefully whether to leave the Arabs in their place or to relocate them to the rear.” In other words, submission and appeal for Israeli control are the preconditions for treating Arabs as equals.

Another ostensible opponent of Ben-Gurion was Minority Affairs Minister Bechor-Shalom Sheetrit, who is presented as someone who “vocally fought against the dominant policy.” But his position primarily illustrates how demands to stop the plunder were still rooted in a worldview that saw Palestinians only as a future minority in a Jewish state, and primarily sought to prevent the Zionist movement from being tainted with the crime.

Sheetrit, who perceived his ministry as being tasked with forging a relationship between “the Jewish regime and the Arab minority,” saw the question of Palestinian property as a litmus test for the Zionist government:

Over a hundred communities have been evacuated by their Arab dwellers… some of them took their belongings with them… but some abandoned their belongings behind and have put us before a test. We must withstand this test and prove to them and to the world at large that we are a civilized people, ready and willing to take up the responsibility of safeguarding their possessions, and to maintain fair and normative relations with those who desire to stay among us or to return to us.

Like Galili, Sheetrit derives the Zionist movement’s duty toward the Palestinian refugees’ property from their submission and willingness to exist as a minority ruled under Jewish hegemony. Their property is described by Sheetrit as “abandoned” — a choice of words that is meant to justify its expropriation from its rightful owners, and to legitimize the state’s positioning as its rightful guardian. Sheetrit also places the onus on the refugees to decide whether they want to “stay among us.” In other words, to receive the fair treatment that Raz eulogizes, the Palestinians must first agree to accept their new inferior status.

Constitutional lawyer and scholar Hassan Jabareen has indicated that one cannot analyze the status of Palestinian citizens of Israel without considering the Nakba and the fact that their civic identity was formed under colonial subjugation and the existential dread of total elimination, which led to a reluctant alliance with the Jewish sovereign. Under colonial citizenship, he argues, legal rights are conditioned on the willingness of a subjugated community to accept its defeat. Citizenship thus becomes an anchor for Jewish supremacy, and any support Palestinians might voice for their own national interest is recast as rooting for the enemy.

Shira Robinson, in turn, notes that ensuring civil rights for Palestinian citizens was essential for legitimizing the settler state in the international arena and for pushing on with the colonizing agenda, up to and including multiple legal systems in the same sovereign state, such as the military rule over Palestinian communities inside Israel from 1948 till 1966. She notes the evolution of an internal coexistence discourse that saw Palestinian citizens of Israel separated from the rest of the Palestinian people and labelled as “Israeli Arabs” or “Our Arabs,” subject to exclusive Jewish rule.

Robinson’s and Jabareen’s arguments allow us to consider the political meaning of the Israeli opposition to the looting elevated by Raz, with fresh emphasis on how problematic it is to discuss plunder as “illegal” activity distinct and separate from the wider dispossession of Palestinians. To these Israeli critics, securing Palestinian property amounted to realizing the Jewish state’s liberal aspirations, conditioned on the Palestinians’ powerlessness and surrender. The concern isn’t so much with the Palestinians’ property as with the moral image of the Jewish subject and the “good name of the Zionist movement.” It is especially telling that looting was often decried as a crime against the state rather than against Palestinian civilians, as, according to a newspaper report cited by Raz, these “abandoned” belongings were widely seen as “government property.”

This is particularly jarring when Raz attempts to position Yigal Allon — one of the-architects of the expulsions and ethnic cleansing of 1948, and later of the military occupation of 1967 — as a prominent opponent of the looting who lamented “the dangers that assail man’s character among us is greater than they’ve ever been.” Decrying looting and the cracks it sends through the liberal order, and driving the dispossession of Palestinians from their land, appear to be two sides of the same coin: the emergence of the liberal settler state.

An absence of colonial context

Raz’s analysis of looting as a distinct, separate, phenomenon echoes a wider problem: the view of the Nakba as an isolated event outside the wider pattern of Zionist settler-colonialism. Raz attributes the heterogeneity he sees within the Zionist movement to debates among its leadership on how to best implement the partition plan freshly adopted by the UN General Assembly. The majority, he claims, vied for a gradual transition from the British Mandate to the establishment of two nation-states as envisioned by the plan. A minority, however, sought to “escalate the conflict to bring forward a decisive battle” over the land.

This approach, accompanied by an assumption of “an increasingly extremist Arab position,” preserves the widely shared trope that sees the 1947 partition plan and the Zionist leadership’s willingness to endorse it as signs of moderation. This occurs even as Raz stresses that Ben-Gurion “had no intention of adopting the partition plan to the letter,” and sought to secure far wider territorial boundaries than the plan suggested.

Furthermore, Raz ignores the fact that the 1947 plan was actually a certificate of international legitimacy to the accomplishments of Zionist colonization and its claim to sovereignty. The Zionist accent to the plan has long been presented as a compromise; it was, in fact, an unqualified triumph, rooted in the international community’s blatant disregard for the national aspirations of the majority Arab population in mandate-era Palestine.

As Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi shows, the partition plan included on the Israeli side of the border some of Palestine’s most fertile lands (about half of which were privately owned by Palestinians), and severed the cities that remained on the Palestinian side of the partition from much of their own fertile lands. The main water resources and the only airport in the country with international connections were also assigned to the Jewish state. The Arab state envisioned by the plan was thus already destined to be economically-reliant and resource-dependent on the Jewish state, rendering moot any discussion of an equitable union between the two states.

Understanding the way in which the partition plan served the economic and political interests of the Zionist movement highlights how problematic it is for Raz to present the Nakba as exclusively the product of one political line among many, championed by Ben-Gurion. The Nakba cannot be properly understood outside the long-term historical pattern of settler-colonialism, of which the partition plan was just one product. The aspiration to create segregationist Jewish spaces cleansed of meaningful Arab presence was one of the clearest characteristics of the colonization policy pursued by the Zionist movement, especially with the establishment of its Palestine Office led by Arthur Rupin.

In this light, Raz’s claim that the prospect of unbridled looting helped to mobilize the Jewish community behind ethnic cleansing weakens. A much likelier motivator was a political tradition of no less than 40 years, which had already relied heavily on direct Jewish settlement, the removal of Palestinian peasants through the purchasing of their land from absentee landlords during the Ottoman period, and later the utilization of British colonial power and violence to procure the Zionist movement’s success (as argued by Areej Sabbagh-Khoury in her dissertation study of the Ha-Shomer Ha-Tzair kibbutzim on the outskirts of Marj Ibn Amar/Jezreel Valley).

This absence of the colonial context from Raz’s analysis is reflected in the absence of any consideration of a future of decolonization and the return of Palestinian refugees. If anything, looting is made to appear as another factor that precludes the possibility of return.

Among other examples, Raz highlights the change of tack that took place in the Minority Affairs Ministry, which went from supporting the return of the refugees to seeking “to prevent Arabs from returning to the land by informing them that all their property had been lost.” In other words, the fact that mobile Palestinian property had been vandalized or stolen created a political reality that necessitated denying the right of return; it is the looting that firmly established the war as a point of no return.

Raz’s argument — which relies heavily on presenting the Minority Affairs Ministry as initially opposed to Ben-Gurion’s cleansing policy but eventually compelled to align with him in light of the irreversible reality created by the looting — has considerable political implications for the present day because it rejects the possibility of return, and therefore of decolonization.

The Palestinian perspective, however, belies Raz’s blindspots. In the northern town of Eilabun, for example (which Raz cites in passing but Manaa explores in greater detail), Palestinian residents who were displaced by Zionist forces refused to accept the verdict of refugeehood, and used various methods to successfully return to their land in November 1948, despite the loss of stolen property. Such cases show us that return might be exhausting, painful, and traumatic, but nevertheless possible. They also tell us much about the refusal to see looting as a point of no return; about the the right of return as a vital link in the process of decolonization; and about the opening up of the historical debate to a future yet to come.