Warning: Graphic images and details of violence and bodily harm.

“I lost my life while I’m still alive. Locked in my bed, I am unable to look around my village or into the future.”

Harun Abu Aram, 25, lives in an improvised hospital bed in the middle of a desert. He has lived here, in his paralyzed body, for 572 days, ever since an Israeli soldier fired a bullet into his spinal cord. The Abu Aram family, who built the tent in which Harun now lives, spend all of their waking hours working to keep him alive.

The ethnic cleansing of Masafer Yatta, located in the South Hebron Hills in the occupied West Bank, has accelerated in recent months. After a May 4 Supreme Court ruling — which allowed the state to start forcibly expelling Palestinians from eight villages in the area to make way for a military firing zone — bulldozers arrived to raze dozens of homes.

The military also conducted a month-long weapons training, and the state increased the tracking of residents and targeting of activists in the region. The eight villages located within ‘Firing Zone 918’ are home to over 1,000 Palestinians, all of whom are living through an ongoing violent nightmare.

However, the erosion of safety and stability, and the kind of state violence that paralyzed Abu Aram, has been a constant in Masafer Yatta long before the ruling. For generations, Palestinians have fought to survive against the violent acts of the military and settlers. Explicit state policies — some of which were instituted during the popular uprisings of the First Intifada — helped to systemize this violence.

In 1987, then-Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin ordered the Israeli army to “break the arms and legs” of those who dared to resist the occupation. This order was intended to weaken the uprising and to undermine the bodies and resiliency of Palestinian resistance. Thirty-five years later, Rabin’s orders have been normalized as a tactic of silencing Palestinian activists and forcibly displacing the entirety of Masafer Yatta.

These are precisely the mechanisms of violence that have devastated countless lives over the course of Israel’s occupation. In contrast to death, the scarred body is both a living memory of the past and a daily reminder of the present struggles to survive. Here we share the stories of a number of residents of Masafer Yatta who have been left with physical scars following attacks by settlers and soldiers, in order to tell their stories of survival, grief, and the process of relearning their own bodies in the face of unending violence.

Khaled Al-Najjar

Twenty-one years ago, while I was grazing my sheep with my son, I watched an Israeli settler borrow a soldier’s assault rifle in order to shoot me in the stomach. As he got on his knees and pointed the gun in my direction, I told my son to run, fearing the bullet would hit him. It didn’t, thankfully. But it instead struck me in the abdomen, and my life has not been the same since.

My name is Khaled Al-Najjar and I am 69 years old. I have spent my life in the village of Qawawis in Masafer Yatta, where I work with my family to cultivate land and tend our livestock.

Our life in Masafer Yatta was routine and quiet, until Israeli settlements began to spread throughout the region. Each new settlement has been followed by waves of extremist violence, as the settlers try to prevent us from grazing and cultivating our lands that surround their settlements. In 1998, the outpost of Mitzpe Yair started being built a few hundred meters from Qawawis. Even in those early days, when there were only a few caravans settled, the Israeli army and the outpost’s private security guard were working together to prevent us from grazing on our land.

By 2001, shepherding on our land had become routinely dangerous. On Jan. 9, while I was grazing in the valley about 500 meters from Mitzpe Yair, I became the victim of this danger. The bullet shot by the settler entered my lower stomach, tearing my intestines out. I stayed on the ground, still conscious, until nearby shepherds rushed to carry me on their donkey toward the nearest road that the ambulance could reach. It took two hours, while I was bleeding with my intestines falling out of my body, before I was in the ambulance heading to the hospital.

For nearly a year after the settler’s bullet entered my body, I lived in the intensive care unit. I went from hospitals in Be’er Sheva, to Bethlehem, to Jordan, and finally to Iraq, before doctors were able to build plastic pipes inside me that could replace my destroyed intestines.

This bullet changed my life entirely. For the past 21 years I have been in constant pain, and need regular medical examination and monitoring of my intestines and kidneys. I am no longer able to work with the strength that I used to, but have no choice but to continue; my children and grandchildren rely on my labor to sustain our family.

My family continues to risk our lives everyday when grazing our sheep, knowing we could be subjected to violent settler attacks at any moment. To this day, Mitzpe Yair is expanding, taking more and more of our land every year.

Mahmoud Awad

I was young when the doctor told me that my organs were not working properly. “Your body is operating at 65 percent,” they told me. By the time I was 32, I was suffering from three chronic illnesses and was bedridden from the pain of my kidney and gallbladder stones.

On March 21, 2011, the pain had gotten so unbearable that the doctors called me in to surgery to remove my gallbladder. I left my village of Tuba that morning on my donkey, and set out on the 23-kilometer journey to Yatta, the closest city where we can access medical services.

For the first half of my life, the commute to Yatta was along a three-kilometer road. But in the early 2000s, settlers from Ma’on began to build an extension to their settlement, an illegal outpost that they named “Havat Ma’on.” The residents of Tuba were officially banned from using our road in 2002, when my brother Ali was brutally attacked on his tractor while on his way to Yatta to get water for our village. For the past 20 years, our commute to Yatta has been slow and dangerous, as we take the long hilly roads around Havat Ma’on.

I was about an hour into my climb over the mountains toward Yatta when I started to hear running footsteps behind me. I turned my donkey around just in time to see a masked settler coming toward me with a knife in his hand. He went straight for my chest; I assume he was aiming for my heart. He stabbed me twice before I was able to get away. I fell to the ground and yelled for help from the nearby village of A-Tuwani.

My body is not like any other normal human; I have been in pain since my mother gave birth to me. The settler’s knife punctured my lung, and the internal bleeding from it left me in the intensive care unit for 10 days. I thought I was going to the hospital that day to ease some of the pain in my body, but instead, it was five months before my body was stable enough for the doctors to proceed with the operation on my gallbladder. It took two years until I was able to work again.

Harun Abu Aram

My name is Harun Abu Aram. I am 25 years old and I live in a paralyzed body in the village of Al-Rakeez in Masafer Yatta. On the first day of 2021, the Israeli occupation turned my life upside down.

I used to be an energetic young man. I loved working in construction and with our family’s livestock. I was engaged and planning to get married by the age of 24. By the end of 2020, I had saved enough money to build a small house for me and my fiancée to live in. But only two weeks after it was completed, the Israeli army came to demolish it and everything I had worked so hard to earn.

At the beginning of 2021, less than a month after my home was demolished, the army returned to Al-Rakeez to confiscate a generator from my neighbor. As his only source of electricity, he was scared to lose it. I stood with him, defending the generator, and that’s when it happened. One of the soldiers took out his weapon and shot me in the back of the neck.

The bullet passed through the top of my spinal cord, immediately paralyzing my entire body. For four months I stayed in Ahli Hospital in Hebron. Everything that my body needed to survive was provided by machines; I was hooked up to breathing and eating tubes. After those months, the doctors said to my mother, “We cannot do any more for Harun, prepare a room in your house like a hospital room, buy a respirator and take him home.” Before I left the hospital, my fiancée came to sign our divorce papers and say goodbye to me.

Since November, I have been back in Al-Rakeez, living in a cave with five of my family members who take care of me. Being here, my body and mind continue to fall apart. The bed sores that are covering my back and legs are getting bigger every day.

I avoid sleeping at night because of the nightmares; I cannot stop seeing the soldier’s face whenever I close my eyes. And so often, I wake my family up in the middle of the night from all my screaming. I am in so much pain, especially when I am cold, it feels like I have been struck by lightning. This pain has become a daily routine for me and my family.

I always dreamed of having a family of my own. To raise more goats, to be able to work and make life easier for my parents. But now, my 14-year-old brother is working in construction to support us with the costs of all my treatments. I lost all of those dreams with a single bullet, and now my family is working just to keep me alive.

Sami Hureini

It was a nightmare. And it all happened so fast. I looked down and my shoe had flown off and my foot was blue. My lower leg was bent, the part that is supposed to be straight. From the moment I saw it, I fell to the ground. The pain was gradual, but it got more and more intense as I waited over an hour for the ambulance to arrive. The Israeli police, who we called immediately after the settler hit me, were there the whole time, watching.

That day, the settler had been circling us on his ATV all afternoon as we were working in the cave. It was March 2018, I was 20 years old and was helping to repair the village of Sarura in Masafer Yatta. The families of Sarura had trouble living on their land due to an increase in settler violence. So my siblings and friends started the activist group, Youth of Sumud, with the goal of developing a place in the village for the families to live in. We had been working in Sarura for less than a year when the settler ran me over, breaking my leg in three places.

For months after the attack, I was in bed, lying on my back. The doctors told me not to move so the bone could heal. I’m one of those people who likes to move. I have always been this way. So when this happened, and I couldn’t leave my bed, it really messed with me psychologically. I just kept thinking about the settlers, and how there was no punishment for them. That they would just keep going out, free, with no one to stop them.

Growing up under occupation, I have always known that there is no accountability for settlers. But even so, after I was the target of their attacks, I still had some small hope that they wouldn’t get away with it — that something would happen to them for what they did to me. But now, four years later without justice, this hope doesn’t exist anymore.

The scars on my leg don’t just remind me of the day I was attacked. They now mark all of the violence that my community has lived through.

In January 2021, Harun Abu Aram was shot in the neck, and a few days later, the army arrested me for participating in protests to demand justice for him. We filed a complaint to the police against the settler, but the file was closed before reaching the court. When our lawyers tried to reopen it, it was closed again, claiming there was insufficient evidence — even though the whole incident is on video.

For me, these incidents felt connected to my scars — I knew all of it was part of the same violent system that destroyed my leg. Sometimes, I can almost forget about all of the things that we live through every day. But this scar is a permanent reminder.

Mohammed Makhamreh

I used to be a very energetic and healthy young man. As the only son in my family, I held a lot of responsibility to work hard and help my family live on our land. Especially as a community of shepherds and farmers, our livelihood is centered almost entirely around hard physical activity. But now, all of this physical labor is only a source of stress for me and my family, ever since the day my hand was blown off by the Israeli army.

On January 8, 2021, I was feeding our sheep and getting ready to go to Yatta to meet my father. Just as I was bringing the flock into the barn, I tripped on something and fell down. The next thing I remember is waking up in the hospital covered in injuries. I had already undergone surgery on my chest and leg, and when I looked down at my body I realized my right hand was gone.

I found out later that I had fallen onto an unexploded grenade that day. The army, which uses my village for military training, sometimes leaves its weapons on our land. I was lucky that my neighbor was close enough to hear the grenade explode and was able to get help and rush me to the hospital. If he hadn’t been there, I really think I might have died that day.

The Israeli army declared my family’s land a firing zone long before I was born. My whole life, they have been training their soldiers inside our village. They shoot in our fields, just over 100 meters from our homes. They drive tanks over our caves and wheat fields, leaving our crops damaged. This time, they left an unexploded weapon that changed my life forever.

Now that I live my life with only one hand, all the work that I used to enjoy is only a source of stress and brings a feeling of powerlessness. We have to ask the neighbors to assist with all the work that requires two hands, like shearing our sheep’s wool when the summer comes. But the worst is the psychological pressure I feel every day, as I try to live my life and support my family with a missing hand.

Mohammed Hamamda (as told by Sohaib Hamamda)

We were all huddled together, 24 people in one room, hiding from the swarm of settlers that were running into our village and smashing everything in sight. It was then that I noticed Mohammed wasn’t with us. I rushed to the room that we put him to sleep in and there he was, lying on his mattress, unconscious in a pool of his own blood.

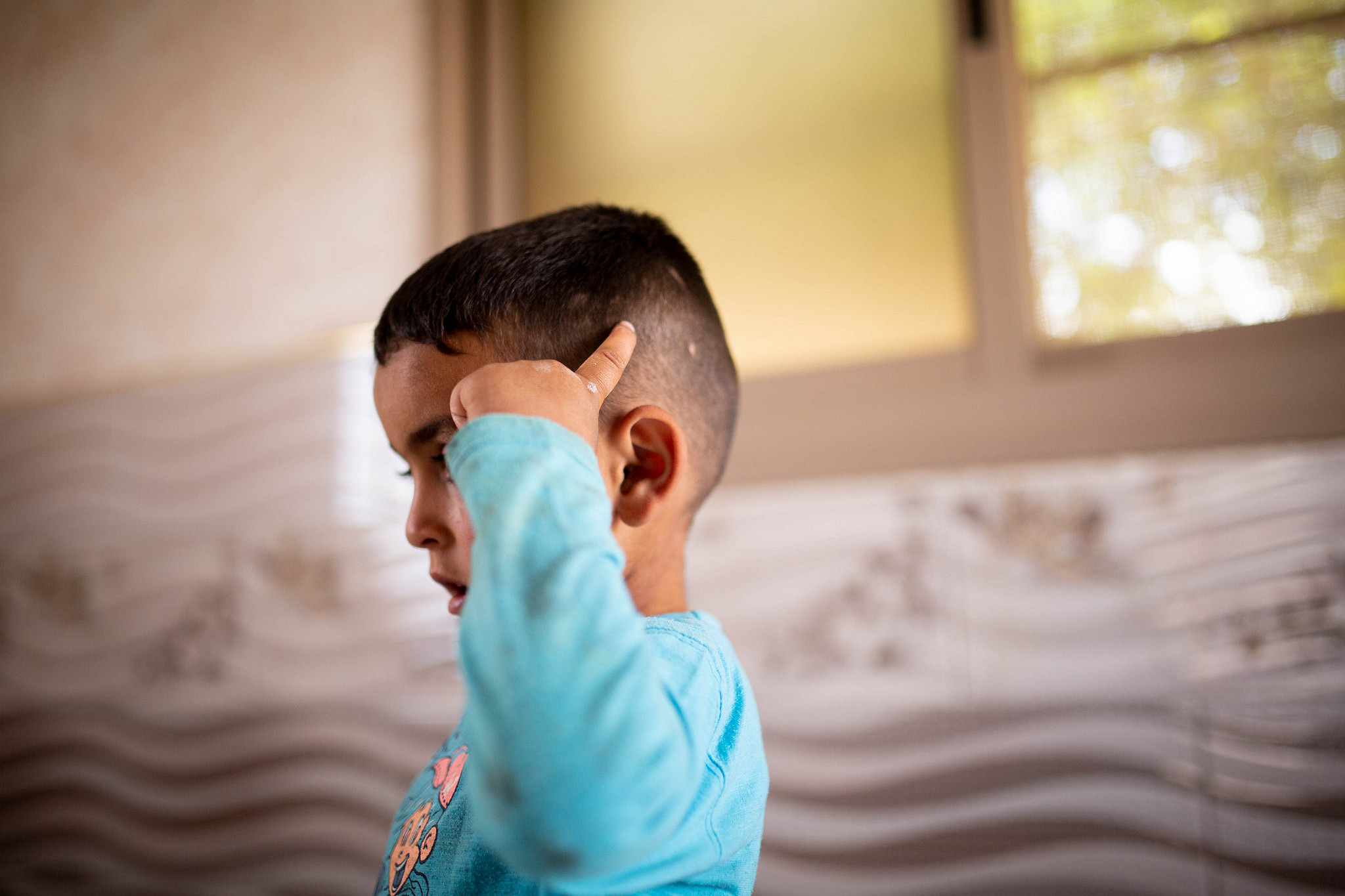

My name is Sohaib Hamamda and I am 24 years old. Last September, I carried Mohammed, my four-year-old nephew, to the ambulance at the end of our road during a settler attack on my village, Mufagara.

The settlers had fractured his skull while he was sleeping in his bed, with a large rock that they threw through his window. While I carried him, the settlers smashed the windshields of our tractors, punctured our water tanks with knives, flipped our cars over, and hurled rocks at our solar panels. All the while, the army stood by, tear gassing us Palestinians.

The young settlers of Havat Ma’on and Avigayil did this to Mohammed on Sept. 28, 2021, while they were celebrating the Jewish holiday of Simchat Torah. That day, they first came into our village dancing and singing, and then began to violently wreak havoc on our lives. This day was a nightmare for us all, but the scars that Mohammed has on his head will affect him for the rest of his life.

Today, Mohammed cannot play with his friends in the village like he used to. Running and jumping makes his head hurt and he quickly becomes dizzy. We regularly take him to the hospital for testing, as it is still unclear what the long-term effects are of the fractured skull and internal bleeding that Mohammed suffered that day.

Correction, July 28, 2022: An earlier version of this article stated that Yitzhak Rabin gave an order to break Palestinian protesters’ bones in 1987. He gave the order in January 1988.