Soon after the Palestinian Authority put the cities and towns of the occupied West Bank under COVID-19 lockdown in late March, Amer Abu Hijleh received a call from a fellow farmer telling him that Israeli settlers were working his land.

Abu Hijleh, 56, hung up and immediately left his home in the village of Deir Istiya, and drove toward his land, located in Area C of the West Bank next to the Israeli settlement of Yakir. Upon arrival, Abu Hijleh discovered that settlers had begun digging a hole in the ground after uprooting some shrubbery.

A few minutes later, Israeli forces and settlement security guards arrived at the scene and asked Abu Hijleh and a few Israeli activists who had come to support him to evacuate the area. “When I told [the security forces] that settlers had been working in my land, they didn’t stop them, and instead asked me to bring my documents [of land ownership] and contact the Israeli Civil Administration,” Abu Hijleh said, referring to the department of the Israeli Defense Ministry that administers the occupation in the West Bank.

Two weeks later, after collecting all the necessary documents showing he had inherited the plot from his father, Abu Hijleh returned to his land and found that the settlers had turned the hole in the ground into a pool. “Why are you angry? It’s just a pool for our children,” an Israeli settler reportedly told Abu Hijleh before representatives from the Civil Administration arrived and asked both the Palestinians and the settlers to evacuate “until the issue is legally resolved.”

“I couldn’t trust the Israeli Civil Administration and returned to inspect the land 10 days later,” Abu Hijleh said. “I found a finished pool with some chairs. All their work was completed.”

Abu Hijleh then got in touch with the Israeli human rights organization Yesh Din, in order to start building a legal case. Meanwhile, he planned to continue cultivating his land by planting olive trees. But when he arrived, the Israeli army denied him access to the area, he said.

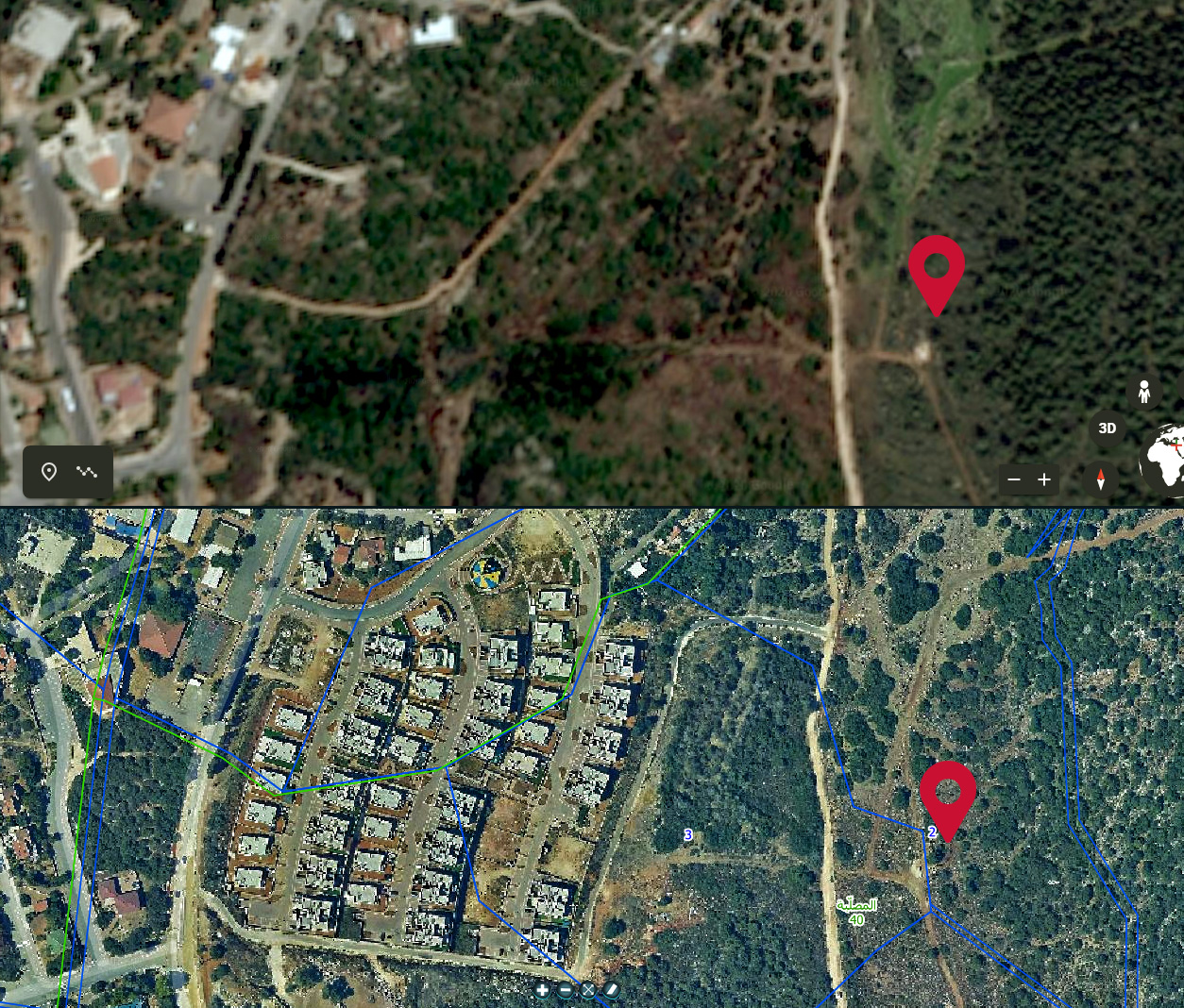

In early July, +972 Magazine visited the location alongside Abu Hijleh and his son. The area near the pool was littered with cement bags, remains of a campfire, and pipes. A few meters away, more cement bags were stored behind the settlement’s security fence gate, which Abu Hijleh sees as evidence of that the Israeli local council was involved in the building of the pool. With Yakir growing east, he is worried this could be the beginning of a settlement expansion process that will cost him his land.

Fadia Qawasmi, an attorney and field investigator with Yesh Din, confirmed that the organization asked the Civil Administration to remove the pool after reviewing all of Abu Hijleh’s documents.

Settlements grow while Palestinians can’t build

In 1981, Israeli authorities confiscated around 700 dunams of Palestinian land to build the settlement of Yakir. The plan included the 82-dunam plot that belonged to Abu Hijleh’s father, but luckily, the family succeeded in holding onto their land. “The affected [people] own their land and have inherited it from their grandparents. The reason for the confiscation is to expand Yakir,” reads a 1982 newspaper stub published by Al Quds, which Abu Hijleh still keeps.

Since the 1980s — following the Israeli High Court’s ruling in the Elon Moreh case, which prohibited the construction of civilian settlements on private Palestinian land — Israeli authorities have enabled settlement expansion by requisitioning Palestinian land and declaring it as “state land.” Though Palestinians make up about 86 percent of the West Bank’s population, over the past four decades, the Civil Administration has allocated less than one percent of state land in the West Bank to Palestinians, according to data obtained by Israeli settlement watchdog Peace Now.

The land next to Abu Hijleh’s plot includes areas that were expropriated and turned into a military firing zone. “My neighbor lost part of his land because [Palestinians] cannot legally object to expropriation for military purposes,” he said. Abu Hijleh indicated that there is an Israeli water facility on his land that provides Yakir with Palestinian groundwater. “I couldn’t object to that as well because expropriations for public services are allowed.”

Abu Hijleh’s land, which will likely be included in Netanyahu’s annexation plan, is located just outside the Wadi Qana nature reserve, a mostly Palestinian-owned area surrounded by five settlements, one of which is Yakir. Residents claim that settlement outposts are expanding on the hills overlooking the valley, while Palestinians are not allowed to build on their land.

In Area C, which is under full Israeli administrative and security control, obtaining a building permit is almost impossible. At the same time, Israeli settlements continue to grow across the West Bank. According to the United Nations, Israeli authorities have demolished 320 Palestinian structures across the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, since the beginning of 2020, affecting 1,578 people.

“I’m waiting to see what will happen in July regarding Netanyahu’s annexation plan,” Abu Hijleh’s said, adding that he fears Israel will implement the Absentee Property Law — passed in 1950 to legalize the takeover of Palestinian land left by refugees during the Nakba — in the West Bank. The law is still being used in East Jerusalem, which Israel annexed in 1967, to dispossess Palestinians in the city, although it is yet unclear whether it will be used in the West Bank as well.

According to Yesh Din, in the best-case scenario, Israel will demolish the settlers’ pool. After that, Abu Hijleh will still be able to visit his land but will not be able to build on it — unlike the settlers.

+972 Magazine reached out to the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT), a unit of the Israeli Defense Ministry that oversees the occupation in the West Bank, which said that the case was “known to the Civil Administration. Enforcement in the area will take place in accordance with the authorities and procedures and will be subject to operational priorities and considerations.”

A version of this article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.