Netanyahu knows that even in 2016, Mizrahim have the ability to kick him out of power.

Benjamin Netanyahu has seen better weeks. Between being strong-armed by members of his cabinet over the confirmation of Avigdor Liberman as defense minister, and the fact that his wife, Sara, may soon be indicted over her unscrupulous handling of the prime minister’s households, the past few days have been rough. But amid the turbulence, Bibi was able to find a golden calf and, true to form, milk it for all its worth.

On paper the story seems both simple and innocuous: early last week Netanyahu announced that his brother, Ido, had taken a D.N.A. test, according to which the Netanyahu family can actually trace its roots back to Spain. Thus, Netanyahu implied, Israel finally had its own (at least partially) Sephardic prime minister.

Until that moment, Netanyahu was thought to be of Ashkenazi (Eastern European Jewish) background, just like every single other prime minister who preceded him. This point cannot be overstated: whether they have come from the political right or left, Israel’s heads of state have all belonged to the same ethnic group (often referred to as “the white tribe”) — one which is credited with forging Israel’s founding myths, forming the political and military establishments, and dominating the country’s cultural life. In order to understand the significance of Netanyahu’s declaration, however, we need to understand how ethnicity became an essential component in Israel’s culture wars.

In the first years following the state’s formation, MAPAI (the precursor to today’s Labor Party) led by Prime Minister David Ben Gurion, did just about everything it could to ensure that Mizrahim (Jews from Muslim or Arab countries, sometimes referred to as Sephardim, or Sephardic Jews) were materially and culturally marginalized. Contrary to the image of a free, democratic state that Israel peddled to the world, Mizrahim encountered an authoritarian state that sought to keep them ghettoized and politically impotent. North African immigrants were sprayed with DDT upon their arrival, hundreds of Yemenite babies were disappeared and sometimes given up for adoption to Ashkenazi families, Mizrahim were forced into exploitative, menial labor, large numbers were directed upon arrival to far-flung development towns that quickly became slums, and any attempts at revolt (and there were attempts) were brutally put down by the state.

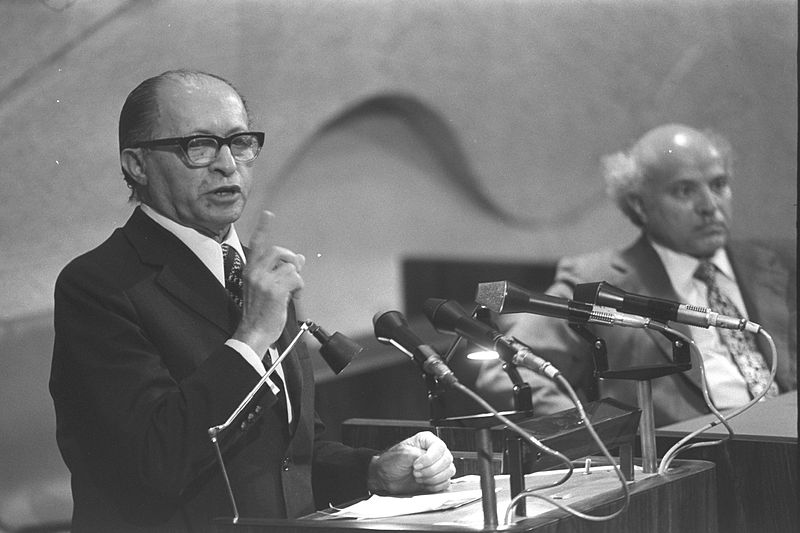

In 1977 Likud leader Menachem Begin changed all that. Begin, who throughout the first years of the state led the opposition, was the first major Israeli leader to take seriously the plight of Mizrahim. An Ashkenazi who was until then considered the perpetual underdog of Israeli politics, Begin gave impassioned speeches against Labor’s corrupt, discriminatory policies — solidifying a Mizrahi voting bloc that now had a political home to beat back those who treated them as second-class citizens. That year Mizrahim catapulted Begin into the office of prime minister and have helped keep Likud in power for much of the last 40 years. (It should be made clear that Mizrahim vote for nearly all parties in Israel, yet Likud has historically been the major bastion of Mizrahi political activism).

Labor, on the other hand, did very little to atone for its transgressions, and continues to pay for it. In fact, for years to come the party only doubled down on its treatment of Mizrahim. During the 1981 elections Mordechai “Mottah” Gur, former IDF chief of staff, spoke to a seething crowd of Likud supporters who nearly overran what was supposed to be a Labor (then called “Alignment”) campaign rally in Beit Shemesh. Glaring from the podium at a crowd chanting “Begin! Begin!” Gur deployed his most patronizing tone and in one sentence inadvertently summarized the history of Israel’s Ashkenazi rule vis-a-vis the country’s minorities: “Just like yelling didn’t help them [the Arabs] and we screwed them; yelling won’t help you and we’ll screw you too.”

Mottah Gur’s speech at a campaign rally in 1981:

If anyone understands that Israel’s intra-Jewish ethnic conflict didn’t end in 1981, it’s Netanyahu. Israeli legend has it that many Mizrahim refused to believe Begin was not himself of Moroccan origin. Netanyahu is exploiting this trope at a time when Ashkenazi members of Labor are attacking one of the party’s sole Mizrahi voices for proposing a law that would do away with admissions committees, which accept or reject housing applicants based on their “social suitability” and whether they fit into the communities’ “social and cultural fabric” (activists have for years complained that these committees are being used as a legal mechanism to reject Mizrahim, Palestinian citizens, Ethiopians, and others from living in places such as kibbutzim, which have historically formed the basis of the Labor movement’s political power). More recently, in 2006, Labor voters chose Amir Peretz, who is of Moroccan origin, as their leader and candidate for prime minister. However his failure and eventual loss of control of the party seemed like an omen that Labor could never truly accept a change of identity.

Netanyahu knows that even in 2016, what is often referred to as the “ethnic genie” is alive and well — that Mizrahim still have the power to decide elections, as they did back in 1977, and that it’s never a bad time to try shoring up his support among the voting bloc.

Why does this matter? Well, first of all it shouldn’t. Political leaders should be evaluated based on their performance, not where they come from. But in Israel, as in in other countries, the politics of ethnicity is bound up in an ongoing culture war between the new elites and those of yesteryear. The fact that the prime minister of Israel is now claiming Mizrahi/Sephardic identity is a sign of a sea change: if Mizrahi identity and politics were once scorned by the elite, today they carry with them a certain amount of political capital.

For Netanyahu, this might mean just another card to play as he focuses on what he does best: surviving yet another tumultuous political moment. For Mizrahim, however, it could mean the beginning of a political ascension that no longer depends on Ashkenazi benefactors, whether from the Left or from the Right.