The feeling one gets after visiting Umm Al Khir is one of shock: do you insist on stealing even this little bit?

By Yesh Din, written by Yossi Gurvitz

At the beginning of January, in the company of Yesh Din’s field researcher Muhaned Anati and field operations coordinator Yudit Avidor, I visited the village of Umm Al Khir. The reason for the visit was an attempt to understand what it is about this place that draws so much violence. We have been following the incidents in Umm Al Khir since 2010; we have 13 cases. Twelve deal with settler violence and one with violence at the hands of the security forces.

Umm Al Khir was built in the 1960s, prior to the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, by Bedouins expelled in 1948 from the Tel Arad area. Since the occupation of 1967 onwards, the Israeli government has willfully neglected Umm Al Khir. It sits in Area C, which is under full Israeli control, both civil and military (as opposed to Areas A or B). Area C is also where, should the Bennet Plan be implemented, would be annexed to Israel. One could assume, then, that Israel will make certain the region is developed to the benefit of all its inhabitants.

Then again, when you assume you make an ass out of you and me.

* * *

Umm Al Khir recently made headlines after someone – a tracker found footprints leading to the settlement of Carmel – poured water on the local taboun (a traditional baking oven) and put it out of order. We’ve written about it here. The taboun of Umm Al Khir made it to the the High Court of Justice after the Civil Administration wanted to demolish it.

I expected, then, to see an impressive, imposing structure. Intellectually, I knew it was made of mud and straw, yet I had some expectations. This is how it looks:

In the background of the taboun you can see the settlement of Carmel. Suleiman, one of the leaders of the village, told me of a Bedouin saying: “the wind, water and bread – without these, a man cannot live.” The taboun serves the needs of Umm Al Khir’s residents: without it, there would be no bread.

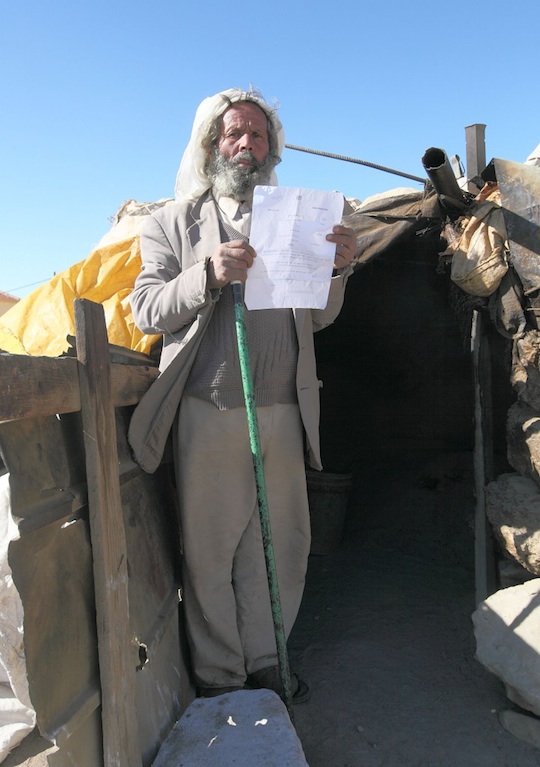

The document Suleiman is clutching is a High Court decision from 2011, following a petition filed by the residents, forbidding making any change to the taboun until another decision is made.

There are about 150 residents in Umm Al Khir, and the taboun supplies them with bread. A taboun must be fired at all times. Basically, it is a pit filled with embers of animal dung that is fed daily. For as long as the taboun is fired, it maintains a steady level of heat. If it is doused with water, the pit must be emptied, cleaned, filled again and fired again; the taboun needs about 36 hours to reach its steady level of heat. The meaning of dousing it is that a group of people, who already have little, are left without bread for two or more days.

The residents told us that they suggested turning off the taboun, the smell of which settlers of Carmel complain about – if the army would, in return, make certain that they receive a daily bread supply from the relatively nearby Hebron bakeries. They did not receive an answer.

But the taboun is not the issue. At best, it is the pretext.

The story, as it seems, is the one we know from other cases in the West Bank: that of annexation and ethnic cleansing. The story is about the lust for land, about a military-settler-government-legal complex, intended for the dispossession of people who have little by people who have too much. After all, if the people of Umm Al Khir are left without bread, if their oven is extinguished, they would have no choice but to leave. And then the residents of Carmel could take over their land, which is so close, almost at the end of their fingertips.

We used to call it a quiet transfer.

Examined from this angle, the behavior of the Israeli civilians who harmed the taboun should not surprise us – and the behavior of their collaborators in the Israeli government is even less surprising. This is the same modus operandi of the illegal settlements, as presented in Yesh Din’s report about Adei Ad, The Road to Dispossession: making life intolerable for the Palestinians until they flee. The newly vacated land will, in time, be taken over by Israeli civilians.

For the residents of Umm Al Khir the wilderness depicted above is home; it is all that there is. And the government of Israel, which twice invaded their land, will not leave them even that much.

In your names; in mine; with our tax money; by the young men we sent to the army, turned into jackboots.

Written by Yossi Gurvitz in his capacity as a blogger for Yesh Din, Volunteers for Human Rights. A version of this post was first published on Yesh Din’s blog.