The idea that the tough choice about settlers can somehow be waved away through the magic wand of land swaps is a fantasy. Any solution that will leave most settlers in place (in one state, or two states) will be just a perpetuation of the conflict under another title.

Following the uproar in the United States and Israel about his comments regarding 1967 borders, Obama, in his speech to AIPAC last week, stated

… since my position has been misrepresented several times, let me reaffirm what “1967 lines with mutually agreed swaps” means. By definition, it means that the parties themselves – Israelis and Palestinians – will negotiate a border that is different than the one that existed on June 4, 1967… [this formula] allows the parties themselves to account for the changes that have taken place over the last forty-four years, including the new demographic realities on the ground and the needs of both sides.

This response rebuts critics, who have falsely claimed that Obama insists on a return to 1967 borders, and makes clear that Obama himself support changes to those borders. The crux of the matter appears to be the “swaps,” which are the sum of the difference between the 1967 borders and the modified borders that Obama (and many others) have in mind. To understand the debate on this issue, therefore, one must first understand the rationale and purpose of the swaps idea.

The main dispute about the border between Israel and a future Palestinian state concerns the Jewish settlements in the West Bank, with a population of roughly half a million people, of which about 200,000 live in areas surrounding Jerusalem, unilaterally annexed by Israel, and the rest spread throughout the Palestinian territories.

Israel wants to evacuate as few of these settlers as possible, whereas the Palestinians want to keep as much as their territory as possible. This is where the swaps come in: Israel will annex lands holding the majority of the settlers, thus reducing the amount of people evacuated, and the Palestinians will be compensated with other territories, which are within Israel’s internationally recognized borders, thus allowing them to keep the same amount of land.

On the surface, this appears to be a neat solution, and, in fact, the principle of land swaps has been largely accepted by both sides. The differences seem tiny: According to the Palestine Papers, in 2008, Israel offered land swaps amounting to 6.3 percent of the West Bank area, the Palestinians countered with 1.9 percent, and negotiations fell apart at this point. The West Bank is extremely small, smaller than three quarters of existing sovereign countries. The land area in dispute amounts to less than 250 square kilometers, or about 60,000 acres.

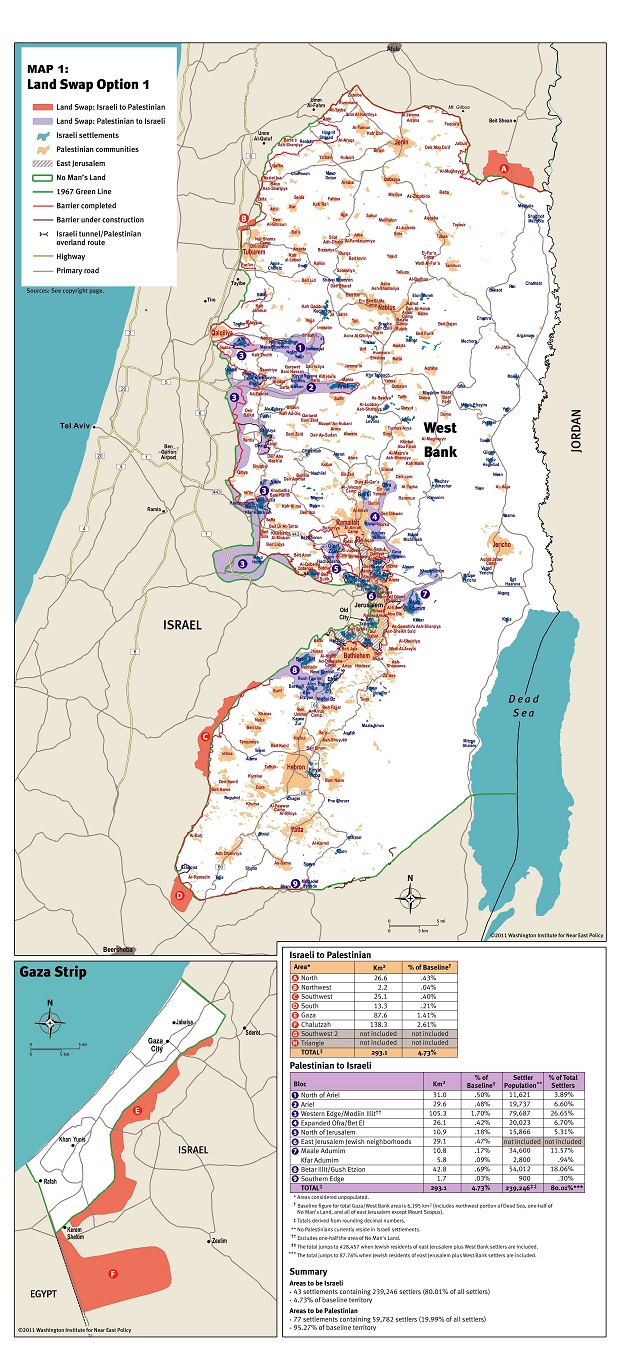

But what is truly at stake in the issue of borders is not the amount of land that is to be exchanged, but its geographical distribution. To see why, one need only look at a map created by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, a moderate pro-Israeli think tank (h/t to Matt Yglesia).

The map, which lies between the Israeli and Palestinian proposals in 2008, looks like someone spilled (purple) ink on it. It portrays a variety of narrow strips progressing from Israel into the heart of the West bank, complemented by Israeli blobs, surrounded by Palestinian territory, and connected to Israel proper only through slender, fragile looking bands. Moreover, there are lots of these spots – nine, to be exact.

This would not be a problem if the relationship between Israelis and Palestinians was based on mutual trust and friendship. Borders would be open, people would move across Israeli and Palestinian territories without feeling the difference, and the fact that your town is Palestinian or Israeli would matter for issues such as government services, voting in elections and questions of symbolism.

But this is not the situation envisioned by those who suggest land swaps. Indeed, part of the reason the map looks so strange is precisely because it is premised on total separation of movements. The strips are so narrow, winding, and strangely shaped, because the map makers attempted to ensure that both Israeli and Palestinian territory are “contiguous,” by which they mean that Palestinians would be able to move between Palestinian areas without entering Israel, and vice versa.

Even with total focus on this consideration, they fail in the task:

… the contiguity issue is particularly complicated in the areas surrounding Jerusalem because settlements annexed to Israel will need to maintain a direct route to the city without precluding the contiguity of Palestinian north-south transportation or access to east Jerusalem. These traffic flows can be maintained with existing overpasses and tunnels, the construction of a few new roads, and a degree of creativity.

The insistence on contiguity (up to the absurd “vertical” division of sovereignty, with one side claiming the tunnel and the other claiming the overpass directly on top of it) stems from the fact that Israel will not allow Palestinians to freely pass through its territory; nor are they willing for their citizens to rely on movement through Palestinian territory. Non-contiguity becomes complete disconnection under these circumstances.

As Shakespeare said, “This was sometime a paradox, but now the time gives it proof.” If there is no free movement, there must be contiguity. However, in order to achieve contiguity, one must create borders which are so convoluted and elongated, that even the slightest incident could paralyze movement completely. Considering the balance of forces, it is far more likely that Palestinian movement, rather than Israeli, would be cut off.

That is why the Palestinians could not accept the Israeli offer in 2008, nor the option presented by the Washington Institute. It is not the amount of land that is problematic, but the impact of borders on movement within Palestinian territory. The past decade has demonstrated the devastating impact of such cutoffs from land and free movement for Palestinian lives, and anything that perpetuates this situation would just be a continuation of the conflict, even if some leaders sign on some dotted line.

What is the alternative? Some say, a one-state solution. Of course, right now, there is only one state between the Jordan and the Mediterranean Sea, and Palestinian movement is still hindered. Maybe if Israelis could be pressured to give the vote to millions of Palestinians, that will change. But surely, there is a solution that Israeli would find far easier to accept than one democratic state.

In other words, why not evacuate more settlers? The Washington Institute provides the answer mandated by conventional wisdom:

No Israeli administration could evict a large majority of settlers—the prospects for social unrest would be too high, as presaged by the problems accompanying the much more modest Gaza disengagement in 2005…

This argument is strange on two levels. First, the most generous scenario presented by the Institute would still require the eviction of 60,000 settlers. But they reject the solution proposed by the Geneva initiative, because it would require removal of 130,000 people. So, Israeli society would survive the eviction of less than 1% of its population, but would collapse if barely 2% had to move? The Washington Institute (or, for that matter, any other pundit I have read) fails to explain the rationale behind such distinctions.

Second, there are clear indications that the difficulty of evacuating settlers is overstated. The Gaza evacuation was traumatic for the settlers and the hard right, less so for the nation as a whole. And it was conducted as a unilateral move, with hazy and dubious benefits, not as part of a comprehensive deal to end the conflict. Moreover, the problem of evicting Gaza was not the size of the population which had to be moved. It was only marginally more difficult than the evacuation of some tiny outposts.

The resistance to the evacuation of the settlers does not stem from their numbers, but from ideological and nationalist sentiments. Israelis finds it very hard to move Jews in order to make room from Arabs, when their entire history is based on the reverse dynamic. When displacement occurs on a large scale in a different context, this is much less of a problem.

This is, after all, a country that absorbed half a million immigrants, a 70 percent increase in its population, in just two years (1948-1950), when it was much poorer than it is today. It the 1990s, it absorbed a million immigrants from the former Soviet union, or about 20 percent of its population. In both cases, almost none of the new immigrants spoke Hebrew or had any familiarity with Israeli society. So 70 percent or 20 percent completely new immigrants is possible, but 6-7 percent (all of the settlers in the West Bank, including Jerusalem) of people who are already well-integrated in society would be impossible?

One may argue that this is technically possible, but politically impossible. Once again, I disagree. Let us compare this to the return of Palestinian refugees into Israel (not the right of return, or symbolic return, but actual, massive return of millions of refugees). Almost all Jewish Israelis believe that this will lead to Israel’s destruction, and their own, personal physical destruction. Right or wrong, that is what they believe, and that belief will not change in the foreseeable future.

No such belief holds for the mass evacuation of settlers. Surely, right now, opposition to this scenario is almost as high as opposition to Palestinian return. But the factors shaping the two positions are different. Resistance to mass settler evacuation stems from the belief that it is an unnecessary concession, a pointless pain. Israelis believe, and this belief is reinforced by opinion makers in Israel and abroad, that most settlers can stay in place in a future agreement. So why evacuate them?

This belief may change, if the assumptions underlying it are undermined. If Israelis have to choose between perpetual conflict with the Palestinians combined with international isolation, on the one hand, and evacuating most of the settlers, on the other hand, they may yet choose the first option. But it will be a tough choice. Not so with Palestinian return. Choosing between conflict and isolation, and one’s own demise, is an easy choice. The first option will always prevail.

Right now, of course, Israel is faced with neither choice, and it may be able to go on as it is for a long time, maybe even forever. But the idea that the tough choice about settlers can somehow be waved away through the magic wand of land swaps is a fantasy. Any solution that will leave most settlers in place (in one state, or two states) will be just a perpetuation of the conflict under another title. Perhaps that is what is in store for us. But let us not kid ourselves about the implications.

+972 magazine needs your support. check this post to see why, and how can you help to keep this project going