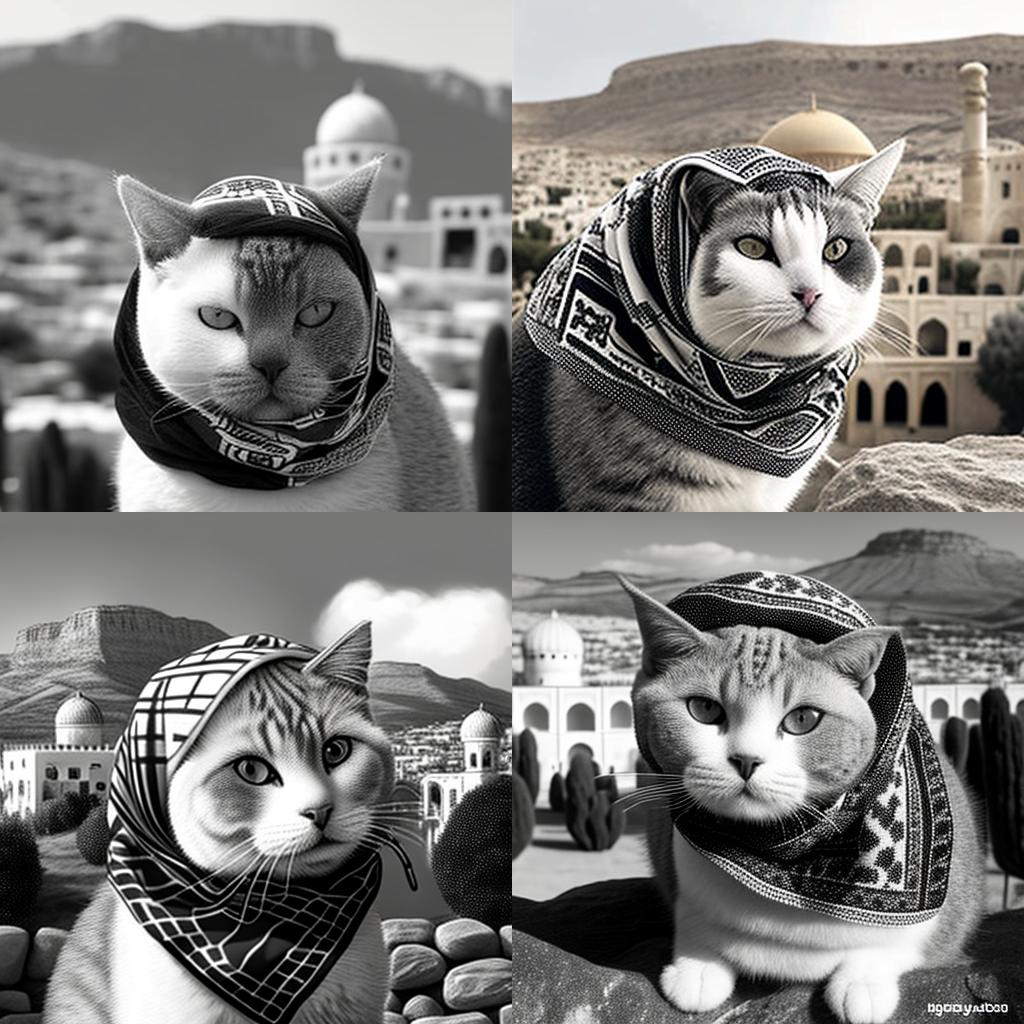

Recently, as part of an ongoing project examining Palestinian digital rights and narratives in emerging online spaces, I decided to explore Palestinian representations of place in a popular text-to-image AI generator. After prompting the AI program to generate images of a cat wearing a Palestinian keffiyeh in front of holy sites in Jerusalem, I realized a few clicks in that I was navigating a landscape of opaque biases within the program.

The AI struggled to replicate its characteristic fishnet pattern, but understood the keffiyeh as a scarf wrapped around the head or neck. Clearly, the 100,000,000 images used without consent to train the generative AI were not enough to produce more than the most generalized keffiyeh.

More alarming is what happened when I used the same prompt but with the Dome of the Rock as the background. Suddenly, my AI-generated cat swapped its distorted keffiyeh for a headpiece resembling a hybrid ski hat/skullcap. I repeated the experiment several times with the prompts “Palestinian keffiyeh” and “Dome of the Rock,” and the generative AI consistently offered up a knitted skullcap instead of the vague keffiyeh. In contrast, this was not the case with “the Holy Sepulchre,” “the Mount of Olives,” and “the Old City,” against which backgrounds the program had no problem producing the vague keffiyeh.

As a Palestinian-American artist, I have grown concerned over the last few years with how high-tech tools can diminish human rights in digital spaces, reinforce the digital divide, or normalize surveillance technologies and lack of data protection. And this small experiment underscored how, for Palestinians, the adoption of popular generative AI tools means keeping track of and contesting new biases, discriminatory practices, and forms of erasure in an already skewed online landscape.

The different outcomes generative AI produces based on changing place names is just one example of how algorithmic and data bias can occur in AI systems. Large generative AI, such as ChatGPT, Midjourney, and soon Google’s Bard, are trained on massive data sets, often scraped from the internet in violation of internet users’ privacy. This data becomes anonymized and concurrently reinscribed with neutrality. A 2017 piece in the Economist argued that the world’s most valuable resource is no longer oil but data. Feeding machine learning’s tremendous demand for data has made unethically-scraped data sets the dirtiest and cheapest oil of the AI age.

Reproducing bias

To understand why my AI-generated cat keeps switching its head gear at different holy sites in Jerusalem, one must understand the indexing, categorization, and knowledge hierarchies underpinning AI systems. But public access to information about AI’s backend and processes is severely limited as companies keep AI in a black box with little regulation.

According to the EU’s 2021 regulatory framework proposal, popular generative AI is considered low-risk; by contrast, high-risk AI — such as that used in algorithmic policing, digital welfare systems, or facial recognition software — is defined as systems that interfere with people’s fundamental human rights, livelihoods, or freedom of movement. In the context of Palestine, examining low-risk AI more closely can offer some insight into dangerous AI already at work in Israel’s “frictionless” smart occupation, challenging the lack of regulation around high- and low-risk AI systems which are being rolled out without transparency, guardrails, and testing.

Nadim Nashif, co-founder of the Palestinian digital rights organization 7amleh, tells +972 that the automation of bias against Palestinians already exists on social media. Pointing to the disparate enforcement between Arabic and Hebrew content on Meta, which reached dangerous levels when hate speech against Palestinians intensified during the uprising of May 2021, Nashif describes a “vicious cycle” in which discriminatory takedowns of Palestinian content and under-moderation of Hebrew content “are fed into the machine which then starts taking down the content on its own.”

Discriminatory algorithms and biased feedback loops are already hazards of the current internet; as such, the discrimination and bias in new AI systems is fairly predictable. “If you ask Google,” Nashif explains, “[it will say] Jerusalem is the capital of Israel … it doesn’t say anything about the occupation [of East Jerusalem.]” The same, he notes, is true for Google Maps.

These biases carry over into AI. When I asked ChatGPT about occupied Jerusalem, for example, it used the phrase “disputed territory” and claimed Al-Aqsa is “contested.” This sounds more like the recent BBC coverage of the Israeli raid on worshippers in Al-Aqsa than something produced by a neutral, nonhuman agent. Failing to name illegal occupations or human rights abuses does not balance out the scales of justice; it only produces new political distortions.

A new kind of digital dispossession

The programming and data indexing that underwrite generative AI are not neutral; rather, they reinforce existing political and economic hegemonies. As Google whistle-blower Timnit Gebru warned, internet scraping and undocumented data mining produce an “amplification of a hegemonic worldview” which can “encode stereotypical and derogatory associations along gender, race, ethnicity, and disability status.”

However, unlike biases in other fields — the media, arts and culture, academia, etc — the type of bias that emerges from generative AI is without attribution or authorship. Almost too vague to be offensive, this loss of recognition and definition reveals a new kind of digital dispossession and dismissal of Palestinian narratives and lived experiences.

Dr. Matt Mahmoudi, a researcher and advisor on AI and human rights at Amnesty International, explains how digital rights exist within the matrix of human rights, noting that “there is no amount of de-biasing that can be done in the context of generative AI or other AI systems that would rid them of the particular political, economic, and social contexts within which they have been produced, and in which they continue to operate.”

Obscuring AI keeps the inherent biases in these systems from becoming legible, while claiming to be in public beta testing allows companies to avoid accountability. AI, Mahmoudi explains, is “effectively in perpetual beta, which means that it will always be able to shed responsibility [due] to it being not fully developed or not having enough data.”

Mahmoudi further points out that many generative AI tools have been trained on data sets from before 2021 — before Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and other prominent groups echoed long-standing Palestinian claims by adopting the term “apartheid” to describe the political regime in Israel/Palestine. “Would that information also be categorized by these generative AI systems, and would they return those results if someone were to go and look up the system or would [they] call [Israel/Palestine] contested?” he asks.

In other words, even if the situation changed radically tomorrow, generative AI would continue to mimic the mainstream discourse’s references to the occupation, and replicate the hegemonies of the internet until its programmers decided otherwise. Taking its data from the dominant internet, which repeatedly omits or skews Palestinian narratives and lived experience, apartheid is encoded in its DNA. Therefore, we cannot expect generative AI to create images or texts that do not replicate the current status quo under apartheid and occupation. This puts very real political and social limits on AI’s machine dreaming.

Debunking the myths of neutrality

To make AI fairer and more accountable, Mahmoudi explains, requires “extra labor where we then have to go do knowledge work that is about de-biasing the system, getting the system to represent the world correctly.” However, he warns, this creates “additional layers that must be peeled away before you get to the root cause of the issue, which is the international crime of apartheid in Palestine.”

Debunking the myths of neutrality in AI systems will be vital if they are to become increasingly ubiquitous. Though, as Mahmoudi notes, “the onus should be on people who want to roll out the technologies to prove why it’s necessary, not on us to prove why it shouldn’t be rolled out.”

To return to my AI-generated cat at the Dome of the Rock, its vague and confused keffiyeh might seem immaterial given the reality on the ground. However, the vagaries of these visual distortions — morphing into something that looks more like a knitted skull cap, yarmulke, or a ski hat than a keffiyeh — point to the obscurity of the data sets and the impenetrability of the backend that produces them. Does the AI categorize and rank the visual appearance of national-religious Israeli settlers at the Dome of the Rock differently than Palestinian worshippers at Al-Aqsa? Is one group over-represented in the data set? What visual cues does it score, including gender? Is it multilingual? Will we ever find out how this system works, or will it be perpetually shrouded in opacity?

Most read on +972

While confronting the unknowability of these systems is distressing in the case of low-risk AI, it can be potentially dangerous or even deadly in higher-risk systems. AI-powered surveillance systems, such as Clearview or BlueWolf, weaponize the machine’s capacity to detect patterns in image sets.

In Al-Aqsa, the Israeli police’s mass surveillance of the compound is ongoing through CCTV and drones. Palestinians in East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza are increasingly subjected to biometric surveillance and high-risk AI such as facial recognition technologies.

Under these AI systems, algorithms and surveillance data can be used to restrict Palestinians’ freedom of movement, assembly, privacy, and religion. With the intensification of powerful AI systems in the digital occupation and apartheid, we must ensure that Palestinian human rights are safeguarded even as they take on increasingly digital dimensions.