A new law in Poland criminalizing Holocaust-related speech presents an offensive, distorted narrative about the nation’s wartime history and its coming-to-terms with the past. But that’s far from the whole story.

By David Sarna Galdi

The Polish cabinet last month approved a law that will punish (including imprisonment) anyone for claiming that Poles killed Jews during the Second World War or referring to concentration camps like Auschwitz, which were located in Nazi-occupied Poland, as “Polish.” The legislation was met with widespread criticism, most of which missed the point; what’s most egregiously offensive about this law is its assault on storytelling.

The current Polish government, led by the far-right, nationalist, anti-abortion, anti-LGBTQ and Eurosceptic “Law and Justice Party,” has spent the year since its election sparking international condemnation for refusing to accept refugees, purging the ranks of the police and intelligence services, passing laws that inhibit the power of the judiciary, and dismissing inconvenient public broadcasting directors.

In February President Andrzej Duda announced his intention to revoke national honors bestowed on a Jan Tomasz Gross, a Polish historian who researched Polish complicity in the Holocaust. In July, Law and Justice’s education minister, Anna Zalewska, denied outright the well-documented participation of Polish citizens in Poland’s two most infamous pogroms against Jews.

Based on all of that anti-democratic flag-waving and previous attempts at repackaging Holocaust history, it’s fair to assume that the new law is designed to whitewash the story of wartime Poland and as a sword of Damocles hanging over free speech, “block attempts to reveal the truth about the murder of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust,” as Daniel Blatman wrote in Haaretz.

The Polish government is not alone; all communities and nations tell stories about themselves in order to create meaning. Indeed, all of history is a form of storytelling: “not a monument erected once and admired ever after,” as Rokhl Kafrissen wrote last month, “but an infrastructure tended” and “inevitably shaped by those who take it up.” Even renowned Holocaust historian Raul Hilberg, after writing his magnum opus, “The Destruction of the European Jews,” admitted that storytelling and poetry were tools to convey horrors that evaded normal language. I can express exactly why the Polish law is so offensive by telling my own story.

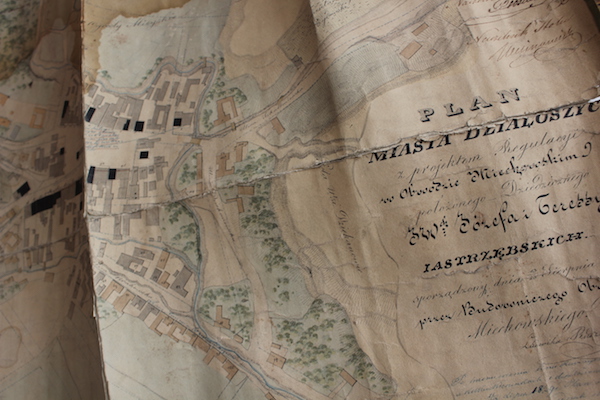

My grandfather, Joseph Sarna, one of six brothers, was born in 1921, to a simple, hardworking family in Dzialoszyce, a small town located an hour’s drive north of Krakow. Dzialoszyce was home to a majority of Jews (80 percent), making it a rich albeit small oasis of Jewish life, whose humble landscape was punctuated by a majestic synagogue, the skeleton of which still stands today.

When the Nazis arrived in Dzialoszyce in September 1939 my grandfather fled, was arrested, and spent the war in concentration camps. After liberation, his brothers returned to Dzialoszyce to find any surviving family. They were greeted, on the night of June 16, 1945, with the sound of gunfire and grenade explosions, as local Poles killed five Jewish returnees and injured dozens more. My family survived by hiding and fleeing their home a second time.

Much worse episodes occurred across Poland during and after the war; in 1941, in the town of Jedwabne, 340 Polish Jews were rounded up by their Polish neighbors, in coordination with the German Ordnungspolizei, and burned to death in a barn. In 1946 Polish soldiers, policemen and civilians killed 42 Holocaust-survivor Jews in the city of Kielce.

In January of 2014 I went to Poland to see my family’s hometown and search local archives. I was undaunted by the winter and opposition of my family. “HOW long are you staying there?!” asked my mother, as if it was inconceivable that anyone would want to spend more time in Poland than they would in a freezing shower. I rented an apartment in Krakow’s old Jewish neighborhood for two weeks. I wound up staying for more than a month.

I was doomed to be spellbound: raised on nostalgic stories of life before the deluge and my grandfather’s inexplicable survival in Krakow’s Plaszow Concentration Camp, made famous in “Schindler’s List.” I was walking with ghosts in a postcard-pretty landscape that, 70 years earlier, was my family’s crucible.

It felt like cheating, but I loved Krakow. I must’ve visited every church and museum. I procrastinated away whole afternoons beside the fireplace of an antique-stuffed cafe that hadn’t changed since 1939. I discovered the most sublime plum cake I’d ever eaten at a tiny bakery on Dominikanska Street. I didn’t mind the ankle-deep snow; it was an Instagram blessing. I sort of fell in love with Pawel, a blond, blue-eyed hipster from a small village, working hard to make ends meet while getting a master’s degree and dreaming of a career in art. He and his friends were of a generation of Polish millennials who post photos of artisanal baked goods to social media, devour H&M clothing and laugh about Poland’s obsolete reputation as a dusty post-Communist backwater.

When it came to anti-Semitism, what I found in Poland was surprising: I didn’t really find it. What I did find was the Krakow Jewish Center, where a busy schedule of events is a heartbeat of Jewish culture, raising awareness of the city’s Jewish heritage to its non-Jewish residents. In Warsaw I visited the Smithsonian-worthy POLIN Museum of the History of the Polish Jews, fresh out of the plastic. I became friends with Michal Pirog, a gay, Jewish prime-time television host whose tremendous popularity proved changing attitudes. In Dzialoszyce I was warmly welcomed by the mayor’s office and a local historian, who spent time showing me his research. I watched contemporary Polish films like “Poklosie,” “Ida” and “Demon,” which raise questions about Poland’s destroyed Jewish heritage, wartime crimes and culpability. I attended concerts and lectures at both the Warsaw and Krakow Jewish Festivals.

There were some rotten apples, however, in the bunch. I became the pitiful protagonist of a cliché when I had the door of my grandfather’s childhood home slammed in my face by its current resident. One morning I found “Jebac Zydow” (Fuck the Jews), a gem of anti-Semitic Polish football jargon that doesn’t actually refer to Jews, spray-painted on my apartment building. I stumbled upon mock-folk-art wooden dolls depicting Jews with money bags, for sale as good-luck souvenirs. In Sandomierz’ medieval cathedral I saw Karola de Prevot’s 1708 painting depicting the Jewish ritual murder of Christian babies, still hanging. It was especially awkward when in Warsaw, a friend-of-a-friend, after learning that I was Jewish, enthusiastically told me she lived in her grandparents’ old apartment, which had been confiscated from Jews forcibly relocated to the ghetto in 1940.

But only because I subsequently spent a lot of time in Poland is it clear to me that what’s most ridiculous about Poland’s revisionist legislation is that it does not reflect the opinion or will of a huge portion of Poles. Is there a strain of antiquated, latent insensitivity toward Jews? Yes. But the scars, questions and vacuum left by the Jewish absence in contemporary Polish life are subjects for cultural consumption. And, quite honestly, the cat of admission is already out of the bag. Polish intellectuals like Jan Tomasz Gross, Anna Bikont and Jan Blonski have already researched the facts of Polish wartime wrongdoing; young people are taking interest in Polish-Jewish heritage, and Polish presidents, like Bronislaw Komorowski and Aleksander Kwasniewski, have repeatedly apologized for Polish wartime wrongdoing.

It’s essential to mention that that my family has another indispensable story: my aunt’s mother, like thousands of Jews, was saved by a courageous Polish family during the Holocaust.

Zygmunt Miloszewski, the author of “Grain of Truth,” a novel that raises questions about Polish anti-Semitism, reflected the thinking of the younger, self-critical generation of Poles in an interview for The Times of Israel, when he said, “I have always thought that if you want to be the scion of your nation, you can only be proud of its moments of glory [once] you own up to its inglorious moments of vile behavior. The Poles like to think of themselves purely as victims and heroes…that leads straight to hatred and xenophobia.”

The sacred cow of Polish victimhood is understandable from a sociological perspective; no other country in Nazi-occupied Europe suffered like Poland. And right-wing Polish politicians are right: it was the Nazis who erected the barbed-wire fences of Auschwitz. But there was a whole country surrounding those fences, fertile with age-old institutionalized and folk anti-Semitism that allowed for a culture of schadenfreude and exploitation. There were no Germans left in Dzialoszyce when shots were fired in June 1945. Nor was it a German who, scared silly by rumors of Jewish real-estate revenge, slammed his front door on me in 2014.

But instead of nobly exploring complex parallel narratives of heroism and injustice that Poland’s millennials are already coping with, Poland’s new law rewrites history to massage the national ego and spits in the face of stories like my grandfather’s. Even worse, it cripples the pen of young Poles and Jews who are ready write their own new chapter about Poland, its complicated history, handsome blond guys and plum cake.

David Sarna Galdi is a former editor at Haaretz newspaper. He works for a nonprofit organization in Tel Aviv.