The number of classrooms, the availability of counselors and the numbers of dropout prevention programs constitute a grievous violation of the right to education for tens of thousands of Palestinian schoolchildren in Jerusalem.

By Betty Herschman

In cities around the world, most parents agonize about their kids’ first day of school. They worry about whether their kids will connect with their teachers. They worry about bullying. Mostly they anguish over the quality of education their child will receive and whether it will prepare them for a productive life beyond their school years.

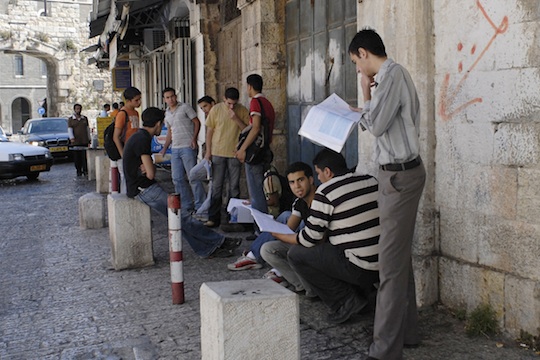

In East Jerusalem, mothers and fathers worry about whether or not their child will have a place in the classroom — indeed, whether or not the classroom will physically exist.

As the new school year begins, a gaping dearth of 2,200 classrooms endures in East Jerusalem and despite a Supreme Court ruling that the Jerusalem Municipality and Education Ministry rectify the shortage by 2016, only 150 classrooms have been built over the past five years. Furthermore, as revealed in Ir Amim’s and The Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI)’s recently released joint monitoring report on the state of education in East Jerusalem, despite an overall 13 percent dropout rate, there are no dropout prevention programs in one third of Arab secondary schools in Jerusalem.

Faced with a shortage of 2,200 missing classrooms in the official Arab school system in Jerusalem, the authorities are doing too little, too late to close this intolerable gap. Exacerbating the insult of the shameful disparities in educational resources between East and West Jerusalem is Mayor Nir Barkat’s insistence that the system is getting better. Despite Barkat’s public statements, according to which under his leadership the municipality has invested significantly more than previous administrations in improving the educational system in East Jerusalem, the pace of building new classrooms is far too leisurely to respond to the urgent needs of Palestinian children. During Barkat’s current term, from 2009 until today, only 150 new classrooms have been built in East Jerusalem, with 332 additional classrooms in various stages of planning.

As the mayor spit-shines the numbers, there is little way to dress up the dark side of this story: while the authorities maintain that a lack of suitable vacant lands in East Jerusalem is the main hurdle for the construction of new schools for Palestinian children, they are continuously advancing new building plans for Israeli settlers on the scarce available land remaining in East Jerusalem.

Also difficult to legitimize is why, despite disturbing dropout rates in East Jerusalem, the city asymmetrically focuses its dropout prevention resources in west Jerusalem. Altogether, a stunning 36 percent of children in East Jerusalem fail to complete a full 12 years of school. Despite these egregious numbers, according to figures compiled by the Jerusalem Education Administration (MANHI), in 30 percent of East Jerusalem high schools MANHI does not operate any dropout prevention program and in 44 percent it runs only one program. While 225 students in Jerusalem’s Hebrew education benefited from a national dropout prevention program in 2012, there were only 100 beneficiaries in East Jerusalem. Meanwhile, Palestinian students comprise 56 percent of the student body that MANHI oversees (the remaining 44 percent study in Jewish secular schools and Jewish national-religious schools).

It will come as no surprise, then, that there aren’t a whole lot of resources allocated to monitor the quality of education in East Jerusalem or to deal with the necessarily reduced prospects for higher education and solid career paths. There is persistent discrimination between the educational systems in West and East Jerusalem in the allotment of professional positions. Only five inspectors are employed in the East Jerusalem while in West Jerusalem there are 18 inspectors. The disparities are even greater in the case of school counselors, who play the sometimes life-saving role of providing psychological support to overwhelmed kids and preventing dropout. Only 29 school counselors operate in East Jerusalem compared to some 250 counselors in West Jerusalem, despite the harsh socioeconomic conditions that many Palestinian families face and the dire need for school staff to help kids sustain a vision of hope.

All of these inequalities — in the number of classrooms, in the availability of counselors, in the numbers of prevention programs to keep kids from freefalling through the system — constitute a grievous violation of the right to education for tens of thousands of Palestinian schoolchildren in Jerusalem. And given the persistent poverty rate in East Jerusalem — an inconceivable 82 percent for Palestinian children — failure to guarantee the universal right to a free education only adds to the dire socio-economic pressures eroding Palestinians’ grasp on the city. Such a failure demands an urgent response from officials in both the municipality and the government and from all those vying to assume leadership of the “unified, eternal capital of Jerusalem” in the upcoming mayoral elections.

Betty Herschman is director of international relations and advocacy for Ir Amim, for an Equitable and Stable Jerusalem with an Agreed Political Future.