This article was published in partnership with Local Call.

In May 1971, Israeli authorities expelled the Palestinian residents of a small village north of Jerusalem, intending to replace them with a settlement for wealthy Jewish Israelis. Then-Prime Minister Golda Meir, who approved the expulsion and the demolition of the residents’ homes, referred to the new settlement as “another Savyon,” a reference to one of Israel’s wealthiest localities, near Tel Aviv.

These revelations, discovered in materials classified as “top secret” that +972 Magazine recently unearthed in the Israel State Archives, are not merely a historical footnote. Ever since they were forced out and their homes destroyed, approximately 300 of the residents of An-Nabi Samwil — some of those who were forced out, along with their children and grandchildren — have been living in an unrecognized hamlet only 200 meters from where their old homes once stood, mostly in the houses of other Palestinians who fled the village during the 1967 war.

The building plan for the new Jewish settlement in An-Nabi Samwil went through various iterations, and was eventually discarded in the mid-1980s due to opposition on environmental and technical grounds. But the evicted Palestinian residents remain forbidden from returning to their demolished homes, and the area has since been declared a national park and an archaeological site.

Those Palestinians who still live in the area are denied sewage and road infrastructure as well as building permits, and have been cut off from the rest of the occupied West Bank by Israel’s separation wall. At the same time, they are not allowed to enter nearby Jerusalem — a one minute drive away — without a permit, which most residents do not receive.

Over the past month, the Palestinians of An-Nabi Samwil have been holding weekly demonstrations demanding that Israel recognize the village in its current location and allow them to build there, as well as grant them permits to enter Jerusalem and ease the restrictions at the nearby checkpoint when they cross into the West Bank.

According to Jewish, Christian, and Islamic tradition, An-Nabi Samwil is the site of the tomb of the Prophet Samuel. Many Jewish believers come to pray at what is believed to be the tomb, located in a cave of a Crusader-era structure, which was once part of the village. There are also antiquities at the site, as well as signs that narrate a history from the First Temple to the Six-Day War, with no mention of the village that was uprooted or its residents who live nearby.

‘Is this life?’

Nour Barakat is a mother of four. Dressed elegantly with a bag draped over her shoulder, she told me that it took her three days to clean the sewage and dirt that flooded the home in which her children live. “We live in four different homes that share the same sewage pit. And it is small. Our neighbors use the bathroom and everything floods from our kitchen sink. The smell doesn’t disappear for days.”

None of this is Barakat’s fault. The residents of An-Nabi Samwil are forbidden from using normal sewage infrastructure, and the army did not draw up a new statutory plan for the village after the residents were expelled. This means people are forced to throw their garbage out into the pits in the yard or pour it into the valley at the edge of the village.

Barakat described how a year ago, an Israeli police officer who was patrolling in the village pointed to the low-ceilinged room where her four children sleep, and asked another officer if those were horse stables. She said that moment broke her. “I cannot live like this. The houses here are completely destroyed and we are not allowed to renovate them or build — because the army will destroy them soon after.”

In another house were five children living bed-to-bed in a small rectangular room. One family lives in a peeling white trailer; another lives in a cave. Some of the residents live in the same stone houses to which the army moved them in 1971, as Israel forbids building new rooms or homes here.

As elsewhere in Area C of the West Bank, which is under complete Israeli civil and military control, this is a form of slow expulsion, aiming to displace a cohesive community with the intention of using their land for the interests of Jewish Israelis. And indeed, most young Palestinians in the community simply leave.

Aida Barakat, an elderly woman, sat on a thin mattress, cutting open pods of okra. Her home consists of one room, where the toilet, the sink, and the bed sit alongside one another in the same space. She and her grandson sleep there. “Is this life?” she asked me. “I’m sleeping in the kitchen.”

The head of the local council, Amir Barakat, greeted me with considerable reluctance. “It’s as if we don’t exist in your eyes,” he said, showing me a structure he had built for his children. I asked him what the difference is between a tin home and a regular house. “The humiliation,” he replied.

Eid Barakat, a local activist, told me that he left the village, but returned to it after his parents died. Only then did a place become available for him. “For 20 years we have been trying to submit a statutory plan to the Civil Administration,” he said, referring to the branch of the Israeli army that is charged with running the day-to-day life of millions of Palestinians under occupation. “They don’t let us.”

“Every few years, a new officer in the Civil Administration comes, makes promises, and in the end nothing is done,” Eid continued, as his grandson, who is named after him, played soccer with a group of girls on the driveway near us. “All our homes have demolition orders. I dug a well; they destroyed it. I built a fence; they destroyed it. I planted trees; they were uprooted.”

‘They pulled us out of our homes by force’

In 1995, then-Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s government decided to declare 3,500 dunams around An-Nabi Samwil a national park — just before the Oslo Accords came into effect, which would have prevented Israel from making further such declarations. The Civil Administration currently mentions the national park as the reason for banning construction in the village, claiming that doing so is necessary to preserve the local ecology.

The national park not only includes the center of the historic village, from which the residents were expelled in 1971, and where the prophet’s tomb is located, but also the new location to which the residents were forcibly relocated — a fairly arid plain where no unique ecology is evident.

Eid Barakat and I walked through the village together. In the yard of one of the homes we saw a fence made out of red barrels; if it were a real fence, he said, it would be considered illegal construction and the army would demolish it.

He pointed to a large field: “I made it for the children with synthetic grass,” he said. “But the army told me grass was not allowed. So I removed the grass. Then they told me, ‘You made a four-meter fence, and we only allow a two-meter fence.’ I asked why, and there was no answer. So I lowered the fence.”

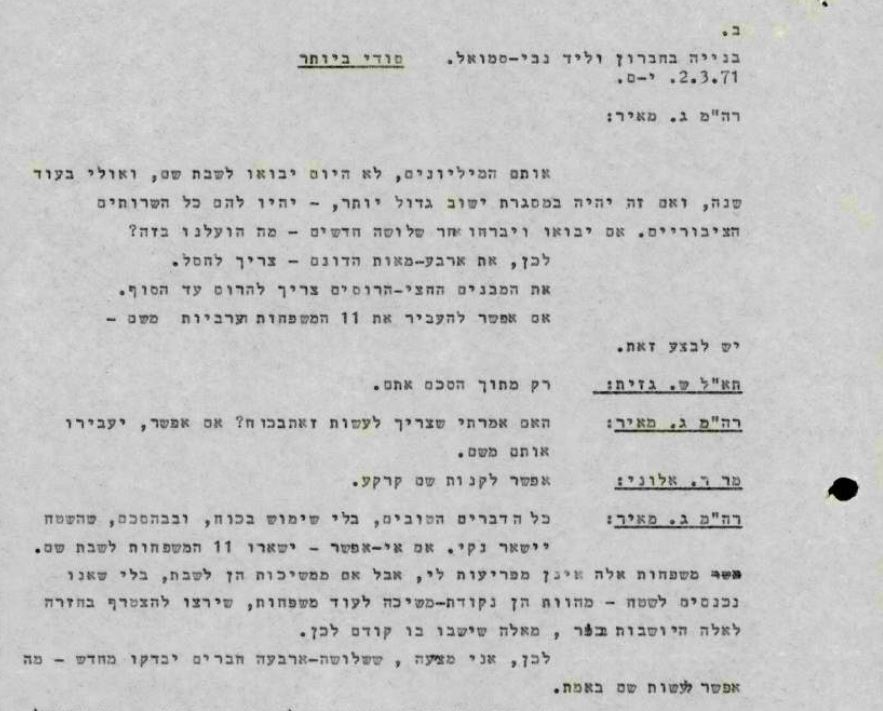

The answer to Eid’s question may be found in those dozens of archival documents. During a 1971 meeting, the Israeli government made several decisions that would ultimately lead to the expulsion of the residents and the demolition of their homes two months later.

“If it is possible to move the 11 Arab families from there — it should be done,” then-Prime Minister Meir told a room full of a small number of top government officials, during a discussion on how to establish a new settlement for Jews at a site populated by Palestinian families. “These families do not bother me,” she said, “but if they remain there without us entering the area — [they] will attract more families who will want to return and join them, from those who used to live there.”

The families likely to return to the village were the 700 residents of An-Nabi Samwil who fled their homes during the Six-Day War and were not allowed to return. From a village of more than 1,000 people, only 300 remained after 1967.

When Meir proposed expelling the remaining residents of the village, Shlomo Gazit, head of the Military Government Department, commented that this would be possible “only through agreement with them.” Meir asked, “Did I say using force?”

Cutting off the conversation, she said: “All the good things [hinting at the usual methods for displacing Palestinians], without the use of force,” adding: “May the area remain clean.”

The minutes from that meeting listed three objectives: to destroy the village’s empty buildings, to buy the residents’ land, and to “conduct negotiations with them” so that they would move elsewhere. In practice, this is not what happened.

“It happened at four or five in the morning,” recalled Eid, who was eight years old when the expulsion took place. “At first the army came. They closed the village. Then, the bulldozers and the trucks. They pulled us out of our homes by force.”

“We had beautiful houses, each with two floors,” said Aisha Barakat. “There were residents who removed everything from their homes, but my father refused. We left everything inside. Even ID cards. They tied iron chains to our houses and pulled until the buildings collapsed. It took them a long time.

“We lost everything like that,” she continued. “The houses we live in today are not ours; the army transferred us to them.” Soldiers concentrated the residents in the current location of the village, in several stone houses which belonged to Palestinian “absentees” — Israel’s term for those who fled or were expelled to “enemy countries” in 1967. All the rest of the buildings were destroyed. Eid said that the soldiers offered the residents financial compensation, but no one agreed to take it.

When I told people in the village about the documents I found in the archives, which testify that the purpose behind the expulsion was to establish a Jewish settlement of luxury villas, they said it was the first time that they had heard about it. “The soldiers told us it was because our houses were old and they were worried about us,” said Eid.

“Our house was on the second floor,” he continued. “I remember they threw all our belongings from the top, and they threw our wardrobe off the balcony. There was a dog, belonging to one of our neighbors, that wouldn’t leave the house. The walls were demolished on top of it.”

Mission accomplished

A few days after the residents were expelled, Minister Yisrael Galili wrote to Meir that the mission had been completed successfully. “The area next to the mosque was leveled,” the buildings were destroyed, and the deportees “received compensation.”

He then informed her that a Jewish settlement could now be built at the site. “According to the assessment of the Israel Land Administration, the vacated area has space for 1,000 lots,” wrote Galili. He referenced a government decision from 1970 that the settlement “will be a residential area for people of means, so that the state’s participation in the expenses will be minimal.”

“I saw before my eyes another Savyon blooming and rising,” said Meir in a meeting regarding the planned Jewish settlement in 1971; although uncomfortable that it would exclude less affluent Jews, Meir understood the logic behind a settlement that wouldn’t require major government expenditure.

An-Nabi Samwil is located atop a mountain, with breathtaking views. Galili claimed that for this reason it would be easier to find tenants to live there, and also people who would build houses with their own money. “It’s a beautiful place, and there is nowhere like this in Tel Aviv,” said Meir.

Documents in the archive reveal that only three months after the expulsion of the Palestinians, 633 Israelis requested to purchase a plot of land in the area and settle the depopulated mountain. “Civil servants, families of soldiers, teachers, lecturers, and others from the university, and other citizens,” read the list of the Defense Ministry’s Commissioner of Government Property and Abandoned Lands in Judea and Samaria in August 1971. Even Habima, Israel’s national theater, requested a plot.

A year after the expulsion, in June 1972, the Israel Land Administration sent Golda Meir a plan for the settlement of An-Nabi Samwil, which included 1,400 lots, public buildings, shopping centers, and roads. The document states that of the 2,154 dunams that are the village’s land, 1,076 dunams are owned by Arabs — some of them “absentee Arabs who are residing in enemy countries,” and the rest belonging to “nine Arab families living in the village.”

Unlike many areas around Jerusalem, Israel did not annex An-Nabi Samwil immediately after the 1967 war, and the border of Israel’s expanded Jerusalem runs just one kilometer south of it. This is how the situation remains to this day: the village, which is between the settlements of Ramot and Givat Ze’ev, is located in Area C. This state of affairs contributed to the expulsion decision.

“It was a grave error not to include the area of An-Nabi Samwil in the territory to which Israeli law was applied,” wrote Galili to Meir in 1973. “The political circumstances can change, and it is likely that our strength there will be threatened. It is a necessity that Jews live there.”

This was a theme repeated by government ministers throughout those years, as recorded in the archives, going back to Yigal Allon in 1969. In a meeting about An-Nabi Samwil in 1971, Meir herself stated: “We need to ensure that this does not become an area that is beyond Israel’s borders again. The question is how to ensure this.”

Their words explain the logic that led to the expulsion of the Palestinians. In the years immediately following the 1967 war, the possibility that the occupied territories would be returned seemed more realistic, and the establishment of a Jewish settlement was an attempt to guarantee that An-Nabi Samwil would remain under Israeli sovereignty.

From this perspective, holding onto the village was important for various reasons. Firstly, its location is strategic, being one of the highest peaks in the region, dominating its surroundings and overlooking Jerusalem. Secondly, it has religious significance, with the village traditionally being identified as the location of the prophet Samuel’s tomb. It is also, perhaps, emotionally significant: in the 1948 war, the Haganah failed in its attempt to capture the village in Operation Yevusi, and several dozen soldiers were killed. Previous attempts by Jews to settle there also came to nothing.

But the Jewish settlement in An-Nabi Samwil was never built, for two reasons. Firstly, Israelis strongly opposed construction on the mountain, afraid it would spoil the landscape. “Construction on the ridge will be visible from afar and in our opinion will damage the entire environment,” the Council for a Beautiful Israel wrote to Meir in 1972.

Then-Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek also expressed strong opposition to the settlement of the mountain, which he envisioned as part of a “green ring that will surround Jerusalem.” Galili, who was in favor of the construction, wrote in response to Kollek: “With all due respect to ecological considerations, these are not considerations [that should affect] critical national considerations.”

Secondly, the area was, unsurprisingly, discovered to be privately-owned Palestinian land. In a 1973 meeting, then-Attorney General Meir Shamgar told members of the government that the state could not expropriate the land if its owners were present. Those present owners were, of course, the same 300 residents of An-Nabi Samwil who were deported in 1971.

Yet Shamgar added an important caveat: that it would “be possible to compel the present owners not to do construction work,” an idea that was repeated in different ways across the archival documents. Even if the government could not establish a Jewish settlement on the mountain, the thinking went, it must at least prevent the Arabs from building in An-Nabi Samwil. Then-Health Minister Haim Gvati, in a 1971 meeting, even termed such an intervention as “preventive.”

In this sense, the Rabin government’s 1995 declaration of a national park in the area continued the process started by the Meir government, preventing — to this day — An-Nabi Samwil’s residents from building on their own land.

A version of this article first appeared in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.