On Feb. 21, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear Arkansas Times LP v. Waldrip, a case challenging a law targeting forms of boycotts, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) against Israel. The Arkansas Times, a local newspaper based in Little Rock, had little if anything to do with Israel; but in 2018, it discovered that in order to renew a contract with the state government to publish advertisements on its pages, the newspaper had to sign a form declaring they are not and will not boycott Israel, in accordance with a law passed by the Arkansas state legislature a year earlier. Though not actively engaged in such a boycott, the Times refused to sign the form, arguing that the state could not compel the newspaper to take a position on the political issue.

The question at the heart of the case was whether political boycotts — a nonviolent tool used throughout U.S. and global history — are a protected right. In a unanimous ruling from 1982, NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware, the Supreme Court declared that boycotts were a form of political assembly and expression and therefore a protected right under the First Amendment. In the last decade, however, a majority of states have passed legislation banning boycotts directed at Israel, seemingly in violation of the judicial precedent.

Represented by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the Arkansas Times sued the state government on the grounds that the 1982 ruling prohibited the BDS ban. However, the Eighth Circuit Court, which covers Arkansas and much of the upper Midwest, ruled against the newspaper and upheld the anti-BDS law. The ACLU appealed the case to the Supreme Court, but their petition was denied a hearing.

In a conversation with +972, Brian Hauss, the ACLU lawyer representing the Arkansas Times, explained that while the court’s decision does not mean the laws are explicitly upheld, it does give states more time and flexibility to expand the existing legislation in “draconian” directions, including by criminalizing boycotts and making them punishable by law. “We’re at the top of a slippery slope,” he warned.

Nonetheless, Hauss emphasized that such civil rights struggles are “always long-haul propositions,” and further stressed that “as long as people continuously advocate and exercise their rights, it’s very hard for the government to truly suppress them.”

Hauss has also appeared in “Boycott,” a documentary focused on this case and others on the issue, produced by Just Vision, with which +972 is affiliated. The film is available for streaming starting March 1.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

First of all, how are you doing, and how is the staff at Arkansas Times doing? What’s the sentiment among the group?

Obviously we’re disappointed. Of course, I’m biased, but I think we presented a compelling case for why the Supreme Court needs to take up this case. What we have is a pretty clear conflict between the Eighth Circuit’s decision and the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision from 40 years ago, which said that the power of the states to regulate economic activity could not justify the suppression of a boycott. I don’t know how you reconcile those two holdings, and we were hoping the Supreme Court would step in and clarify that the Eighth Circuit got it wrong here.

Its decision to continue sitting this out for now basically means that there’s going to be more confusion in the lower courts, and legislators who want to adopt anti-boycott legislation are going to feel emboldened. This means we’re going to have to continue the fight outside the rarefied arena of the Supreme Court and instead be in the messier place of state courts, federal courts, and state legislatures around the country.

For people who don’t know so much about the case or maybe just heard about it last week, could you run through the basics of the case? Feel free to get into as much of the legal weeds as you want.

You’re going to get more than you bargained for!

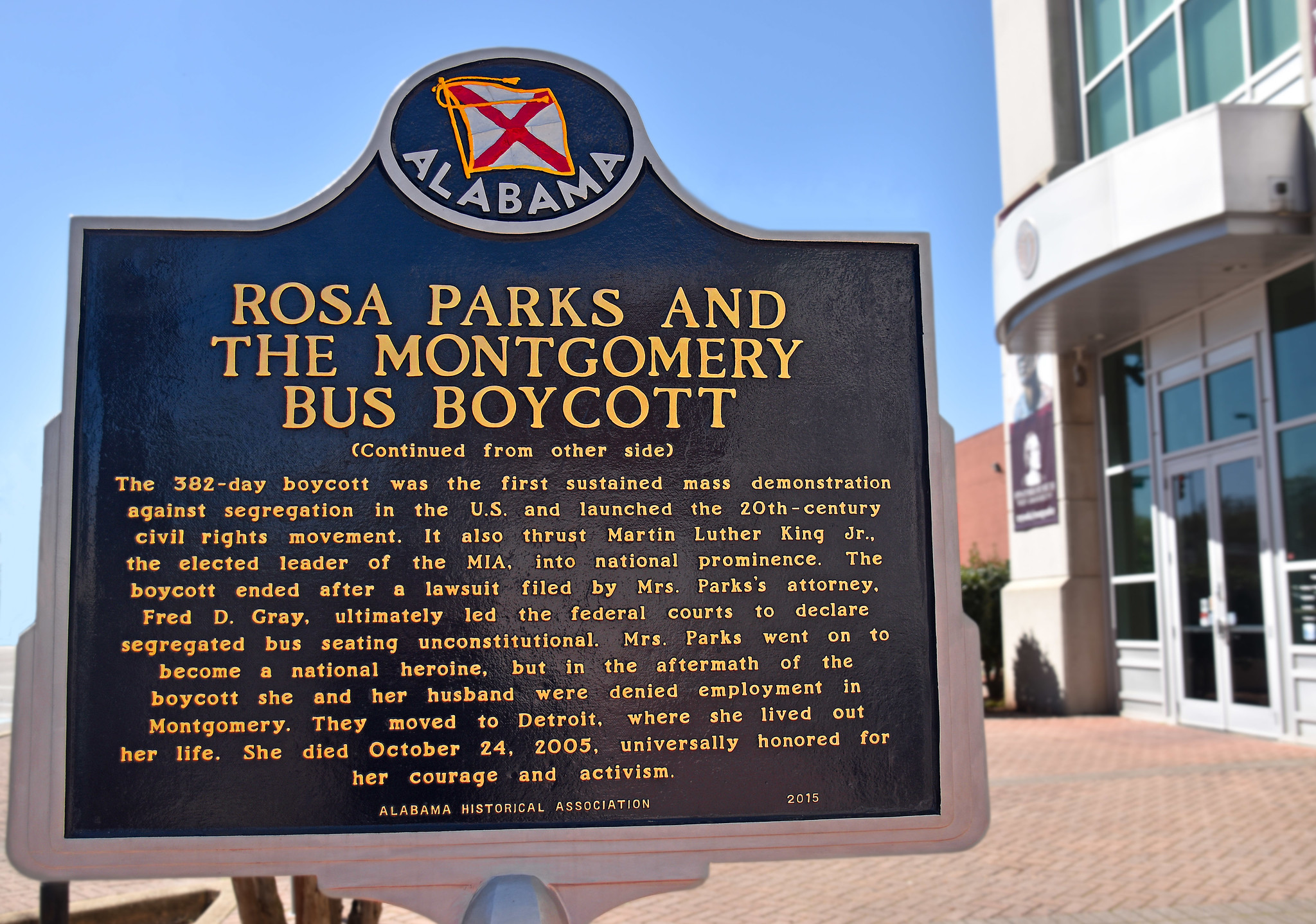

First of all, boycotts were an essential tool in the civil rights movement. During that time, the Black residents of Port Gibson, Mississippi collectively decided to boycott white-owned businesses to protest ongoing racial segregation and inequality in their community. The businesses sued all of the boycott participants for all of the losses resulting from the boycott.

The lawsuits went all the way to the Supreme Court, and the court had to decide whether the boycott was a constitutionally protected assembly, or whether it was an unlawful conspiracy. And in NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware, the court basically said that the Black citizens of Port Gibson had banded together to express their outrage against the social system that had consistently treated them as second-class citizens. It said that this practice is deeply embedded in American politics, that it was constitutional.

For four decades after Claiborne Hardware, you saw almost no government attempts to directly suppress peaceful consumer boycotts. Then around 2015, things started to change. That’s when we see the first anti-BDS law passed, and virtually all of these laws look the same [since 2015, 35 states have passed anti-BDS legislation]. Eugene Kontorovich [a law professor affiliated with the right-wing Kohelet Policy Forum] has admitted that he is the author of most of these laws and that he’s crafted model legislation that various states have implemented.

Most anti-BDS laws require government contractors to certify that they’re not participating in boycotts of Israel or territories controlled by Israel, which really means Israeli settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories. And if the contractor refuses to make that certification in most states, they can’t get a government contract.

As soon as these anti-BDS laws started getting passed in state legislatures, the ACLU started pushing back against them. We filed an amicus brief in the original Claiborne Hardware decision 40 years ago — the right to boycott has always been something we’ve been interested in supporting. Our line was that they violate the right to boycott, and that whatever you think about BDS, the government has no business regulating it.

We had a few early victories, but the big case was with the Arkansas Times. It’s a local news magazine that previously contracted with the state for advertising, and in order to renew those advertising contracts after the state passed the anti-BDS law, the Arkansas Times was forced to sign this anti-boycott certification. And they refused to sign it.

The Arkansas Times is not boycotting Israel. They really don’t have a particular stake in that fight – they’re a local newspaper that covers Arkansas politics. But as journalists, they regard the First Amendment as sacrosanct, and they weren’t prepared to sign a form disavowing their freedoms in order to get these advertising contracts. Alan Leverett, the newspaper’s CEO, said “if we did that, we wouldn’t be worthy of the First Amendment protections we enjoy as journalists.” They viewed themselves as necessary defenders of these freedoms.

The Eighth Circuit Court agreed to hear the case, but ruled that the anti-BDS laws could stand.

You can’t ignore that there’s been a tradition in this country for 250 years of people engaging in consumer boycotts to express their political beliefs, going back all the way to the Boston Tea Party. And I think most people today, Americans of every political stripe, are probably boycotting something or other. They intuitively understand that it’s a form of political expression. Even [Republican] Senator Ted Cruz, who’s a big supporter of these anti-boycott laws, didn’t like that Nike, in his opinion, had “gone woke” with its Colin Kaepernick ads, so he tweeted something like, “I respect free speech and I’m exercising mine. I will no longer purchase Nike products.” People get this intuitively; they just don’t get it when it comes to boycotts of Israel.

For people following the case, it was surprising to hear that the Court decided not to grant certiorari [agreement to hear the case]. Why do you think they chose not to hear it?

A caveat to all this is that this is pure speculation; I have no insider or special knowledge here.

It’s important to understand first that the Supreme Court almost never grants cert petitions, so every petition is kind of a longshot, “Hail Mary” situation. The most likely situation in which it’s going to grant a petition is either when an act of Congress has been struck down by a lower court, or when you have two circuit courts in disagreement with each other. In those situations, the law with respect to federal statute or the federal constitution in one part of the United States is different than the law in another part. And when you have those conflicts, the Supreme Court says, “okay, now there’s a problem because judges around the country don’t know what to do.”

We have this unanimous Supreme Court decision from 40 years ago and very robust agreement about how that decision works. And only very recently, states have been passing these anti-boycott laws. So right now, all we have on the books is the Eighth Circuit decision. Often the Supreme Court says, “we’d rather wait and see if all the courts line up on one side of the issue, or if they don’t, then the conflict will be presented more sharply, and we’ll have all the arguments fully aired out and can resolve it then.” We tried to say that they don’t need to wait because they actually decided this issue already.

So I wouldn’t necessarily read it as the court expressing its views on the merits. I read it more as them saying “we don’t need to go there yet, we can let this play out a little bit longer.”

Could you clarify where the legal status of the right to boycott stands now? There was some hasty reporting that said the Supreme Court “upholds” the Arkansas law.

The most important thing is that the Supreme Court’s denial of cert is not precedential, and it expresses nothing about the court’s consideration of the merits. It simply means that the lower court’s decision stands. So in states that are subject to the Eighth Circuit, the Arkansas Times decision means the individual acts of economic activity, or individual refusals to deal as part of a boycott, are not protected by the First Amendment, and many of the anti-BDS laws will likely be held constitutional in that jurisdiction.

For all the other circuit courts, the Eighth Circuit decision does not bind. Others can look to it as persuasive authority, but it’s only as persuasive as they find it. We would argue that Claiborne Hardware is still binding authority on those other jurisdictions, and if those courts agree with us, they’re bound to apply that law. That’s going to have to get fought out in each circuit.

Part of what was really interesting about this case is that this extends far beyond BDS and the issue of Israel-Palestine. There have recently been a series of new laws banning all sorts of boycotts. Could you talk about how this decision will impact other issues?

These new laws are really copycats of the anti-BDS laws, almost identical in most respects. Starting a year or two ago, Texas and Kentucky adopted legislation that is basically a copycat of the anti-boycott laws but for firearms manufacturers and fossil fuel companies.

This legislative session, the Heritage Foundation and the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) initially drafted model legislation called the “Eliminate Political Boycotts Act,” which is pretty transparent about what it is trying to do. I think they realized that was bad messaging, and so they pretty quickly changed the name to the “Eliminate Economic Boycotts Act” which seems more forgivable somehow.

It covers a laundry list of conservative hobby horses: it would limit boycotts of fossil fuel companies, firearms manufacturers, mining companies, timber interests, companies that don’t meet workplace diversity criteria, companies that don’t meet environmental responsibility criteria, companies that aren’t transparent about their workplace diversity or environmental sustainability practices, companies that don’t provide reproductive health care, or companies that don’t provide gender-affirming care.

Although so far this has really been mostly a conservative hobby horse, I think it’s only a matter of time before you start seeing [predominantly Democrat-voting] blue states lining up behind their own version of anti-boycott legislation, like state contractors forced to certify that they won’t boycott companies that support Planned Parenthood, or something like that. I think you’re going to start seeing an arms race in this.

The mechanism by which states are ensuring that you are not boycotting Israel is mostly by controlling the activity of state contractors. Most people aren’t state contractors, so these laws don’t apply to them. But is there any chance that these laws will get more stringent and pervasive? Could the mechanism change such that declaring something like “I am choosing not to eat Sabra hummus and I urge all of you not to eat it as well” could be outlawed?

As I read the Eighth Circuit’s ruling, there’s nothing that prevents the state from enacting more draconian legislation, even though the ruling is not definitive on that point. The ruling can basically be boiled down to: the act of boycotting is not protected by the First Amendment. Nothing about that suggests it applies only to government contracts. If the act of boycott is not protected, then it’s hard to understand why the government couldn’t impose civil liability on you for doing it, or even make boycotting a crime.

That’s not completely hypothetical: in previous Congresses, we’ve seen the Israel Anti-Boycott Act get introduced. That legislation would have made it a crime, even a federal felony, to participate in boycotts of Israel called for by international governmental organizations like the UN Human Rights Council. So if that bill had passed — and thankfully it didn’t — if you went on Facebook and said, “I support the UN Human Rights Council’s call for a boycott of businesses operating in Israeli settlements in the West Bank,” the act would make that a felony. We’re at the top of a slippery slope here.

So far, anti-boycott laws have been relatively narrow. I think a lot of it is designed to be a talking point, so that the state can say we’ve outlawed boycotts of Israel without really getting its hands too dirty. But we’re starting to move down a little further. The Eliminate Economic Boycotts Act that’s being proposed gives the Attorney General pretty sweeping powers to investigate companies that are perceived to be violating the act: it has subpoena power, it can interview witnesses, it can force the companies to turn over their business records. So we might start seeing intense government investigations into private companies.

How is the state going to know that you’re not boycotting Israel? They’re going to look at your speech; if you have a bunch of social media posts that are very critical of Israel, or if you’re part of an organization that’s critical of Israel or the settlements, the state might say, “That’s decent evidence that you might be boycotting because a lot of the people in that group are boycotting, so maybe you’re doing it too. We need to see all your business records, please hand them over.”

Realistically, we will be looking at a new version of the Red Scare [a fearful hysteria against communism and leftist ideologies during the early-to-mid 20th century]. If the states decide to start robustly enforcing this, individuals or companies that speak out on these issues are going to have to worry that a representative from the state will be combing through their private messages and receipts to look for evidence of unlawful boycott activity. It’s kind of like if you give a mouse a cookie: the more you allow this stuff to go on, the more it’s going to build inertia, and the more aggressive the anti-boycott proponents are going to be.

What advice would you give to activists or people who are currently engaged in either BDS or other realms of boycott that will soon be targeted by this legislation? And what are the next legal steps?

The advice question is always hard. I suppose the best advice I can give is: don’t lose hope. So far at least, the legal restrictions are relatively narrow. Even in the Eighth Circuit, most people who are not government contractors have every right to go ahead and continue boycotting to their heart’s content. And I would say to government contractors outside the Eighth Circuit, if you’re being asked to sign these forms, please call your local ACLU affiliate, because we might be interested in talking to you.

More generally, these big fights over civil liberties issues are always long-haul propositions. I wish victory had come in a single ruling in this case, but that’s usually not how it goes. It usually takes many, many years of continued struggle. The downside is that it can be exhausting, but the upside is that as long as people continuously advocate and exercise their rights, it’s very hard for the government to truly suppress them. You shouldn’t let discouragement prevent you from continuing to engage in dissent. The whole point of dissent is that you’re often up against steep odds, and it’s by persisting in the face of adversity that change comes.

In terms of next legal steps: the Council on American Islamic Relations (CAIR) has cases in the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits, so we’ll see what those courts do. But to get more legal clarity on this, I think we just have to keep bringing cases and making our points as forcefully as we can, and trying to build up the consensus on this.

Part of what’s been difficult about this is that if you don’t exercise muscles, they atrophy. We haven’t had to have a big First Amendment fight about the right to boycott for a long time — not since Claiborne Hardware was decided. When you have those absences, room opens for these debates that should be foreclosed. The more persuasive cases we can bring, with people who are engaged in what everybody would acknowledge to be a fundamental form of political protest, I think the better odds we’ll have of eventually convincing the Supreme Court that this is just not an area where the government should be sticking its nose in.