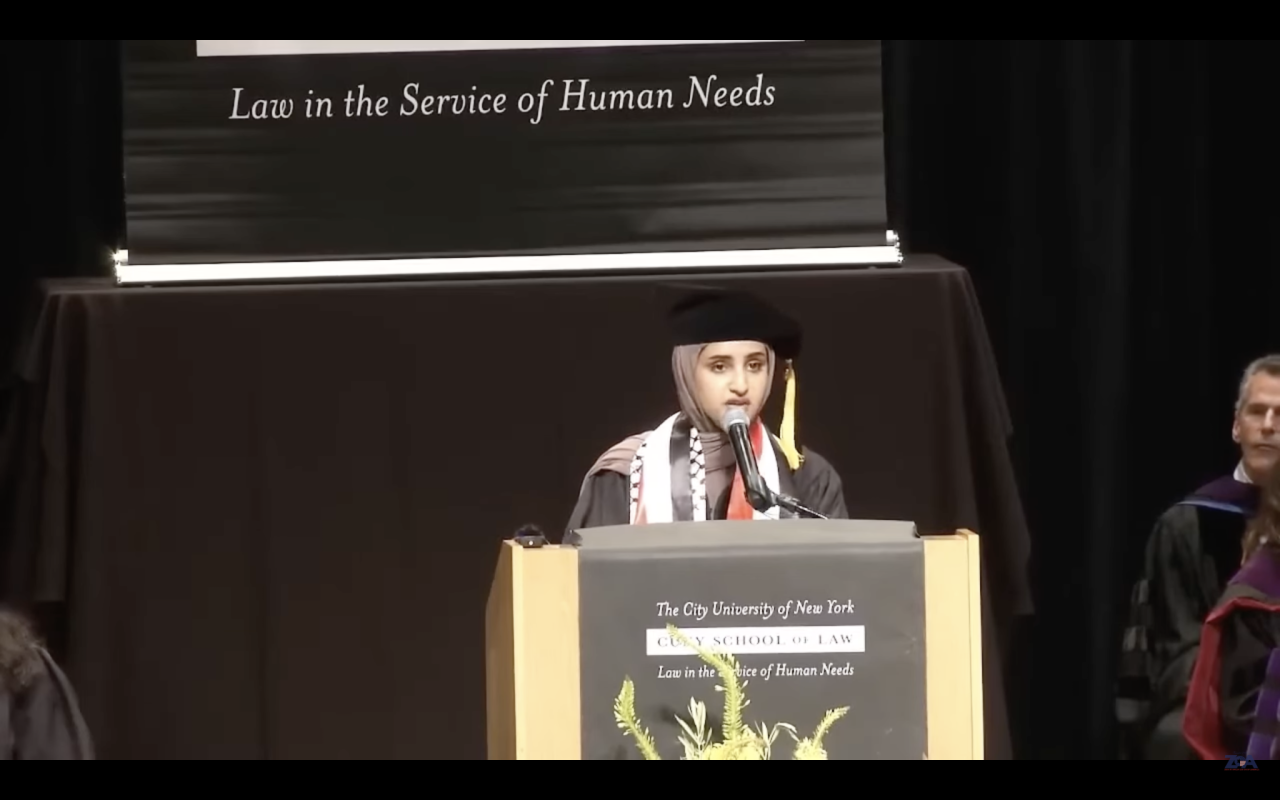

Fatima Mohammed, a graduating law student at City University of New York, came under a firestorm last month after delivering a commencement speech that — in addition to criticizing U.S. police brutality and immigration forces — hailed her peers for standing up for Palestinian rights and calling out Israel for its oppressive regime. Across op-ed pages, social media, City Hall, and Capitol Hill, the Yemeni-American graduate was accused of “Jew hatred” warranting immediate punishment of her and of CUNY itself for enabling such purported antisemitism.

The vehement opposition to Mohammed’s speech is merely the most recent example in what is emerging as a depressingly familiar pattern. For years, the American-Jewish establishment, conservative and some mainstream media, and right-wing Jewish pressure groups have insisted that U.S. universities are experiencing an unprecedented level of antisemitism. This is, so the narrative goes, a dangerous time to be Jewish on campus, and the threat is coming from students, faculty, administrators, and university leadership.

Much of this “wave of antisemitism” argument is driven by these groups’ ever-intensifying push to frame anti-Zionism, and most criticism of Israel, as antisemitism — a tactic that effectively delegitimizes the Palestinian liberation movement, and which disproportionately targets Palestinians themselves. Yet the picture is complicated by the fact that the past several years have seen a broader surge in antisemitism at every level of society, from the corners of the dark web to political rallies to the White House.

Amid these crosscurrents, piecing together what is actually going on at U.S. higher education institutions — and what is not — has been extraordinarily difficult, especially when many mainstream media outlets are “start[ing] from the premise that antisemitism is surging on college campuses and work[ing] back from there,” according to Arno Rosenfeld, who has been reporting on college campuses for The Forward for the past several years. What’s more, he says, this narrative is largely contradicted by data gathered by the very organizations decrying the antisemitism crisis on campus, raising broader questions about who exactly the narrative benefits — and who it harms.

I spoke with Rosenfeld about how this narrative came about, what he’s learned from reporting on it, and what, based on his experiences, is really happening around antisemitism in U.S. higher education.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Let’s start out with the big question. Is there, as we’re constantly hearing in the media and from the American-Jewish establishment, a wave of antisemitism sweeping American college campuses?

It’s a hard question to answer, for a variety of reasons. The first is that there’s not much good historic data on what antisemitism looked like on college campuses. And the second is that it depends on what you consider a “wave,” or what your threshold is for considering antisemitism to be a big problem.

What we do know from the data that exists — and this data is largely generated by the same organizations claiming there’s a massive antisemitism problem — is that the majority of Jewish students say they haven’t experienced any antisemitism over the past year, and around 85 percent have never felt excluded from a campus space because of their Judaism or any need to hide their identity. Some report zero problems, some report maybe one antisemitic experience. But the vast majority of Jewish college students report that antisemitism is not hindering their college experience. It’s not part of their daily life on campus.

But then we have 10 to 20 percent that do report a severe problem with what they consider to be antisemitism: [they report] being excluded from spaces on campus because of their Jewish identity, having repeated antisemitic comments made to them, and so on. Different people will look at those numbers and draw different conclusions. But the fact that, for example, 94 percent of Jewish college students told Hillel [International] and the ADL [Anti-Defamation League] in a 2021 survey that they had never been excluded from a group or event because they were Jewish — those numbers don’t really match the rhetoric that we’re hearing from a lot of these national organizations about the supposed threat of antisemitism on campus.

Where is this narrative of an all-encompassing wave of antisemitism coming from, if the numbers don’t really back it up?

One of the things that’s going on is that no one really wants to dispute that antisemitism is a problem on college campuses or anywhere else. There are some exceptions, but everyone in polite political discourse thinks antisemitism is bad, just like racism and other forms of discrimination. So when these sometimes false or misleading narratives get put out there, there’s no real incentive for anyone to object to them.

The other thing we know is that Jewish students who are part of Jewish communities on campus — so the most engaged Jewish students — report, at least in the little bit of data we have, higher levels of antisemitism. One thing we often see thrown around is that more than half of Jewish students report antisemitism being a problem. That’s not true, but that number — which has been reported on a lot — comes from a survey of Jewish fraternity and sorority members. Something like 65 percent of members of AEPi, the main Jewish fraternity, have reported feeling unsafe because of antisemitism on campus.

There are lots of people who do other Jewish activities on campus, but it suggests that people who are engaged in institutional Jewish life on campus may experience antisemitism at a higher level. And if you’re a national Jewish organization, that’s who you’re hearing from. That can either lead to a distorted picture, or it’s evidence that antisemitism is a bigger problem, but it’s only being visited on people who are known to be Jewish on campus.

Who — or what — is served by this narrative of Jewish students being under unprecedented siege on college campuses?

It serves organizations that are holding themselves out as protecting Jewish students. That’s not necessarily political, but it serves people who want to police speech around Israel on college campuses. To the extent that antisemitism is showing up in activism around Israel, [these organizations] would say that that speech does need to be policed — so in many cases [that belief] is not even hidden.

But there’s no understanding of the connection between, say, the way we talk about mezuzahs being ripped off door frames at the University of Indiana, and the idea that we should ban certain speakers critical of Israel from appearing on campuses. And there is a connection, because you start with the premise that things are really dangerous for Jewish students, and then you propose a bunch of solutions that often deal a lot with Israel and don’t speak to the specific needs of Jewish students.

Let’s dig down into the primary tool used by a lot of these national Jewish organizations to classify conduct as antisemitic: the IHRA working definition of antisemitism. It’s brought speech and activism around Israel-Palestine to the heart of the national conversation on antisemitism. Can you talk about how this definition came to play such an important role in the campus antisemitism debate?

What I just explained is the “good faith” narrative: there are a lot of people who genuinely care about Jewish safety, and that’s how this narrative [of a wave of campus antisemitism] can develop, even among people who have no other political agenda.

But there is also — and this is related to the IHRA definition — a concerted political effort to classify certain kinds of anti-Israel activism on campus as antisemitic. In order to facilitate that, it’s helpful if antisemitism is viewed as a really serious issue on college campuses — because if people think it’s irrelevant, why would they risk wading into adjudicating when Israel activism crosses a line [into antisemitism]? But if it’s viewed as a crisis in which Jewish college students are unsafe and something needs to be done to protect them, then it’s much easier to come in with a solution that also has a political agenda or motive around Israel.

The IHRA definition plays a funny role in these campus debates. In the U.S. context, there have been very few cases where something has been deemed antisemitic solely because of the IHRA definition. It’s really more symbolic in the sense that people promoting it on campuses typically believe that anti-Zionism is generally antisemitism, and they want institutions to adopt that understanding.

It’s messy, because while they’re asking universities to adopt [the IHRA definition], they insist they’re not trying to crack down on expression or speech around Israel. But if you tell a university, “adopt this definition of antisemitism, but don’t worry, it doesn’t have anything to do with Israel speech,” and then two years later you come and say, “based on this definition you adopted, we think you need to ban Israel Apartheid Week” — it remains to be seen whether those universities are going to agree or not.

[The IHRA definition] is viewed as this really menacing thing by a lot of pro-Palestinian activists, but I don’t know that we’ve seen it actually implemented by universities in a particularly aggressive way. With the universities that have been willing to adopt it, you can almost draw a parallel with putting out a statement saying that Black lives matter during the George Floyd protests — it’s a really easy thing for a university to do.

It’s hard to stop antisemitism and racism, so when organizations come to a university that has had a genuine problem with antisemitism — swastika graffiti or assaults — and the Jewish community is saying, “just adopt this definition,” it’s very appealing. It’s something concrete they can do, and they’ll get a lot of praise from establishment Jewish organizations, but they don’t have to put more funding toward anything, they don’t have to change their other policies or start trainings.

But this goes beyond the institutional adoption of IHRA. There are also the wider ripple effects that Palestinians and Palestine solidarity activists report in terms of the general atmosphere it creates on campus — and their sense that it’s playing a role in what they feel they can or can’t say, leading people to silence themselves. What proactive steps are the pro-Israel crowd taking to try and encourage that atmosphere?

I’m a little skeptical of the power of the IHRA definition alone, just because I haven’t seen many cases where people who might not have otherwise considered anti-Zionism to be a form of antisemitism look at the IHRA definition and suddenly change their minds. However, the push for the IHRA definition is evidence of, and goes hand-in-hand with, an increase in the effort to classify that type of speech or activism as antisemitic. That can definitely have an impact on people’s comfort levels in speaking out on these issues.

At the same time, we’re seeing a significant increase in pro-Palestinian activism on college campuses. Academics and student groups are saying things we would not have seen just a few years ago. One example is the Harvard Crimson endorsing BDS; people are obsessed with Harvard and a lot was made of it, but it’s still a genuinely significant shift. So that makes it really hard to measure any sort of chilling effect, because if there was no attempt to classify some of that activity as antisemitic, would we be seeing more of it? Or has it really been ineffective, and people are not being silenced? You can look at anecdotal cases, but I really don’t know how you measure that.

There is definitely an attempt to chill some of that speech and activism on college campuses — both by people who genuinely believe it’s antisemitic and creating a hostile environment for many Jews on campus, and by others who’ve been doing pro-Israel activism for a couple of decades, and who now think this is a more effective approach to achieve those goals.

Last month we saw a media cycle erupt over a commencement speech delivered at CUNY Law School by Fatima Mohammed, in which she criticized Israel and Zionism, in the context of listing a number of forms of oppression and oppressive bodies. It fed into this longer-running narrative about how CUNY is the most antisemitic university in the United States, with one of its professors even claiming that the school has been working to “expunge all Jews from its senior leadership.” Can you talk about what you’re seeing at CUNY, and how it fits into the bigger picture of the campus antisemitism debate?

CUNY is a curious case for a number of reasons. It is probably the largest, most influential working-class higher education system in the country. There’s a lot of lore around its Jewish history — [it produced] a lot of Jewish Nobel Prize winners from back when there were quotas at Ivy League universities. It’s in New York City, which is still the center of Jewish life in the United States. It is also a sprawling institution with a lot of different bureaucracies within bureaucracies, and it’s really hard to tease out what is going on there with antisemitism.

There have been some cases of antisemitism that seemed to have little or nothing to do with Israel, or if they do, the allegations are, at least on the face of it, antisemitic. It’s a huge institution, a lot of Jewish students, a lot of non-Jewish students, and there are some of these conflicts.

But then there’s the Israel piece, and it’s been driven by a combination of the national organizations we see doing this on every campus, and also by some specific professors and faculty who have a variety of grievances against CUNY — some about Israel, some about what they consider antisemitism, some about other things. There’s also a labor component to this — the [anti-union] National Right to Work [Legal Defense] Foundation has been sending out press releases about antisemitism at CUNY, accusing the faculty union of antisemitism, basically with the goal of, if not decertifying the union, then getting a court to overturn New York state laws around participation in unions.

There’s a lot of layers, and that’s part of what makes it hard to decipher what is actually happening. The current case feels like the culmination of a couple of years of this narrative that there is a mounting crisis of antisemitism at CUNY.

It’s really stunning to see [the reaction to] this speech. Fatima Mohammed certainly uses very strong language to denounce Israel, but the speech is not exclusively about Israel, and I don’t think it was stronger language than what we’ve seen at CUNY Law in the past couple of years. She also accused LexisNexis [a software company that collaborated with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)], ICE, and the NYPD of being “fascist.” It touched on a lot of issues. Yet now there’s this huge scandal, you have members of Congress making statements, there’s [proposed] legislation to defund CUNY on the basis it’s supposedly antisemitic.

I don’t know exactly what made this the trigger, other than the pressure on the institution leading up to this. And a lot of the people who consider this rhetoric to be antisemitic are also skeptical of public education writ large, especially when it’s meant to serve poor and working-class folks. CUNY is not an elite institution. So it was a perfect storm that subjected this recent law graduate to a flurry of harassment and criticism.

Do you see an effort by pro-Israel media and national organizations to paint other college campuses as equally susceptible to antisemitism as they believe CUNY is?

CUNY is a unique target, but if this bill to defund antisemitic institutions of higher education gets passed on the basis of people’s concerns about CUNY, there’s no reason to think that would not be applied to other institutions.

That said, there’s a lot of crossover at CUNY between New York City activists and students, especially on Israel-Palestine. Some of that is because the student body is made up of a lot of first- or second-generation immigrants, folks from the Middle East, where Palestine is a really potent advocacy priority. That can get lost [in the coverage] — people say, “Why are they focusing on Israel? It must be because they’re obsessed with Jews or because they’re antisemitic.”

But the tactics that you see used at one school can be used elsewhere. This all took place right after the White House national antisemitism strategy was released, and we saw a lot of people say they should implement it at CUNY. So I think the idea is that if [e.g. national Jewish organizations] are able to address what they see as antisemitism at CUNY with these forceful measures, there’s no reason to expect that would be limited to CUNY.

The other thing to remember about CUNY Law is that it’s the only law school in the country where the Jewish Law Students Association is avowedly anti-Zionist. There are lots of Jewish students at CUNY who consider themselves to be Zionists and who support Israel, but there are also a lot who are part of this activism. A lot of the reaction [to Mohammed’s speech] was wondering what the reaction of Jewish students in the class was, and a lot of them are on the record as being supportive of these political positions.

As a reporter covering antisemitism and college campuses, what do you make of the grouping together of, for example, swastikas being scrawled in public places on campus and anti-Zionist activity? Where do you draw the line in trying to separate out these very different incidents?

American Jews by and large report that their largest concern is right-wing antisemitism. This also comes up when you’re on college campuses talking to Jewish students. There are a handful of college campuses where there is really vocal, some might say aggressive, activism around Israel, but there are many more campuses around the country, many of which get very little attention from national Jewish organizations, where students are encountering people who have never met Jews before and are making offensive comments about them, either through ignorance or malice. You’re seeing expressions of religious antisemitism where you have Christian students who might be hostile toward Jews.

And there’s also an upsurge in racist and other offensive rhetoric. When you ask Jewish professionals on campus where this surge in antisemitism is coming from, sometimes they’ll talk about Israel-related activism, but they also talk about the election of Donald Trump and the way that students who might be more conservative to begin with felt empowered to say more outrageous, offensive things in class, online, or at parties.

That is not part of the conversation when we talk about antisemitism on campus — we’re rarely thinking about the idea that students feel more comfortable using racial slurs now. Those are not the same students doing Palestine activism. That makes it really hard to report on college antisemitism in a clear-eyed way, because you have Jewish college students talking about the antisemitism they may experience, and then you have the national Jewish organizations –– which are meeting with university officials and promoting solutions to the federal education department –– talking about something else.

Right after Joe Biden’s election, the Conference of Presidents [of Major American Jewish Organizations] and the Anti-Defamation League sent a joint letter to the Biden administration saying their top priority for his administration is combating antisemitism on college campuses, by which they meant activism targeting Israel that crosses a line into antisemitism. In some ways, that’s divorced from what students are experiencing. It’s important not to dismiss reports of antisemitism on campus just because there’s a political conversation going on around them, but my goal as a journalist is to report exactly what is going on. If an allegation is made, what is all of the information we can get about that incident? Who’s making the allegation? What appears to be the motive?

I do think there’s some parallel in certain types of activism targeting Israel and cases of things that are more obviously antisemitic, in that they may make Jewish students feel uncomfortable. For example, a Palestine solidarity protest outside a Hillel and antisemitic graffiti on a Hillel may have the result of making some Jewish students on that campus feel uncomfortable, but that doesn’t mean they’re both cases of antisemitism in the way that most people understand what antisemitism is. It’s about talking to and listening to Jewish students across the political spectrum on these college campuses and being really concrete with what we’re describing to readers, laying out the facts, and allowing people to make their own assessment.

You mentioned how some organizations present their priorities for tackling antisemitism on campus in such a way that is divorced from what Jewish students are actually experiencing. Is there a case you’ve reported on that you think typifies this disparity between what’s actually happening on campuses, and what the public is being led to believe happens on campuses?

There was one incident at the University of Vermont that caught my eye: an allegation that people had thrown stones at the Hillel on campus. On the face of it, it’s pretty damning — whether it’s a political protest, or antisemitism, or whatever, throwing rocks at the Hillel is going to make Jewish students feel unsafe. The university said they investigated it at the time, and it was just that someone was studying in the Hillel, their friends came by and tried to get their attention, and they were throwing stones at the window.

So that seems like a frivolous allegation, but then the Department of Education found that there was a rowdy group of guys who came to the Hillel and tried to get their friend, who lived inside, to come out and go to a party with them. They were shaking bikes on a bike rack and tossing stones at their friend’s window, and then a different student opened her window — the Hillel is on the first floor and there are dorms above it — and said, “Stop messing with the bikes or I’m going to call the police,” and they shouted at her to ask if she was Jewish.

It doesn’t seem like people came to the Hillel to harass Jews, but they were being rowdy outside and asked someone who upset them if they were Jewish. It’s unsettling. But also — were they drunk? If she said she was Jewish, were they going to follow up with something else? This was presented as a classic and blatant case of antisemitism, but then it turned out to be messy. I think that happens in a lot of cases — a lot of the time we never get the real story behind an incident that is weird and complicated, but it gets wrapped into this narrative that Jewish students are under assault.

What is the biggest misunderstanding or misrepresentation you see in mainstream reporting on campus antisemitism?

A lot of the reporting starts from the premise that antisemitism is surging on college campuses and works back from there. And I think that’s true of antisemitism off of college campuses, but there’s also an entrenched narrative right now in American media that antisemitism is skyrocketing, and then everything is slotted into that.

I had a handful of antisemitic comments made to me when I was a student, but that’s all they were — someone said something weird and off-color, and it wasn’t great. But now these kinds of incidents are slotted into these narratives and viewed as evidence that antisemitism is surging. As we discussed earlier, this is connected to a political project around speech related to Israel on college campuses.

You could write a whole story that doesn’t mention Israel, or Zionism, or activism at all, but if we uncritically accept the premise that this is a uniquely dangerous time for Jewish students on campus — which there isn’t a lot of data behind — it colors reporting in ways that may not be helpful to Jewish students.

The director of development at New York University’s Bronfman Center [which houses NYU’s Hillel chapter] wrote this piece about how Jewish students on campus were afraid to wear Jewish stars, afraid to put up mezuzahs, and when she asked them why and whether they’d experienced antisemitism on campus, they replied that they hadn’t but that they’d seen how bad it is on social media and in articles, and didn’t want to be the victims of that. So uncritically adopting a narrative that things are uniquely bad has consequences. We shouldn’t shy away from talking about and highlighting antisemitism, but we need to be careful about how we discuss trendlines and the historical context.

Are there wider lessons in all of this for how we think and talk about antisemitism?

One of the things I’ve been the most struck by is how personal antisemitism is. That’s probably true of a lot of forms of discrimination, but because most Jews — especially on college campuses — are not identifiably Jewish, we get to choose how we engage with our Judaism on campus. We get to choose who we tell about our Judaism. So people can genuinely experience antisemitism in wildly disparate ways.

For example, I know some Jewish college students who talk about Zionism like Shabbat observance. They say, “I was brought up with this Judaism where Israel was an integral part, and to tell me that I have to set Israel aside if I want to participate in an event on campus would be like telling me that it’s fine if you’re Jewish, but you can’t keep Shabbat, or you can’t eat kosher.” That’s genuine for those students. But there are other Jewish students who tell me that anti-Zionism is integral to their Jewish identity, or at least being critical of Israel is, and so they don’t feel welcome in Jewish spaces on campus. They feel they don’t have a Jewish home on campus, and that’s antisemitic to them.

It’s a reminder that it’s really important not to dismiss those feelings, because it’s easy to do that when we get into the political discussion of saying that of course it’s not antisemitic to exclude someone from your group because they’re Zionist, but then you have a group of Jewish students who feel excluded and say it is antisemitic. It’s an important reminder to try to hear people and hear where they’re coming from. We’re not talking about organizations here — but individuals are usually acting in good faith.

Given that, it’s really hard to make policies that are going to address antisemitism in a way that makes sense for everyone. Because if people do have such disparate experiences of Judaism and antisemitism, how do you tell a university what it should do about it?

Antisemitism looks different for different people, and it’s important to be careful, when you’re trying to apply blanket policies, that we don’t erase that complexity.