More than 70 years after Israel was founded, the old Ashkenazi guard of the Israeli left is still doing everything in its power to prevent Mizrahim and other oppressed groups from taking the reins.

By Lev Grinberg

Give or take a few seats, it seems things will remain much as they were following Election Day on Tuesday, with the right- and left-wing blocs winning a near-identical amount of Knesset seats as they did in the last elections. And yet, despite what looks to be a similar outcome, it is worth examining the shift that has taken place inside what is commonly referred to as the Israeli left over the last few months.

Following the results of the last elections held in April, some of the smaller parties teetering on the brink of extinction sought to save themselves by joining forces with the larger parties. Moshe Kahlon’s centrist Kulanu party became part of Likud, the New Right party morphed into the Union of Right-Wing Parties, the Arab Balad-Ta’al and Hadash-Ra’am parties resuscitated the Joint List, Labor joined up with Orly Levy’s Gesher party (which did not pass the election threshold the last time around), and the left-wing Meretz teamed up with Ehud Barak and Stav Shaffir to form the Democratic Union.

On the center-left, these attempts at survival have led to long-simmering tensions between the old elites and those who want to represent long-oppressed communities in Israel, primarily Mizrahi Israelis.

The fall of the Ashkenazi elite

Following the implosion of the Oslo Accords in 2001, famed Israeli sociologist Baruch Kimmerling published a short book titled “The End of Ashkenazi Hegemony,” detailing the downfall of the Ashkenazi secular elite that had ruled Israel since the first days of the state.

Kimmerling defined the founders of the pre-state Zionist institutions and later on the State of Israel as secular, veteran, Ashkenazi, socialist, and nationalist. This group molded the collective Israeli identity in their image (European, secular and modern), established the ruling Mapai party, controlled the economy, and dominated Israeli culture. All other groups that made up Israeli society were subjugated by this elite, including Arab citizens and ultra-Orthodox Jews.

Jewish immigrants from Arab countries were forced into an Israeli “melting pot,” which compelled them to ditch their Arab culture in order to integrate into society, while being sent to far-flung, undeveloped areas of the new state where they replaced the Palestinians expelled during the 1948 war.

According to Kimmerling, following Oslo, Israeli identity broke down into seven communities: secular Ashkenazim, religious-Zionists, the Ashkenazi ultra-Orthodox, Mizrahim (Jews from Arab and Muslim countries), Jews from the former Soviet Union, Arabs, and Ethiopians. Meanwhile, the end of secular-Western dominance over Israeli identity was the result of three different processes that had taken shape in Israel over the last 50 years. Chief among them was the emergence of a messianic, settler religious-Zionism that replaced the historical role of the Labor movement as the movement that sought to settle the entirety of Land of Israel. As opposed to Labor’s secular settler ideology, the religious-Zionists developed an alternative strategy for the establishment of a settler society steeped in a religious-messianic ethos.

The second change was the mass immigration of Jews from the former USSR in the early 1990s. Unlike immigrants from Arab countries, these new immigrants were accepted into Israeli society without being tossed into the melting pot and forced to shed the culture of their home countries.

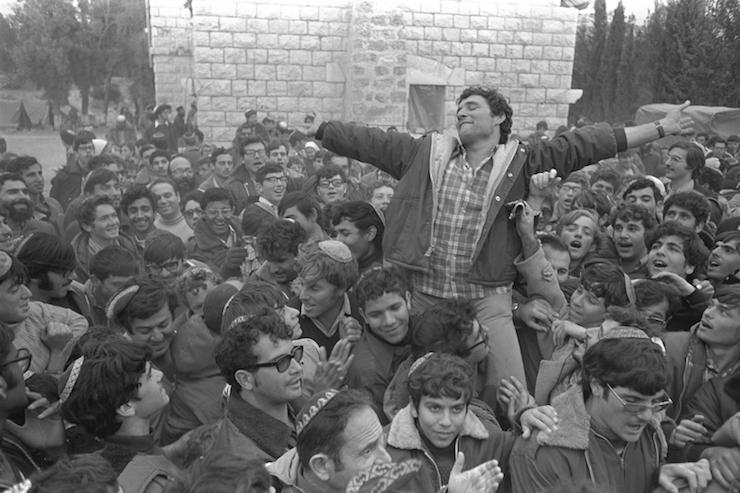

The final change was the attempt by Mizrahim to enter the political arena, which began in earnest in 1984 and culminated with 17 Knesset seats for the Sephardic ultra-Orthodox Shas party in the 1999 elections.

The dissolution of an Israeli collective identity in the ’90s was seen by many as the “end of Zionist ideology.” This lead to the strengthening of so-called “sectorial parties,” which represented the interests of various groups in Israeli society, while the power of larger parties such as Labor and Likud began to dwindle.

The power of the tribe

In 1981, Prime Minister Menachem Begin defeated his contender Shimon Peres by one seat (48-47) in an election cycle that, for the first time in Israeli history, saw the establishment of a left-right tribal dichotomy. Tribalism allows parties to recruit supporters based on a sentiment of belonging to “people like us,” all while sowing hatred for and fear of members of the other tribe. It is also very beneficial to political parties, as it allows them to evade substantive policy debates while re-framing the election as a battle of “us versus them.” It worked in 1981: leftists hated Begin and rightists hated Peres.

Both the left and right have a mythical self-image that is inconsistent with the actual policies of the parties that represent them. The left views itself as a peacemaker, despite the fact that Mapai (the predecessor of the Labor Party) and its political partners were the ones who implemented the occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, East Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights and helped launch the settlement enterprise.

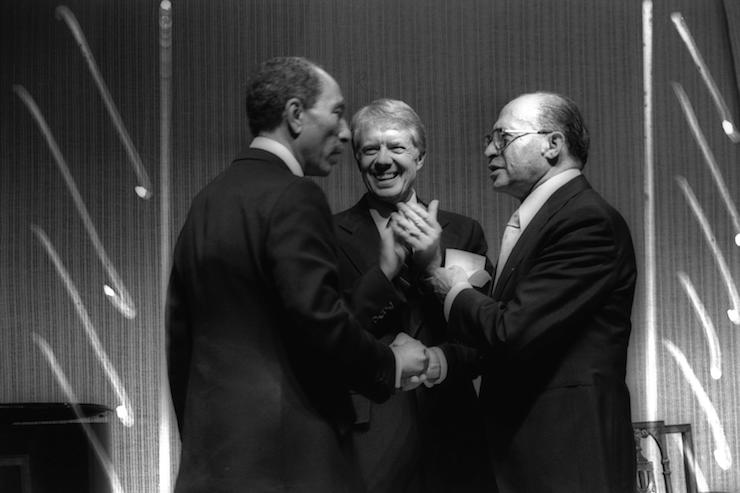

Meanwhile, the right views itself as the protector of the entire Land of Israel, even though it was Begin who made peace with Egypt; withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula and dismantled the settlements there; recognized the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people; and agreed to establish autonomy in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip for a period of five years (the agreement was not realized at the time, although it did serve as the basis for Yitzhak Rabin’s proposals to Yasser Arafat during the Oslo era).

As opposed to Kimmerling, I believe the Oslo Accords were the defining moment that tore apart a collective Israeli identity, which until then revolved around compulsory military service and viewing the Palestinians as a common enemy — the glue that held together the various components of Israeli society. The moment Arafat and Rabin shook hands on the White House lawn, Israeli identity began to splinter, along with the traditional left-right divide.

Parties for everyone — except Mizrahim

The question of Mizrahi representation has been at the forefront of the various election cycles in Israeli history. In 1999, Shas jumped from 10 Knesset seats to 17, while a crop of new Mizrahi leaders began to emerge. Yet those Mizrahi politicians did not form alliances with one another, opting instead to join parties that had been established by Ashkenazim. Mizrahi identity, it turned out, was the only one among many that was seen as illegitimate. This was a time when Russian, ultra-Orthodox, Arab, and religious parties abounded. The Mizrahim, however, were severely criticized whenever their representatives stepped out of line.

Every Mizrahi leader knows that teaming up with another Mizrahi politician means certain political death. This has become evident in last few months, after the left-wing Meretz party was praised for allying itself with hawkish former Prime Minister Ehud Barak — despite the huge ideological gaps between the two.

Meanwhile the union between Labor leader Amir Peretz (who is of Moroccan descent) and Orly Levy, a former member of Knesset, with Avigdor Liberman’s Yisrael Beiteinu who focuses on social issues like public housing, was roundly condemned across the left. Peretz’s decision to choose Levy, a Mizrahi woman, over Meretz (a party dominated by secular Ashkenazim) was too much for the left-wing tribe. The moment he tried to break with the traditional tribal left-right discourse, Peretz was accused of secretly plotting to join a Netanyahu-led coalition on the day after the election.

The lack of any policy debate also explains how both the left and right can continue to appeal to tribalism in order to mobilize voters. Mizrahi identity is seen as a threat to Ashkenazi hegemony precisely because it can serve as a more accepting collective identity than both the secular Israeli identity offered by the left and the nationalistic identity of the right. Mizrahi identity, then, is capable of holding what are perceived as contradictory terms, including Arab identity and Jewish identity, religion and secularism, modernity and tradition. And in doing so, it becomes an inclusive alternative identity for all Israelis. It is also the reason Mizrahi leaders are under unprecedented attack by members of the Ashkenazi elite.

In this context, Avigdor Liberman, who has historically represented Russian-speakers in Israel, has turned into a life preserver that could save the elites from their demise. After rebuffing Netanyahu’s offer to join the ruling coalition following the last elections, Liberman has become a kingmaker who will be able to decide this election’s outcome. This is why much of the left is pinning its hopes on him.

The Russian vote was decisive in deciding elections in the ’90s, but with the resumption of hostilities between Israelis and Palestinians, Russian speakers sided firmly with Likud. Liberman was the first politician to turn hatred of Arabs into a central tool for mobilizing voters in the 2009 elections. It was that hate and incitement that won him 14 seats.

Since then, however, Netanyahu has learned to use anti-Arab racism far better than Liberman, forcing the latter to search for a new kind of hatred that could mobilize voters. He found it in demonizing ultra-Orthodox Jews — a defining feature of the tribal left — which will likely bring him more Knesset seats than the five he won last April. By demanding the establishment of a secular unity government with Likud and the centrist Blue and White, Liberman hopes to elevate Russian-speakers to the same status as that of the veteran Ashkenazi elites.

But tribalism is not a political position — it is a form of political mobilization that is premised on animosity. If Liberman is able to form a secular unity government, it will not only be conservative and capitalistic coalition — it will also reaffirm the legitimacy of Israel’s military control over the Palestinians in the occupied territories. All it will take is for Netanyahu’s right-wing-religious-Haredi bloc to receive fewer than 61 votes on Tuesday.

And while there is an alternative to Liberman’s secular coalition, it is unlikely that the Ashkenazi elites will support it: a coalition that seeks to connect the older elites with groups that were subjugated by those very same elites, including Mizrahim, the ultra-Orthodox, and Palestinian citizens. Yitzhak Rabin was murdered for attempting to create these alliances, and there has never been a leadership brave enough to take the risk since.

This is not a question of mathematics and Knesset seats, but rather of political will. Amir Peretz was violently silenced by the tribal left after explicitly supporting this alternative, Rabin-esque vision. After all, inclusion for other identities has never been part of the center-left’s toolkit when it came to mobilizing voters. Maybe after these elections, the tribe will rethink its strategy.