“Kedma Mizraha: R. Binyamin, Binationalism and Counter-Zionism” (in Hebrew), by Avi-ram Tzoreff, Zalman Shazar Center

I spend too much time on Facebook, where political arguments tend to repeat themselves. A few months ago, a friend posted a quote by Theodor Herzl, considered the father of modern political Zionism, in an attempt to prove Herzl was a liberal humanist. I immediately commented that the man was not only an avowed colonialist, but even defined Zionism as essentially colonial. Indeed, Herzl wrote honestly about the inevitable opposition of the “native population” toward the Jewish settlers in their land, and about the Zionist movement’s need to turn to imperial European powers to overcome this resistance.

In response, a participant in the discussion said that my explanation was anachronistic: Herzl was a product of his time, and what could be easier than criticizing someone who operated 120 years ago? How could he have known that his views would be deemed unacceptable more than a century later?

The expectation that we should refrain from applying today’s ideas and standards to the past is, of course, legitimate. But the vast majority of the time, the rush to justify the words of historical figures operates by a sort of circular logic: if Herzl spoke admiringly of colonialism, the thinking goes, it was probably because it was impossible to speak otherwise at that time, and the proof of this theory is that, after all, he did indeed think this way. We thus need to work harder if we are to faithfully reproduce the full range of ideas in any given period.

Avi-ram Tzoreff’s new book, “Kedma Mizraha: R. Binyamin, Binationalism and Counter-Zionism” (in Hebrew, Zalman Shazar Center) is primarily an effort to do precisely that. It refreshes our historical imagination of Zionism, and in so doing demonstrates how far one could be from the dominant positions that Israelis learn about in school. The book, which grew out of Tzoreff’s well-researched doctoral dissertation, presents with clarity both the intellectual development of its subject and the internal consistency of his ideas.

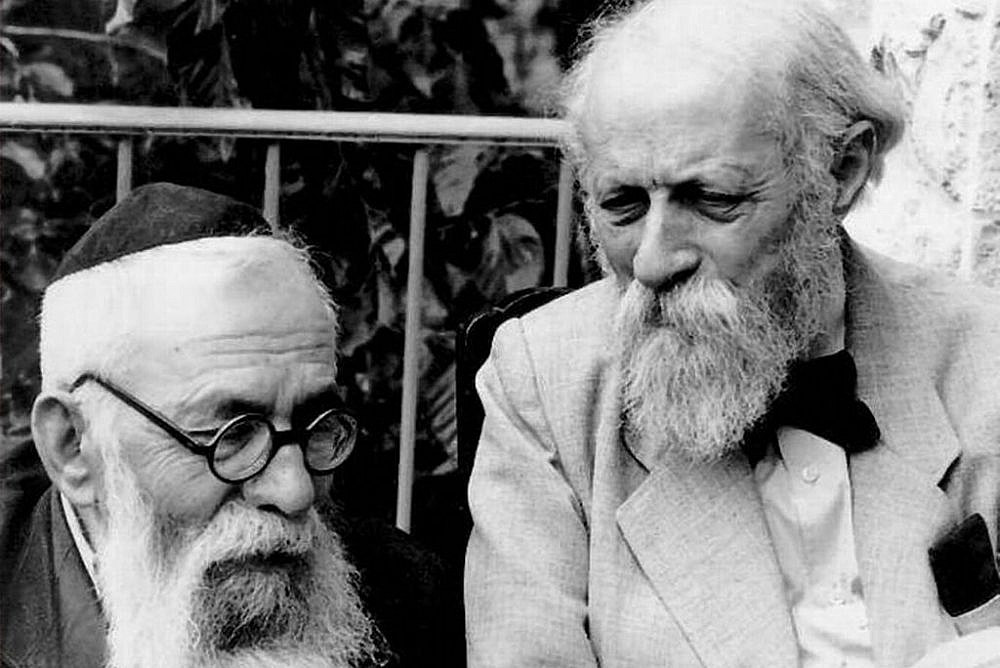

On the face of it, the book is about R. Binyamin — the pen name of Yehoshua Redler-Feldman, a Zionist activist and writer born in 1880 in Galicia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, who arrived in Palestine in 1907 and died in 1957. (The R. stands for Rabbi, which was then a common appellation for East European Jewish men, not a formal title).

However, rather than creating a typical biography structured around Binyamin’s life or attempting to portray him as a role model to be followed, Tzoreff builds his book around Binyamin’s positions on a long series of issues that lay at the core of Zionist discourse in the first half of the 20th century. With this layout, Tzoreff provides the reader with a prism through which to understand the dominant forms of Zionism that ultimately prevailed.

Nationalism as idolatry

Binyamin was a Haredi Jew who defined himself as a Zionist and an admirer of Herzl until the end of his life, largely because of Herzl’s call for Jews to leave Europe and escape murderous antisemitism. In his early years in Palestine, Binyamin was a junior clerk in the Palestine Office, then the central Zionist body that dealt with land acquisition. He also edited, together with Yosef Haim Brenner, a pioneer of modern Hebrew literature, the magazine “Ha’Meorer.” He was a well-known figure among the Zionist leadership, and David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, was among the readers of his articles.

Tzoreff’s book shows that Binyamin cannot be seen as someone who posited a consistent alternative to the dominant trends in Zionism. And yet, given his positions, it is remarkable just how much Binyamin deviated from the mainstream discourse. In contrast with the wide acceptance of a host of ideas among the Zionist leadership — negation of the Jewish diaspora, alienation vis-a-vis Palestinians that morphed into hostile militarism, and racist treatment of Sephardic and Yemenite Jews — Binyamin displayed a radical openness to all these groups.

I personally grew up on images of the backwards, Eastern European Jewish town. To this day, “diasporic” is used as a derogatory term in Hebrew, even to paint Jewish critics of Israeli violence toward Palestinians as cowardly because of this “condition.” But in the Galician town of Zboriv, as Binyamin describes in his memoirs, the Jews lived in the center of the city, on wide streets, and regularly interacted with their neighbors. The Jews were among several local groups that gained autonomy within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and lived in peace before violent conflicts arose from the establishment of nation-states. There was also no requirement for the Jews to give up their traditional beliefs and customs in order to assimilate.

Binyamin perceived nationalism as idolatry — a substitute for accepting the sovereignty of God — and therefore committed much of his life to the realization of Jewish rights in frameworks that were not centered on the sovereign nation-state, first under the Ottoman Empire, and then in Arab-dominated countries in the Middle East beyond the borders of Palestine.

Tzoreff cites the work of Israeli historians Anita Shapira and Dina Porat, who accused Binyamin of being “unrealistic” and “disconnected from reality.” But as Tzoreff makes clear, it was actually the official Zionist leadership that disconnected itself from the horrific reality that was befalling the Jews of Europe.

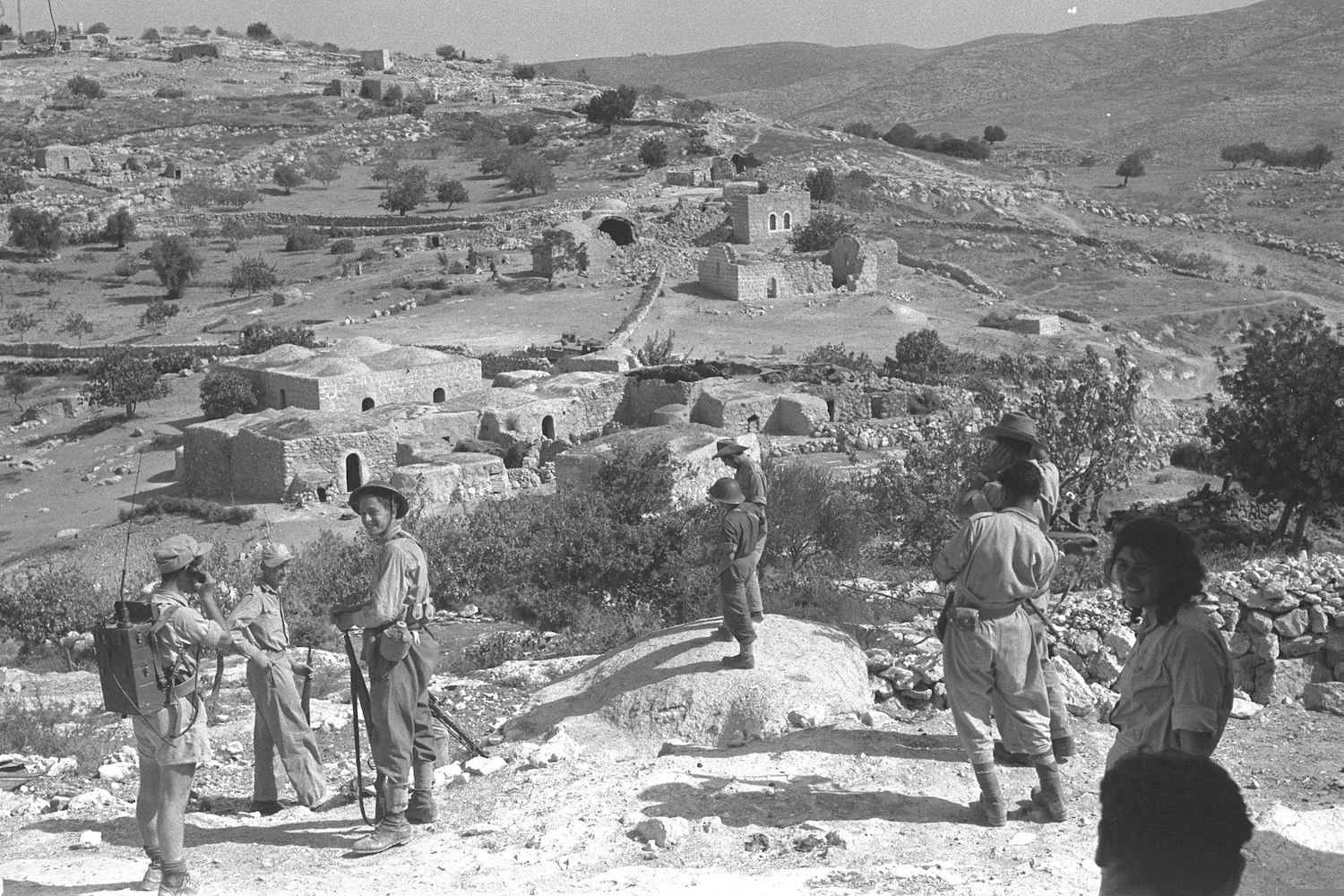

As early as 1942, several months before the Yishuv in Palestine would officially recognize the ongoing Holocaust, Binyamin, then head of “Al Dami” [Not My Blood] movement, warned about the Nazis’ “collective murder” and described it as “a new form that has never existed in the world.” He called to separate the urgent demand to save Jewish lives in Europe from the ambitions of Zionism, which sought, first and foremost, to create a Jewish majority in Palestine and reverse the restrictions imposed by the British Mandate on Jewish immigration in 1939, following the Arab Revolt.

Rather than toe the official Zionist line, Binyamin sought to provide financial and political assistance to Jewish refugees who managed to reach the Soviet Union, and to settle them throughout the Middle East, based on agreements with local governments. Compared to Binyamin’s urgency to save as many Jews as possible, the Zionist leadership’s deep disregard for the diaspora meant it did not prioritize the rescue of European Jews, nor provide the necessary resources to do so.

‘We create the volcano’

Binyamin’s ideas were shaped not only by his openness, but by his consistent willingness to avoid ethnocentric righteousness and his desire to study the social reality that surrounded him. He read Arabic, published articles in Palestinian newspapers, and in his memoirs borrowed motifs from the famed Egyptian writer, Taha Hussein. He opposed the systematic dispossession of Palestinian workers by the Zionist movement, and expressed some understanding for the violent resistance by Palestinians to Zionist plans in their own homeland.

“In order for me to be the ‘majority,’ someone else must be the ‘minority,’ and it is understood that just as I want to be the ‘majority,’ so does that someone else,” wrote Binyamin in 1928. “Here, then, is an open declaration of endless competition, and thus one can only speak of a temporary truce […] but not of true peace and true brotherly unity.”

Unlike so much of the discourse on Palestinian politics today, Binyamin did not give in to the temptation to label Palestinian resistance to Zionism as antisemitic, nor to view Jews in Palestine as victims, as they certainly were in Europe. “In the Diaspora we live on a volcano,” he wrote in 1922, “and here we build on a volcano. More correctly: we ourselves create the volcano, the lava.”

Instead of imposing Jewish sovereignty by force with the support of the British colonial government, Binyamin sought to obtain a new and different “Balfour Declaration” from the Arab people, to replace Britain’s infamous pledge to the Zionist cause in 1917 , and thereby guarantee Jews’ security and rights to life, education, culture, and religion as part of a broader Arab state. The proposal for an autonomous Jewish existence in a larger Arab region was accepted in many Palestinian and Arab circles, including by King Abdullah of Jordan.

Toward the end of Binyamin’s life, while Israeli media presented the 1954 “Lavon Affair” — a false flag operation in which Jewish spies and saboteurs were caught trying to bomb civilian targets in Egypt — as an antisemitic libel, Binyamin again avoided self-righteousness, noting: “The [Israeli] government did not officially announce in clear language that the defendants were not engaged in espionage.”

In contrast to his former friends in Brit Shalom — a political organization of Jewish Zionist intellectuals who, during the British Mandate, believed in binationalism rather than creating a Jewish state — Binyamin remained consistent in calling for the recognition of Palestinian rights and opposing their violent denial, even after the state’s establishment.

As the editor of the magazine Ner (“Candle”), he called throughout the 1950s for the government to allow Palestinian refugees to return to their homeland. Instead of using the term “mistanenim” [literally, infiltrators] — the official designation for refugees who tried to cross the new state’s borders to return — Binyamin referred to them as “ma’apilim,” which had been used for Jews who defied Britain’s immigration restrictions on Palestine in the 1940s. When Binyamin died, in 1957, his funeral was attended by many Arabs whom he had assisted during Israel’s military rule over Palestinian citizens of the state, which lasted between 1948 and 1966.

Rethinking the ‘inevitable’ past

Binyamin’s sensitivity was also expressed toward marginalized Jewish communities. He was involved in bringing Yemenite Jews to Palestine in 1911-12, but unlike some among the Zionist leadership who harbored pseudoscientific racial theories (most prominently, Arthur Ruppin), Binyamin refused to refer to them as “natural workers” who belonged to an inferior Semitic race. Instead, he identified with their religious customs and decried the inadequate accommodations they were given.

Recognizing him as a loyal ally, the Yemenite Association political party chose Binyamin as a candidate for the first Assembly of Representatives, the elected parliamentary assembly of the Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine. Binyamin also worked hard to prevent the marginalization of the Sephardic Jewish community of Palestine, and warned about their lack of political representation in Zionist institutions.

Perhaps even more surprisingly, the Haredi Binyamin was also a supporter of the women’s suffrage movement, and criticized those who chided the women activists to conduct their struggle less aggressively. As Tzoreff points out, Binyamin’s support for women’s suffrage was of a piece with his refusal to vilify the Jewish diaspora: he did not internalize the antisemitic trope of the overly feminized diasporic Jewish man, unlike many Zionists, and was thus unafraid to express support for women’s political movements as a man.

In this, R. Binyamin represented the polar opposite of someone like Yosef Haim Brenner, his erstwhile co-editor, who criticized Jewish men for their “feminine manners” and lack of “manly strength.” It is not difficult to see how, just a few years later, such ideas of Jewish masculinity would pave the way for the Zionist movement’s adoption of hyper-militarism.

Most read on +972

Alongside this radical openness, Binyamin remained firm in many traditional-religious convictions. In one of the last chapters of the book, Tzoreff notes that Binyamin opposed public soccer games on the Sabbath. It is a reminder that his alternative to nationalism and militarism was still based on the preservation of collective observance of Halacha [Jewish law] and the mitzvot — a stance unacceptable to the secular Jewish public.

The purpose of Tzoreff’s book is not to lionize R. Binyamin or gain him new admirers. Rather, in the author’s words, it is to provide “a basis for a critical examination of Zionist history by wandering through its side streets, guided by his writing.” It is still far too common to evade criticizing Zionism’s harm to Palestinians and Mizrahim by referring to the “spirit of the times,” just like my Facebook interlocutor did. Yet the same people would never offer the same defense to historical figures who harmed Jews. They also assume that dominant Zionist figures simply represented the options available in their period, without questioning whether this was indeed the case.

Without learning about figures who imagined radical alternatives, this “inevitable” past makes the present seem just as inevitable. However, recognizing the full extent of Binyamin’s ideas, among many others, enables us to envision a completely different reality here today.

A version of this article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.