Born in 1943 in Rabat, Morocco, Reuven Abergel has been a social and human rights activist in Israel for more than 50 years. He was one of the founders and leaders of the Black Panthers movement in Israel, and continues to be involved in countless social justice struggles.

The following text is taken from The Independent Left in Israel, 1967-1993, a book dedicated to the memory of Israeli left-wing activist Noam Kaminer. Abergel explores the complex and often painful relationship between the Black Panthers, a group of Mizrahi activists hailing from some of the country’s most poverty-stricken areas, and the radical Ashkenazi activists, who despite their politics, were part and parcel of the Israeli establishment.

Author’s note: I would like to thank my dear friend and comrade Itamar Haritan, with whom I have been working for years and who helped me write this text. Itamar interviewed me and wrote an initial draft of the article based on the interview, which we subsequently revised together over numerous conversations.

***

To address the issue of the “independent left” in Israel, and specifically its relationship to the Mizrahi struggle and the Black Panther struggle, one needs to go back to a question that has plagued every attempt to establish a real left movement in this country: how can Ashkenazi [1] activists, many of whom benefited from the Zionist project and whom the Zionist regime considers as their own flesh and blood — how can these activists join together authentically with the victims of that project, the Mizrahim and the Palestinians? What gaps must be bridged? What patterns are preventing real connections from taking hold?

When I think about the period of the Israeli Black Panthers — an important and historic period of both my life and in the struggle against Zionism — I must say that any deep trust between the Panthers and Ashkenazi activists was formed only on the individual level, not on the collective and organizational level. Of course, I would be remiss if I did not mention Dr. Naomi Kies, Hava Fogel, and many others. It is important to understand, however, why the trust that did develop between us and these activists never expanded into a broader collaboration with any of the leftists and left-wing organizations that came to our protests.

Before going any further, I want to clarify that it is not my intention to discount the value of the partnerships. Rather, my goal is to point to the patterns that prevented them from turning into a force that could challenge the political system, both then and now.

Confronting the political system head-on

When we began our struggle as the Black Panther movement, what we actually did was launch a head-on confrontation with the Israeli political system. We didn’t know how to “formulate” texts, organize protests, publish manifestos, or put out press releases. If we wanted to write anything, we would all huddle together over the single typewriter we managed to find and all of us in the group would dictate to one of the activists what to write, letter by letter. As we faced waves of arrests and as police violence intensified during our struggle, we were desperate for any kind of support or even just empathy.

From the very first protest, we were happy to see groups of Ashkenazim coming to support and identify with us. We would see people who we later found out were famous, some of whom were an integral part of the Zionist establishment that was founded on the divvying up of the spoils of the 1948 war: Amos Kenan, Haim Gouri, Baruch Nadel, Dahn Ben-Amotz, Nathan Yellin-Mor, and many others.

There were journalists, writers, poets, university students — all of whom called themselves “leftists;” people who had been members of pre-state Zionist militias and were now coming to our protests. We started to understand that though they may have been from the other side, and though they were the elites, they nonetheless came to identify with us. That was meaningful. First of all, they made our protests safer in a concrete way: Professor So-and-So is here, so all of a sudden, the police are on their best behavior. Their very presence deterred the police from behaving as they usually did, keeping the police violence tamped down and loaded in the chamber. But when those professors moved aside, we got the full brunt of their bottled-up aggression, with interest.

In the first Black Panther protest on March 3, 1971, the one where we demanded the release of those who were arrested in the police raids that took place the night before, the mayor of Jerusalem at the time, Teddy Kollek, shouted at us “Punks, get off the lawn!” From there, we marched to the Russian Compound and demanded that everyone be released. As we were doing that, the Ashkenazim who were with us at the protest started negotiating with the police. The senior officers were respectful and respectable toward them, they even wanted to receive a delegation of Panthers and Ashkenazi supporters.

And lo and behold: The police, who had been persecuting us, abusing us, putting us in jail and juvenile institutions for our entire lives, suddenly turned friendly, accepting our demands and releasing the people they arrested. The Ashkenazim’s support went way beyond their attendance at the protests, though. They organized support events in Tel Aviv’s Tamar movie theater and at Hebrew University’s Givat Ram campus, including at the Weiss Auditorium, which they filled to capacity. They connected us to printers that they knew, and they printed things for us for free. That way we could print membership cards, and print the Black Panther symbols on our shirts. They also helped organize some of the delegations abroad. Because of all this help, little by little we started trusting these people and bringing them in.

Though we were happy to get this help from our Ashkenazi supporters, their presence was confusing. On the one hand, they offered us support in our struggle against the establishment, but on the other hand it was still clear to us that they were the establishment’s own flesh and blood. In the support events that they organized for us, we saw the power and privilege of the people they invited. They joined our protests from a position of strength: it was clear that they knew what they were about; some of them knew they were “anti-Zionists.” They could write declarations and formulate manifestos, all while the only thing that was clear to us Panthers was that our life was busted. We saw how the establishment watched over them to make sure they didn’t get hurt: even those few leftists who managed to catch a few police beatings, and were even arrested, eventually found their way back to their families. Their life went back to its normal course, it was not derailed. They went back to their studies and their jobs with no criminal record whatsoever.

It’s not as if I expected them to sleep on a mattress on the floor like I did, in a room overflowing with kids, with no infrastructure, electricity or running water; it’s not like I wanted the police to stand outside their house and conduct constant searches trying to frame them like they did to us; but these gaps — the economic gaps, the gap in the ability to express oneself, and the gap in the way the establishment treated us and them — all these made us ask ourselves whether they were really with us in the struggle to divide the cake up equally, or whether they wanted to have their cake and eat it too.

They come to help us push off, but they end up capsizing the boat

In fact, it wasn’t long before we identified problematic patterns of behavior in the way these leftist activists related to us. Many of them had an attitude that said that they supposedly have an “ideology” and an “agenda” while we don’t; they made us feel that “we know better than you what needs to be done for you.” Obviously we wanted help formulating our thoughts and we wanted to hear their opinion, but we felt that they didn’t just want to help. They wanted to tell us what to think and what to believe. One time, and this I’ll never forget, the Jerusalemite leftist university students insisted on joining our closed meetings, our Panthers-only meetings where we worked out disagreements amongst ourselves. They wanted to be involved in the entire process and thought that we were ingrates for refusing to let them participate.

These university students, who had partnered with us to form this movement and who had stood by us, were now suddenly asking for their “fee”; they argued that they were as important to the movement as I or other Panthers were. I considered this to be pure arrogance – “I helped you put together a document and now I own you.” Things came to blows, and only then did they try to act like they understood what the problem was. This is like if I had a boat, and I was trying to get out to sea but needed someone to shove me off from the pier. Then let’s say I found two people to help me, but in the process of helping me they tried to jump in the boat themselves and eventually capsized it. Thanks for the push, but the rowing we can do ourselves!

What would have happened if we had agreed to have those students join our meetings and run our movement? We don’t need to leave it to the imagination, since we know what happened to the Black Panthers in Tel Aviv. There, the Panthers decided to bring the leftists into their closed discussions, and suddenly their entire message changed. Our original newspaper, “The Black Panthers Speak,” was in our own language. We put our heart and soul into each article, and only there would you be able to find us expressing ourselves in in our own words.

In contrast, the Tel Aviv newspaper became a “leftist” newspaper — suddenly they started talking about “cooperation amongst all the workers of the world” and so on; this was the language of the Communist Party that had nothing to do with our struggle. We, the Panthers, did not see ourselves as “workers” belonging to all the workers of the world, but rather as a group struggling against oppression, racism and discrimination. And these slogans about “cooperation amongst all the workers of the world” had no relevance to the Panthers’ struggle.

Workers? Our parents had been out of work from the moment they came here, and so were we! That doesn’t mean that we rejected connections and solidarity amongst oppressed groups and struggles around the world. When we saw the African-Americans in the United States, we saw ourselves. We identified so much with them that we were inspired to follow their example by giving our movement the same name as theirs. It was the same thing when we saw Black people in South Africa and the struggle against apartheid; we saw ourselves. We just didn’t connect with the Bolshevik slogans.

Though the incidents discussed above relate to specific activists and groups, that same basic pattern held true for most leftists we encountered. As a rule, we felt that when an Ashkenazi activist attended a protest, it was more likely than not that they were on some kind of “mission” — trying to influence, channel, impose or lead something in one direction or another, rather than just being there to support us. We felt that many activists had an expectation that they would be involved in leading the movement, as if their support was being given with strings attached, strings that were supposed to be hidden but were actually quite visible.

We learned as we went along which leftist activists we wanted to work and which we did not. We weren’t interested in what group they belonged to, what their platform was or whether they were Zionists or anti-Zionists. Over the years, we did get a better understanding of the differences between leftist groups — the anti-Zionists, the Zionists, the communists, the anarchists, and so on; but as young Black Panthers in Musrara [the Jerusalem neighborhood where the Panthers were formed], these groups’ platforms were not important to us.

Only two things were clear to us: first, all these leftist activists were Ashkenazi, the establishment’s own flesh and blood, people that the police handle with kid gloves regardless of their group’s platform; and second, that some of them were our friends, they stood beside us and tried to use their privileges to help, while others were there for their own reasons, using their power to impose their perspectives and thinking they knew better than us what needed to be done.

The Mizrahi struggle is ‘social,’ the Palestinian struggle is ‘political’

Another pattern we encountered was that leftist activists, Zionists as well as non-Zionists, treated the Palestinian struggle in a completely different way than they did our struggle: The Black Panther struggle they saw as “social,” whereas the Palestinian struggle they saw as “political.” We faced this pattern everywhere. For example, we never saw any “human rights defenders” in our neighborhoods, checking on our wellbeing or asking “why are you being arrested?” despite the fact that they arrested dozens or hundreds of us, despite the fact that they beat us and exhausted entire families with legal expenses and harassment.

There was a period in Israel’s history when the courts all worked as a team to send Mizrahim away to Eilat, to “exile” them as part of a sentence for charges of assault or disorderly conduct, which usually happened at employment offices or other places where they mistreated and humiliated people who were looking for work and who would be turned away empty-handed. Those people were sentenced to stay in Eilat and help establish the city there. They also established many jails and juvenile institutions to lock up our young people, and we never saw Physicians for Human Rights or other human rights defenders running to defend our rights when we were in trouble, whether before the Black Panthers struggle or after it — and to this very day. We were and continue to be totally exposed to state violence. At the same time, leftist organizations made sure that Palestinian activists always had lawyers, petitions of support, and articles in major English-language newspapers abroad — things we never saw them do for us.

This pattern was also reflected in documentation. Many leftist activists documented the Palestinian struggle; they wrote articles and books about it, made movies about it, and so on. But they never once bothered to write about our struggle or help us document it, to take down the stories of victims of our oppression, whether ours or our parents’. We saw how they visited Palestinians in prison and took down their testimonies as part of supporting their legal defense, or for documentation purposes — while our prisoners were left isolated and nameless. Even when it comes to the kidnapping of the Yemenite children and the ringworm radiation experiments, which any person in the world would call war crimes, to this day the left has yet to dedicate any meaningful amount of their writing to these topics.

This pattern has become more sophisticated over time. At one point leftist activists started coming to protests with cameras and audio recording equipment. We saw them passing around cameras and recorders to Palestinians, providing them with crash courses on how to do journalism using these tools. We saw how they allowed Palestinians to have access to the materials they gathered and to use them for their struggle. In their activism with us, on the other hand, they would record and photograph us without ever offering to teach us how to use these tools ourselves, and it goes without saying that they never thought to raise money to buy some of this equipment for us to use. They never gave us access to their recordings and photographs, even though they were of our own struggle, even after many years, even when we offered them money. In the last few years, we contacted many people who are in possession of such materials, and they didn’t even agree to show them to us. To this day, there are only a handful of Black Panthers that have any documentary material from the struggle.

In the years of the Black Panther struggle, the left’s clear preference for the Palestinian struggle, as well as their willingness to offer important resources to them and not to us, created a chasm of mistrust between us and the leftist organizations. We would go into every protest knowing that we would get hurt, that we would be arrested and possibly jailed for long periods — and that most of our leftist friends would not be there for us, would not get us lawyers and would not document what was being done to us. We heard them make many a statement about human rights and justice for all, but the different approaches they took to the Palestinian and Mizrahi struggles sent us a clear message: what they say is not necessarily what they actually believe.

For the first time, we saw ourselves as leaders

In my view, this preferential approach of most leftist activists to the Palestinian struggle, as well as the constant attempts to “channel” our struggle in different directions, are two behavioral patterns that stem from the influence of the Zionist regime. This regime’s relationship to Palestinians was always as an enemy — a dangerous enemy, but also a sovereign enemy, capable of independent thinking and existing apart from the regime. In contrast, their view of Jews from Islamic countries has always been that they are an “empty cart,” [2] human material that must be “molded” and that therefore needs to be defined by an external authority. This human material is not able to define itself and its path forward, so it always needs to be under control and supervision.

This same regime’s division of the spoils of the 1948 war, and its enormous efforts to erase our tradition and culture, may be seen as a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. The establishment did its best to turn us into uneducated criminals with no future, people who have no clue about where they’re going or where they’ll be tomorrow. That was the state we were in when the leftists found us. That was in the state in which we found ourselves in 1971, in the first protest of the Black Panthers.

And this is where the leftists made their tragic mistake. The real revolution of the Black Panthers was that for the first time, we saw ourselves as leaders, as people that can change the reality. After our first protest, we realized that our struggle is not just against the establishment, but also for the possibility of even being able to imagine a future, to articulate our demands and to express ourselves. The most radical and anti-Zionist thing that those activists could have done when we launched our confrontation with the establishment was to stand behind our leadership, and say loudly and clearly that these young people are not an “empty cart,” that they are human beings fighting an oppressive regime.

Instead of affirming us, most activists’ attitude was that they needed to teach us about anti-Zionist ideology — meaning theories, concepts and texts, those very things that the Zionist movement made accessible to them through youth movements, clubs, universities, schools and coffee shops that only certain people, Ashkenazim, were able to attend. We never set foot in these places, and for an obvious reason: There was apartheid, racist separation between the different groups, “them there and us here.” [3] Because we couldn’t speak their language, they thought we were lacking in ideology, that we were non-political, a struggle in search of leaders.

Who is a true anti-Zionist, and what is authentic anti-Zionist ideology? The Ashkenazi leftists’ answer to this question is exactly what distorted their vision of who we were. They put more faith in their theories than in our pain to lead an anti-Zionist struggle. It’s true, we did not grow up on anti-Zionist “ideology” and we did not call ourselves “anti-Zionists,” but we did not need “ideology” to know that our situation was the Zionist movement’s handiwork. We knew our lives, the streets we survived on, and we knew the pain that both we and our parents felt. It is from these sources that we drew inspiration for our actions. Again and again we came up with creative and subversive ways of expressing this pain to embarrass and challenge the establishment; again and again we put ourselves in a radical, head-on confrontation with the establishment, not because of the right ideology but because of our willingness to cry out about what was happening to us.

The truth is that it was the Zionists themselves who explained to us that we were anti-Zionists. The moment that we chose the name “Black Panthers,” the Israeli establishment understood they were dealing with anti-Zionists, and that’s exactly what Golda [Meir] [4] informed us of when she asked “Why did you call yourselves Black Panthers? They’re Israel-hating antisemites.” Golda’s statement was supported by the Jewish fascists led by Rabbi Meir Kahane [5], who declared us “enemies of the state.” The conflict between us and Kahane’s people escalated to the point of physical violence. All Black Panther actions since the 1970s were seen by the Israeli government as anti-Zionist acts. We quickly realized that whoever struggles for their rights in the State of Israel is necessarily struggling against Zionism, so we could say we were proud anti-Zionists, because Israeli governments throughout the decades have viewed resistance to their policies and decisions as struggles against Zionism.

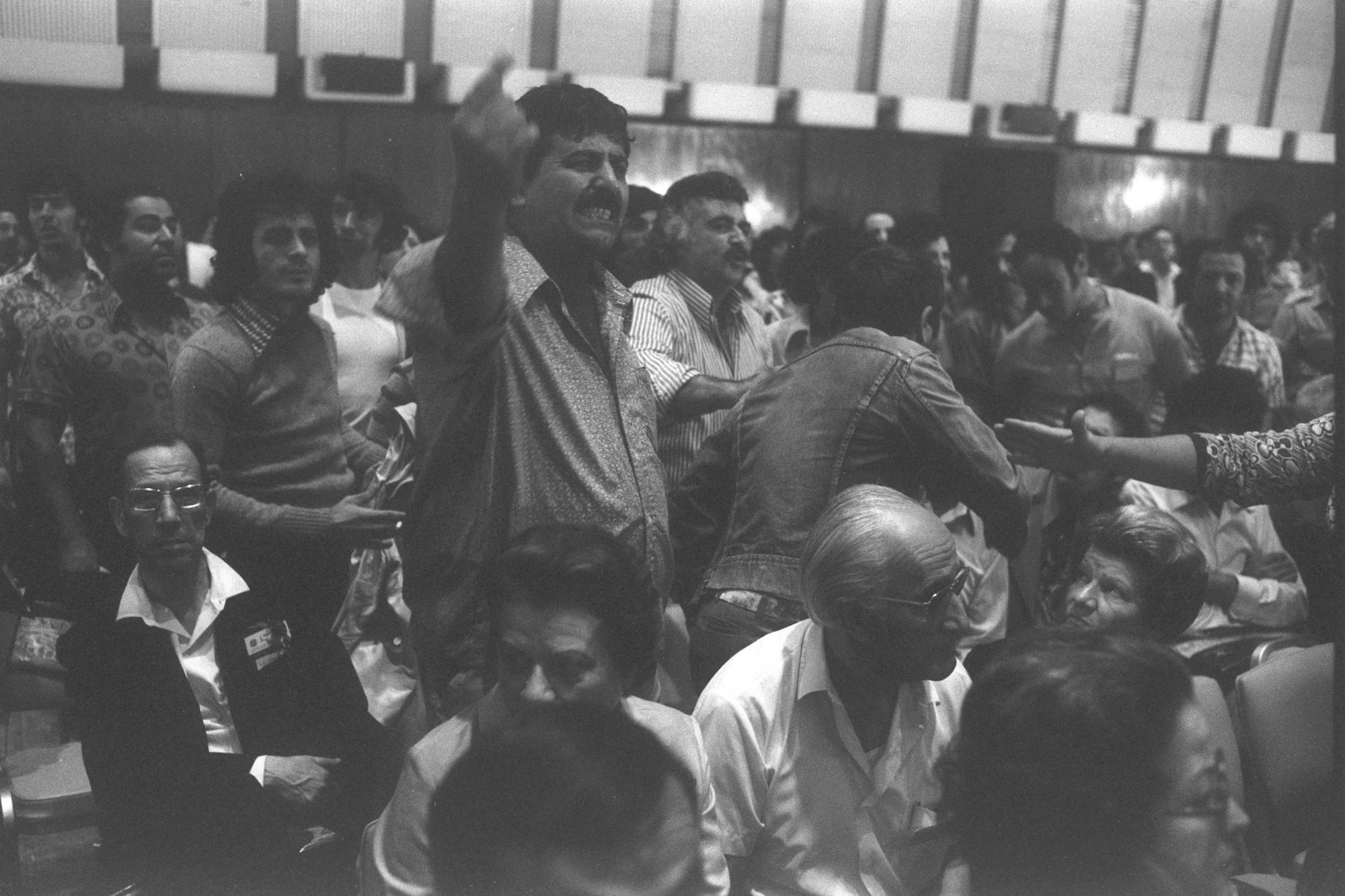

For example, one of our first and most famous actions was a hunger strike at the Western Wall. [6] We didn’t do it because we identified as “anti-Zionists,” but because we wanted to make our case against the state about our situation, and we knew that at the Western Wall the police would be more restrained “because of the sanctity of the place.” When we worked with the leftists to protest the Zionist Federation conference in 1972, the newspapers reported that there were Panthers who were planning to throw Molotov cocktails. We wanted to confront the Zionist Federation — not because we identified as “anti-Zionists,” but because we wanted to confront the people who sealed our fates in this country, and to force them to be accountable to us for the first time. Though leftist groups organized the protest with us and participated in it, none of the Ashkenazi leftist groups took such drastic measures, and it goes without saying that the police beat us to a pulp while more or less leaving them alone.

You can also see our assertive attitude in the movements that came after the Panthers: the Tents Movement (some of whom were young Panthers), led by Yamin Swissa, sent a letter to the President of the Soviet Union to ask him to stop the Jewish migration to Israel from Russia, arguing that these immigrants were receiving apartments and jobs from the Israeli government, all while the state had never supported or funded our absorption in this country in the same way. We knew that someone would have to pay for having a million people come to this country, and that it’s always the development towns and poor neighborhoods that pay the price. Opposing Jewish immigration, which is one of the core pillars of the Zionist movement, is clearly an anti-Zionist act, despite the fact that it was never declared “anti-Zionist.”

Our relationship with the Palestinians was not a product of anti-Zionist ideology either. Long before we met the leftists, we saw Palestinians as neighbors and partners. In East Jerusalem, after the border opened in 1967, we established joint businesses, music clubs, market stalls and other ventures with Palestinians. When we launched our struggle, it was clear to us that we wanted to connect to the Palestinian struggle. We wanted to connect with every oppressed group, no matter how large or small, and we saw the Palestinians as a huge group that was oppressed by the same forces oppressing us. Many young Palestinians in East Jerusalem even joined the Black Panther struggle and the protests, and stood by us as our friends throughout that time. In the 1970s, we met openly with the Palestinian leadership in France, which was a violation of Israeli law at the time.

We were not deterred by the image that they tried to pin on us, saying that we were Israel-haters and aiding our enemies. We were not deterred because we thought that Jews from Arab and Muslim countries had no greater enemy than the criminal policies enacted against us by every Israeli government for decades. Later, there were Panthers who met with [Palestine Liberation Organization leader] Yasser Arafat — including then-Knesset member Charlie Biton. I myself met with Arafat in the Muqata’a. [7] It is precisely because of our constant efforts to connect to the Palestinian struggle that we felt so betrayed by the Ashkenazi left’s persistent devaluation of the Mizrahi struggle and preference for the Palestinian struggle.

The Panthers’ practical ideology, our head-on confrontation with the Zionist movement, our relationship with the Palestinians and the establishment’s own view that our struggle is anti-Zionist — all of these combined were not enough to convince the leftist anti-Zionist groups that we had an “ideology.” This fact begs a question: What is the point of “ideology,” if its entire purpose is to separate those who attended university from those who did not? Those who read the right books from those who did not? It goes without saying that books and theories can add to any struggle, but the pain is what needs to lead the struggle, and to express rage and pain you don’t need to put it under the heading of “ideology.”

The Black Panthers’ ideology was the pain, the rage and the anger in the face of an incomprehensible reality. The feelings that this reality creates are an enormous energetic bomb that does not require an “ideological” fuse. It is an anti-Zionist bomb by its very nature, because anyone who demands their rights in this country is anti-Zionist by definition. The real problem is that the leftist groups did not see our rage and pain as the thing that needed to lead the struggle. Instead, they saw us as raw materials that they needed to mold and restrain.

The pain is the same pain

The above description still applies to what happens in these struggles today. Time after time, these patterns are still preventing the emergence in this country of a left that is truly independent of Zionism. When all is said and done, the leftist groups have failed to foster true cooperation between three groups, Ashkenazim, Palestinians and Mizrahim — among other things because true broad-based Ashkenazi-Mizrahi cooperation never took off. The Mizrahi pain is the same pain, though nowadays the establishment is able to channel part of it toward a kind of fascism and racism that is unlike anything we ever encountered in the Black Panther era. Instead of seeing our pain and joining our struggle to promote cooperation, the left continues to see Mizrahim as an “empty cart.” Struggles for public housing, for recognition of the Yemenite Children Affair and the ringworm radiation experiments, for changes in the jurisdictional boundaries of regional councils, against racist tracking in the education system — all these receive negligible support from those who call themselves “left” in Israel.

Meanwhile, this “left” repeats empty slogans that repel these groups from each other and that serve the system. The fact that you say to me “You’re right-wing, you’re from the poor neighborhoods, you’re a fascist,” — you already automatically separate me from you. The left’s attitude toward us has always been that “You’re a group that needs to be grateful that you even exist.” That is why I argue, and have argued for years, that there has never been a true left movement in Israel, because the leftist groups that I described stayed trapped in the patterns of the historic Mapai party,[8] whose DNA was inherited by the fascist and capitalist right of today, the same song with a different title. What is called “right” and “left” in Israel are actually inseparable parts of the same establishment. It is really important to understand this. The real difference is not between right and left, but between the establishment that preserves the privileges of the “white tribe,” and anyone who challenges that establishment.

Despite the problematic patterns that shaped the relationship between the leftist groups and the Black Panther struggle, there were a few glimpses of a different possibility, of real solidarity. These glimpses emerged on the individual level, with specific activists who were able to put aside Zionism’s dictates. I mentioned Hava Fogel and Naomi Kiss in the beginning, and now I would like to mention Reuven and Noam Kaminer. I was Reuven’s friend before the Black Panthers. We met in Musrara. There was a Communist Party branch office in Heleni Hamalka street. We would drop by there as youngsters; it was one of the few places where we could go out, have some tea and cookies, maybe see a movie about Lenin and the Bolshevik revolution or attend a lecture. We didn’t even have to pay! Reuven was there and would invite us to events, but he never imposed himself, he never forced us to go to a meeting or anything like that. For us, it was about having some down time, not political activism, but it created a connection between us.

After that, I met with Reuven many times, and later with his son Noam and with his grandson as well. These meetings were always warm and authentic, and I never felt there was any hidden agenda or an air of superiority. Like other Ashkenazi activists, Reuven and Noam were present in many Black Panther protests; the important thing is that they were not the kind of people that would preach about their “ideology” and act like it was more important than anyone else’s opinion. What was important for them was to be there, nothing more, as opposed to others who were “on a mission” during the protests and actions.

My many years of friendship with Ashkenazi activists who were able to break through the barrier of superiority clarified for me and for others that the Mizrahi struggle is against the hegemony, against the structure that the “white tribe” created here to maintain their division of the spoils, and not against Ashkenazim as a group. When you fight oppression, you are also fighting to free your oppressor from their patterns. Those among the oppressors who manage to develop a true desire to become free of those patterns are a rare and precious few, and every leftist movement that wants to be truly independent must liberate itself from these patterns and see the oppressed who struggle for their rights as a “full cart.”

________________________________________________________________________

[1] Ashkenazi is a term that in Israel has come to refer to Jews whose ancestors came Europe. Ashkenaz is a biblical figure whose descendants are identified with Germans in the medieval Jewish tradition.

[2] In the Talmud, there is a halachic principle in which a camel puling an empty cart must make way for a camel pulling a cart loaded with goods. This principle became part of Israeli popular culture after a meeting between Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and Rabbi Avrohom Yeshaya Karelitz (the “Chazon Ish”), in which the latter reportedly described secular Israelis as an “empty cart” that must make way for religious Israelis, the “full cart.” Religious Israelis bear the burden of maintaining Jewish tradition, and therefore must be prioritized in matters of policy.

[3] “Them there and us here” is a slogan that became popular in the right-wing opposition to the Oslo Accords. It was coined by the extreme right-wing politician and ex-military figure Rechavam Ze’evi, who used the slogan to support the idea of population transfer, or the forcible expulsion of Palestinians from historic Palestine. Since then, the term has come to broadly denote the idea of separation between Palestinians and Israelis.

[4] Golda Meir, Israel’s Prime Minister at the time of the Black Panther struggle.

[5] Rabbi Meir Kahane was an Israeli-American orthodox rabbi and ultra-nationalist politician whose party, Kach, was banned from the Knesset for being racist and anti-democratic. He supported restricting democracy to Israel’s Jewish citizens, enforcing Jewish religious law as opposed to secular law, annexing the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and “transferring” the Palestinian population. He was convicted of manufacturing explosives in New York in 1971. Many present-day Israeli right-wing groups openly draw their inspiration from his racist views.

[6] The Western Wall is a remnant of the Second Temple, and a holy site to both Jews and Muslims.

[7] The Muqata’a (المقاطعة) is the headquarters of the Palestinian National Authority in Ramallah.

[8] Mapai is the Hebrew acronym for The Workers’ Party of the Land of Israel. Mapai was the dominant force in Zionist politics from the early 1930s and until 1977 when Likud took power. It is the precursor to the Israeli Labor Party.