Frederik Willem de Klerk, the last president of apartheid South Africa, died on Nov. 11 at the age of 85. In a video released after his death, a frail de Klerk sought to set the record straight regarding criticisms that he had continued to justify apartheid’s existence after its demise in 1994. His voice shaking, the former statesman made an unequivocal apology “for the pain, and the hurt, and the indignity, and the damage that apartheid has done to Black, brown, and Indians in South Africa.”

While admitting he had once been a defender of what he called “separate development,” de Klerk insisted that his views had “changed completely” since the early 1980s. “It was as if I had a conversion, and in my heart of hearts, realized that apartheid was wrong. I realized that we had arrived at a place which was morally unjustifiable.” That conversion, he added, motivated him to negotiate with the African National Congress (ANC) and to oversee the country’s transition into a constitutional democracy after more than 40 years of white minority rule.

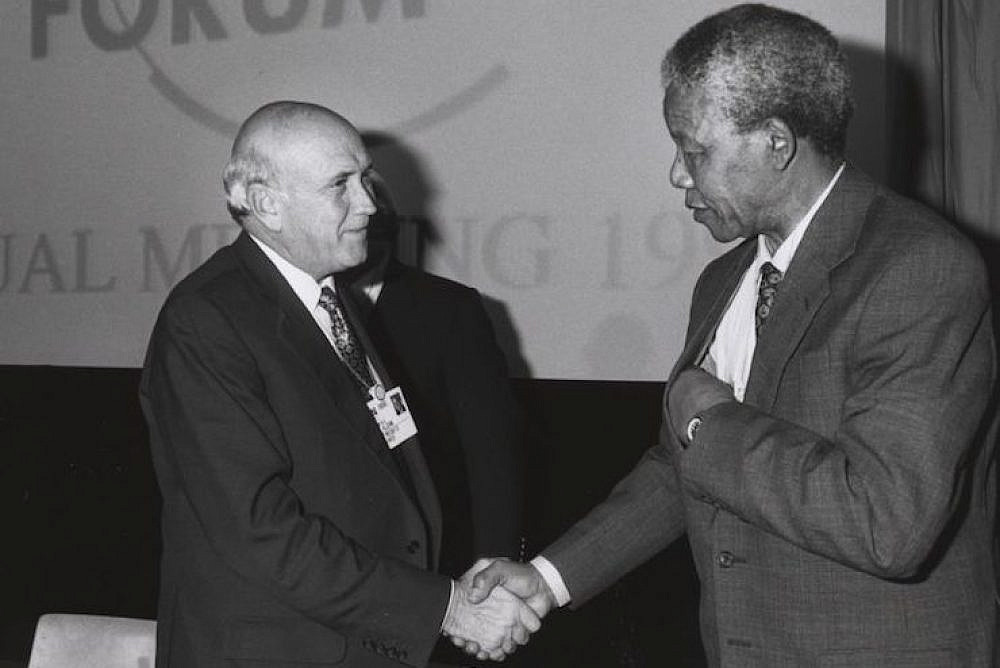

De Klerk’s death has sparked much debate among South Africans about his legacy, a conversation that is worth following in its own right. But it has also revived familiar murmurs in Israel-Palestine. For years it has been common to hear the lament, “Where is Israel’s de Klerk? Where is Palestine’s Mandela?” implying that, if the two societies could simply produce such visionary leaders, they could resolve the conflict between them.

This great man theory of history conveniently erases the factors that brought about de Klerk’s “conversion.” By the time he took the helm of the National Party in 1989, de Klerk — a shrewd politician with a conservative reputation — realized that the odds were growing against white minority rule. Civil disobedience, armed violence, cultural boycotts, and international sanctions were crippling Pretoria’s hold on power. Global public opinion had branded South Africa the “skunk of the world,” and the United States and United Kingdom — once stellar allies of the white government — were ramping up political and economic pressure to end apartheid.

It was this strategic calculation, far more than moralism, that compelled de Klerk to try to redesign South Africa’s regime on terms favorable to the white minority. When the National Party entered negotiations with the ANC, their initial desire was for a power-sharing agreement that would reserve special privileges and vetoes for whites. Along with its direct crackdowns during that period, the government waged a covert war against the ANC by supporting the rival Inkatha Freedom Party to weaken Black unity around the liberation struggle.

When the National Party’s proposals were deemed unacceptable by both the ANC and international community, and its “divide and conquer” tactics failed to break the anti-apartheid movement, de Klerk had little choice but to accept the principle of “one man, one vote.”

The key lesson from this trajectory is that history did not wait for de Klerk to take the reins; it had to force de Klerk into being. It took a mass movement that combined popular, military, and solidarity tactics to turn the power balance against apartheid, making it unsustainable for white South African leaders like de Klerk to support anything but the dismantlement of the racist regime. History, too, had to take the side of individuals like Nelson Mandela, a lawyer turned military leader who was derided for decades as a “terrorist,” yet was ultimately hailed as a freedom fighter.

The imperfect but striking parallels between South Africa and Israel-Palestine are becoming widely known and accepted. Yet one of the biggest discrepancies between the two struggles is that while governments gradually mobilized to end apartheid in the former, they have effectively acquiesced to, if not openly embraced, apartheid in the latter. Even during the Oslo “peace process,” actors like the U.S. and EU consistently prioritized Israel’s interests, ossifying the power asymmetry that would turn the accords into a prison, rather than an engine, for Palestinian liberation. This enabled Israeli leaders like Yitzhak Rabin to reshape the occupation to their liking, without ever having to rectify its moral injustice.

The exception to Israeli apartheid derives from various factors — but those reasons have been heard before. Like Jewish-Israelis, many white South Africans were convinced that the fall of the regime would bring about their destruction, and presented themselves as a bulwark of democracy and Western civilization in a dangerous neighborhood. At some point, however, the world could no longer buy into such justifications for upholding racial supremacy. If de Klerk’s life can teach us anything in Israel-Palestine, it is that we cannot expect apartheid defenders to change their minds of their own accords; they must be made to do so.

From “The Landline,” +972’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.