Twenty-five years ago this past weekend, a large-scale popular uprising by Palestinians began against Israel’s then 20-year-old military occupation of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza. Sparked by an incident in which four Palestinians were hit and killed by an Israeli driving in Gaza on December 8, 1987, Palestinian frustration at living under repressive Israeli military rule and Israel’s growing colonial settlement enterprise erupted, grabbing international headlines and drawing attention to the plight of Palestinians living in the occupied territories. On this 25th anniversary, the IMEU offers the following fact sheet on the First Intifada.

By The Institute for Middle East Understanding

Facts and figures

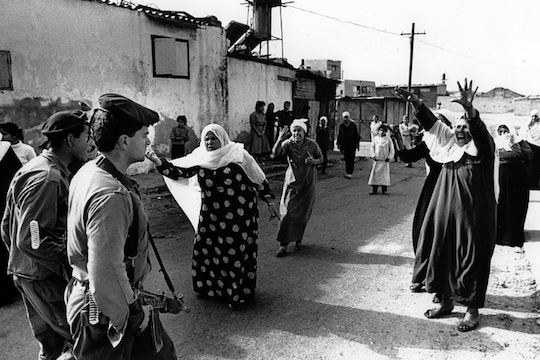

During the First Intifada, Palestinians employ tactics such as unarmed demonstrations, including rock throwing against soldiers, commercial strikes, a refusal to pay taxes to Israeli authorities, and other acts of civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance. They are coordinated largely by grassroots ad hoc committees of Palestinians in the occupied territories rather than the PLO leadership abroad.

In response, Israeli soldiers use brutal force to repress the mostly unarmed popular rebellion. Then Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin implements the infamous “broken bones” policy, ordering security forces to break the limbs [WARNING: Graphic video] of rock-throwing Palestinians and other demonstrators.

More than 1000 Palestinians are killed by Israeli forces during the First Intifada, including 237 children under the age of 17. Many tens of thousands more are injured.

According to an estimate by the Swedish branch of Save the Children, as many as 29,900 children require medical treatment for injuries caused by beatings from Israeli soldiers during the first two years of the Intifada alone. Nearly a third of them are aged ten or under. Save the Children also estimates that between 6500-8500 Palestinian minors are wounded by Israeli gunfire in the first two years of the Intifada.

In 2000 it is revealed that between 1988 and 1992 Israel’s internal security force, the Shin Bet, systematically tortures Palestinians using methods that go beyond what is allowable under government guidelines for “moderate physical pressure,” Israel’s official euphemism for torture. These methods include violent shaking, tying prisoners into painful positions for long periods, subjecting them to extreme heat and cold, and severe beatings, including kicking. At least 10 Palestinians die and hundreds of others are maimed as a result.

Approximately 120,000 Palestinians are imprisoned by Israel during the First Intifada.

In 1987, Hamas is founded in Gaza, formed from the Palestinian branch of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. During the 1980s, Israeli authorities encourage and tacitly support the Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas, viewing them as a counterweight to the secular nationalists of the PLO, part of a strategy of divide and conquer.

In 1992, in the face of protests from the international community, including the UN Security Council through Resolution 799, Israel deports more than 400 suspected members of Hamas and Islamic Jihad to southern Lebanon, including one of the founders of Hamas, Mahmoud Zahar, and Ismail Haniyeh, Hamas’ top leader in Gaza today. Refused entry by the Lebanese government, which doesn’t want to confer legitimacy on Israel’s illegal deportation of Palestinians, the exiles spend a harsh winter outside in a no-man’s land limbo. Many observers consider this a turning point for Hamas, whose members are given assistance to survive by the Lebanese paramilitary group Hezbollah. In addition to basic sustenance, Hezbollah gives the Palestinians advice and military training honed during a decade of struggle against Israel’s occupation of Lebanon that began following the bloody Israeli invasion of 1982. Hamas subsequently begins to use suicide bombers against Israeli targets, a tactic that was a signature of Hezbollah’s resistance to Israel’s occupation. Under pressure from the US, Israel agrees to let the exiled Palestinians return to the occupied territories in 1993.

The First Intifada gradually tapers off in the face of brutal Israeli repression and political co-optation by the PLO, ending by 1993.

Political repercussions: Madrid, Oslo and beyond

The outbreak of the First Intifada surprises nearly everyone, including Israeli military and intelligence officials, and the leadership of the PLO, which is then based in Tunisia after being forced out of its base in Lebanon in 1982 by Israel’s invasion.The First Intifada creates immense international sympathy for the Palestinian cause, and leads to international pressure on Israel to address Palestinian demands for freedom and self-determination.

While initially caught off guard, the PLO under Yasser Arafat attempts to harness the Intifada and exploit it politically. In 1988, the PLO recognizes the state of Israel. This is a major and historic compromise on the part of the Palestinians, who effectively renounce claim to 78 percent of historic Palestine. (See map here.)

Despite this compromise and pressure from the international community, the Israeli government of Yitzhak Shamir (1989-1992) refuses to acknowledge the PLO or to engage in peace talks with Palestinian representatives. Frustrated at Israel’s intransigence, US Secretary of State James Baker famously reads off the White House switchboard telephone number during congressional testimony, adding to Shamir, who isn’t present, “When you’re serious about peace, call us.”

The Madrid Conference

Following threats by the administration of George H.W. Bush to withhold $10 billion in loan guarantees unless Israel ends settlement construction, Israeli Prime Minister Shamir finally agrees to meet with Palestinian representatives – but not PLO officials, despite the fact that the PLO is considered the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people by the UN and international community. Talks between Palestinians based in the occupied territories, who are in close contact with PLO officials behind the scenes, begin in Madrid in 1991.

Soon afterwards, in an attempt to bypass the Palestinian representatives sent to Madrid, the Israeli government begins secret negotiations with the PLO, weakened politically since the disaster of Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon and Arafat’s support for Iraq during the first Gulf War, believing it will be more willing to compromise on issues such as settlement construction and fundamental Palestinian rights like the right of return for refugees expelled from their homes during Israel’s creation in 1947-9.

Oslo

In 1993, the PLO and the government of Israel under Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin (1993-1995) exchange official letters in which the Palestinians formally recognize “the right of the State of Israel to exist in peace and security. In return Israel only acknowledges the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. Pointedly, Israel does not recognize or accept the notion of an independent Palestinian state in the occupied territories.

The exchange of letters paves the way for the first of a series of agreements known as the Oslo Accords. In September 1993, Rabin and Arafat sign the Israel-PLO Declaration of Principles on the White House lawn. Oslo creates the Palestinian National Authority (PNA or PA), which is headed by Arafat.

Oslo is supposed to be an interim agreement leading to a final peace agreement within five years, however the Israeli government under Rabin (1992-1995) and subsequent prime ministers has no intention of allowing the creation of a genuinely sovereign Palestinian state in the occupied territories. Although Rabin publicly agrees to a settlement freeze, Israel continues to build Jewish-only settlements on occupied Palestinian land unabated. Israeli officials also refuse to agree to any provisions in Oslo that would explicitly call for an independent Palestinian state, going so far as to refuse to allow the title of President to be used for the leader of the Palestinian National Authority (in the years to come, this title slowly comes into common use by journalists and others, despite Israel’s opposition.)

During the Oslo years (1993-2000), Israel begins to impose more severe restrictions on Palestinian movement between Israel and the occupied territories, between the occupied West Bank and Gaza, and within the occupied territories themselves. This is part of a policy intended to separate Palestinians and Israelis, and to separate the West Bank from Gaza, which are supposed to be a single territorial unit under the terms of Oslo.

Israel also rapidly expands its settlement enterprise. Between 1993 and 2000, the number of Jewish settlers in the occupied West Bank (excluding East Jerusalem), nearly doubles, from 110,900 to 190,206 according to Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem. Accurate figures for settlements in occupied East Jerusalem, which are mostly built and expanded before 1993, are harder to find, but as of 2000 the number of settlers in East Jerusalem stands at more than 167,000 according to B’Tselem. (See here for Peace Now’s up-to-date interactive “Facts on the Ground” settlement map.)

Settlements, which are illegal under international law, are strategically placed in locations to divide the occupied territories into a number of cantons, with Palestinian population centers isolated from one another and from the outside world. The settlements are connected to one another and to Israel by a network of roads and highways, most of which only Israelis are allowed to use, forming part of what has been dubbed Israel’s “matrix of control” over the occupied territories. Today, nearly 20 years after the start of Oslo, there are more than half a million Israeli settlers living in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem.

In October 2000, Palestinian frustration at seven years of fruitless negotiations, during which time Israel further entrenches its occupation rather than rolling it back, boils over into a second, more violent uprising, sparked by a provocative visit by Israeli opposition leader Ariel Sharon, who is reviled by Palestinians for his brutal record as an officer in the Israeli military and as defense minister, to the Noble Sanctuary mosque complex in occupied East Jerusalem.

In July 2010, a video surfaces showing Benjamin Netanyahu speaking to a group of settlers in 2001, when he was in the opposition, bragging that he had sabotaged the Oslo peace process during his first term as prime minister (1996-1999), stating: “I de facto put an end to the Oslo accords,” adding that “America is a thing you can move very easily.” In the video, he also tells the settlers that the way to deal with Palestinians is to “beat them up, not once but repeatedly, beat them up so it hurts so badly, until it’s unbearable.”

The Institute for Middle East Understanding (IMEU) is an independent non-profit organization that provides journalists with quick access to information about Palestine and the Palestinians, as well as expert sources, both in the United States and in the Middle East. This fact sheet was originally published on the IMEU’s website. Read more about the IMEU here.