The inception of Fikra magazine, a Palestinian literary publication launched in July, was, according to its cofounders, driven by a vision that transcends geographical confines. As the digital realm becomes the norm for written media, Fikra (“idea” in Arabic) is intended to offer a unique platform to bridge the gap between the scattered Palestinian diaspora and segregated local Palestinian communities.

This undertaking is rooted in the Fikra team’s profound appreciation for literature, arts, and philosophy, and the belief that the power of the written word can reshape viewpoints, ignite conversations, and honor the richness of diverse Palestinian communities and their experiences. Fikra’s limited series of print copies also reflects the nostalgia of previous generations who grew up reading hard copies of newspapers and magazines, long before the internet existed.

Against the backdrop of a repressive reality, the concept of Fikra took shape as a project by and for Palestinians, prompted by the increased stifling of spaces for free expression among Palestinians inside Israel, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip — each facing their own distinct sets of challenges.

Cofounder Aisha Hamed is half Palestinian and half Dutch, and grew up between the Netherlands and the city of Nazareth, where her father is from. She and her partner, Kevin Kruiter, who also co-founded Fikra, decided a year ago to move to Ramallah to start their project.

“We were both diplomats [for the Dutch government] before, mainly in development cooperation and the Middle East region, for approximately five years,” said Hamed. “We were very much fed up with Dutch policies toward certain countries and groups within those countries. Palestine was a very difficult topic for me to handle, having both Dutch and Palestinian roots.”

Kruiter, who has a background in philosophy and literature, worked on global climate policy in the Middle East for five years at the Dutch Foreign Affairs Ministry in the Hague with Hamed. “It’s really frustrating to work in international affairs, especially in the West, because of quite stringent policies toward Palestine and the Middle East in general,” he said.

“It is becoming harder as governments are becoming more right-wing,” Kruiter added. “Although we tried quite adamantly to change the narrative within the ministry, after five years we were right where we started off, and there wasn’t that much change in the policy or narrative.”

The couple thus quit their jobs and moved to Palestine to start Fikra. They wanted to be based in Ramallah in order to be close to the writers and the team they work with, who cannot travel to Israel because of the occupation’s restrictions and the wider hardships imposed on Palestinians in the West Bank. Their location also feeds into the wider vision of a magazine run by and aimed at Palestinians, thereby “avoiding the Western gaze altogether, and not explaining [the basics] a lot,” Hamed said.

Hamed and Kruiter are striving to have an “open and uncensored” platform, opting to stick to independent funding and refusing any government or politically affiliated financing. “We wanted to be completely open and free to write what we wanted. If our writers wanted to write about the military resistance or about something that might be difficult for donors, then they don’t have to worry about that,” Kruiter explained.

What the founders did instead was to collect the magazine’s initial funding by launching a crowdfunding campaign at the beginning of this year, raising $30,000. They expect Fikra to become sustainable through subscriptions, with some articles available for free and the rest behind a paywall for $3 a month.

Fikra will mostly publish Palestinian writers and avoid non-Palestinian writing on Palestine, and they decided to have a website in Arabic, translated professionally into English. The founders describe it as a communal effort aimed at publishing diverse subjects. “We didn’t want to have any criteria in terms of themes or scope of the pieces, because we want our authors and artists to feel free to say what they want,” Kruiter said.

The founders also want Fikra to help facilitate the creative process for Palestinian authors instead of restricting it, with freedom to come up with new forms of literature and poetry.

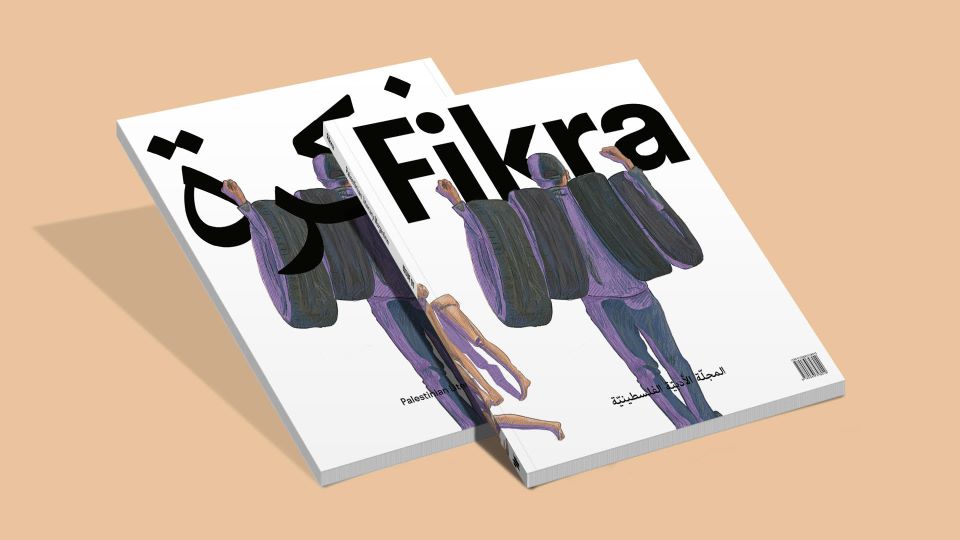

This also informed the idea of having a print edition: “We wanted to have something tangible as well because we publish not just literature, poetry, and essays, but also visual art,” said Kruiter. “Visual art is far more beautiful in print when done well.”

The magazine is also intended as a destination for established and up-and-coming writers alike: they are hoping to land prominent literary figures, but Hamed also stressed her personal appreciation for “working with new, talented, upcoming writers that people are not aware of yet. So what we try is to nurture those young voices that have each seen potential.”

Kruiter thinks Fikra’s lyrical nature will allow for an open imagination instead of hard facts about Palestine. “What I like most is pieces that indirectly delve into the emotions, the family relationships with this background of oppression and an apartheid regime,” he said.

‘A place we can call our own’

During the launch party, which was filled with performances by Palestinian artists, Hamed honored her father, Samir, who moved back with her to Palestine a year ago to start the magazine. “Without him, Fikra would not have been here,” she said, handing him a print copy of the publication.

“The Palestinian cause is reported on all the time through killings and bloodshed — bleak aspects that, with the rush of the news, [leaves] no space left for arts and literature,” said Palestinian journalist Faten Elwan during a speech at the event. “A magazine like Fikra is important because it will shed light on the bright side and give a different picture of us: we are people who love to live, and we have artists, singers, and painters who are looking for a chance to shine that is mostly overshadowed by breaking news.”

Elwan was emceeing the event with Jerusalemite activist Adnan Barq, who told the audience that Fikra is unique because “the whole world is being digitized and it is not so often that you find people returning to the original paper stuff. I’m very excited to see the print copy. It also has a vital and youthful frame that discusses issues in a different tune than we are used to in tackling political and social issues. I see a huge potential for it.”

Yasmine Omari, who works with Fikra, said she likes the idea of the magazine because as a Palestinian photographer, she lacks a natural platform. “[Fikra] will give me another avenue to publish my own and see others’ work,” she said. “Eventually, we will see critiques for art and photography, it will be a place that we can call our own. It will also help get our work out there in the world, especially to our international Palestinian community.”

Fikra’s first edition features a range of Palestinian writers and artists, some widely known and others less so. One entry is a fictional piece on human resistance; another is an interview with renowned film director Hany Abu-Assad; and another is a photo essay titled “Postage Stamps from Gaza.”

Mahmoud Shukair, a celebrated author from East Jerusalem who writes short stories and novels, wrote a fiction piece for Fikra titled “Letters to Shakira.” Characterized by dark humor and sarcasm, the story is about the international singer Shakira and how Israelis mispronounce the last name “Shukair.”

Shukair is enthusiastic about Fikra spreading Palestinian literature to a broader audience and noted that, in the absence of similar magazines since the closing down of poet Mahmoud Darwish’s al-Carmel magazine in 2006, Fikra has a void to fill.

The founders ultimately hope they are creating a space where Palestinian voices can thrive, unburdened by political constraints and embodying Fikra’s mission to transcend borders and bridge the Palestinian diaspora and local communities. Their aim is for the magazine to champion uncensored, independent content, emphasizing the importance of authentic storytelling, and offering a different perspective beyond the usual headlines of conflict.