Perhaps the greatest similarity between Abraham Lincoln and Yitzhak Rabin is that both men’s assassins succeeded in altering history. Following Lincoln’s death the reconstruction of the American south was abandoned and the Supreme Court accepted the notion of ‘separate yet equal.’ Following Rabin’s assassination, the occupation of the West Bank and the Palestinian people has deepened as Israeli settlements continue to grow.

By Ilan Manor

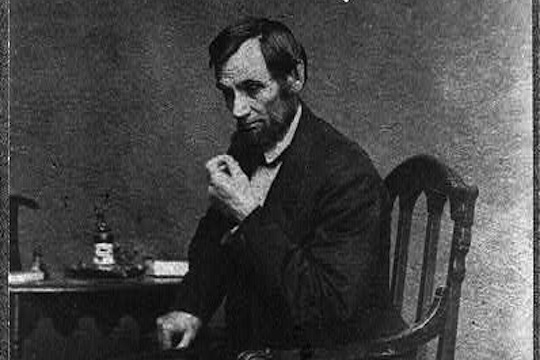

It was Ernst Lubitsch, an American filmmaker of Jewish decent, who used his 1942 classic comedy To Be or Not to Be to remark on the fate of dictators saying that “if they named a brandy after Napoleon and a herring after Bismarck, what’s Hitler going to be? A piece of cheese?” While dictators do often end up in one’s kitchen cabinet, great leaders share a different fate altogether being memorialized by great urban landmarks such as New York City’s Lincoln Tunnel or Rain Square in Tel Aviv. However, unlike the late Israeli prime minister, Abraham Lincoln has recently been revived by another American Jewish filmmaker, Steven Spielberg.

Nearly 70 years after Lubitsch’s masterpiece first opened, Spielberg has returned to the issue of the legacy of leaders in his film Lincoln. Interestingly, there is no other American filmmaker so engulfed in the task of shaping America’s collective memory as Steven Spielberg. In a series of productions, ranging from Saving Private Ryan to the mini-series Band of Brothers and The Pacific, Spielberg has defined what World War Two meant to America while adopting Ronald Reagan’s famous words “these are the men who took the cliffs. These are the champions who helped free a continent. These are the heroes who helped end a war.”

Now Spielberg has turned to defining what Lincoln meant to America, and perhaps to the world. While the film Lincoln focuses on a short period of two weeks leading to the passing of the 13th amendment to the Constitution and the abolishment of slavery, it aims to make a broader statement regarding the nature of Abraham Lincoln. Spielberg portrays Lincoln as a pure man, one who sees slavery as a stain on America worthy of a civil war. Yet Lincoln is also a pragmatic man, one willing to use the shortcomings of democracy in order to preserve and protect the American democracy. Fittingly, the film ends with the quote “the greatest measure of the nineteenth century was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America.”

As an Israeli who grew up in the United States, I couldn’t help but make an analogy between Spielberg’s Lincoln and the late Yitzhak Rabin. After all, both men came from humble beginnings, both rose to hold the highest office in the land, both dared to make history rather than succumb to its flow and both were murdered in an attempt to ensure that their vision would not become a reality. Much like Lincoln’s 13th amendment, Rabin’s 1993 Oslo peace accord was passed in the Israeli Knesset by a narrow majority of just two votes procured by political wheeling and dealing.

Perhaps the greatest similarity between the two leaders is that both men’s assassins succeeded in altering history. Following Lincoln’s death the reconstruction of the American south was abandoned and the Supreme Court accepted the notion of “separate yet equal,” a notion that would live on for a century. Following Rabin’s assassination, the occupation of the West Bank and the Palestinian people has deepened as Israeli settlements continue to grow. Much like the American Supreme Court, Israeli society has accepted a notion of “separate yet unequal” surrounding itself with concrete walls and settling under an Iron Dome of indifference.

Yet there is also a vast difference between Lincoln and Rabin. Most importantly, Lincoln’s vision of America would ultimately be realized. Beginning in the 1960s with the marches in Selma and Birmingham, and ending with the election of Barack Obama, America has nearly cured itself of the ills of slavery and segregation. In the American collective memory Lincoln lives on as the founding father of modern day America, the man who brought about the vision of the founding fathers of 1776.

With the swearing in of Benjamin Netanyahu’s third government, and the prominent role of the Jewish Home party in it, Rabin’s vision of peace with the Palestinians and the end of the Occupation seems to be fading away. In the Israeli collective memory Rabin remains a controversial figure; to some he symbolizes hope to others he remains a traitor. To some he is a courageous man, to others a naïve one.

Lastly, unlike Spielberg’s Lincoln, Rabin’s motivation for seeking peace with the Palestinians is still somewhat unknown. Was it a strategic decision? Was it because he feared Israel would lose the demographic war with the Palestinians? Was it because he had tired of war and bloodshed? Or was it, as in Lincoln’s case, because of a moral imperative? Because occupying another people is morally reprehensible and corrupting?

Whatever the reason, like his American counterpart, Rabin attempted to change Israel. One can only hope that both Israelis and Palestinians will not have to wait a century until his vision is also realized.

Ilan Manor is working on his MA in mass media at Tel Aviv University. He has previously contributed to The Jerusalem Post, +972 Magazine and The Jewish Daily Forward. His Hebrew-language blog has been featured several times in the Israeli press.