“Our Palestine Question: Israel and American Jewish Dissent 1948-1978,” Geoffrey Levin, Yale University Press, 2023

What is happening to the Zionist consensus? If you read much of the Jewish media, especially post-October 7, it appears to be alive and well, with most Jews understandably and passionately coalescing around the trauma induced by the Hamas-led attack. But something else seems to be afoot, especially in the shadow of Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza, which has taken over 28,000 lives and is showing no signs of letting up.

Among Israeli Jews, the feasibility of the war’s objectives are appearing increasingly uncertain, and an internal debate is percolating as to what the “day after” will look like. In the United States, the influence of progressive Jewish groups protesting the war and demanding a ceasefire has grown exponentially since the war began. These internal struggles around Israel’s future long pre-date October 7, and run much deeper than strategic questions about a single war.

In the world of letters, a plethora of books by Jewish authors have appeared in the last two years sharply criticizing Zionism itself, some even rejecting it.[1] The most recent example, which I review here, is Geoffrey Levin’s excellent new book “Our Palestine Question: Israel and American Jewish Dissent 1948-1978,” explaining how the Zionist consensus is not only being challenged today, but has been questioned in America for decades.

The relationship between memory and history — the former often taking the form of ritualization, the latter documentation — underlies conventional notions of how we view the past, implying that writing history primarily requires the act of remembering. What is often forgotten, though, is that forgetting is as important to history as remembering; it is the curation of a narrative, and narratives are, by definition, selective. We choose what to remember, sometimes how to remember, and thus we also decide what to forget, intentionally, as an act of erasure.

One is reminded of the importance and precarity of forgetting when reading Levin’s new book, as he examines what he calls “the hidden history of conflict between American Jewish liberalism and Israeli policy — one long lost in sweeping generalizations about relations between these two poles of post-Holocaust Jewish life.” I think Levin is being too kind: it is, in fact, the story of American Jewish dissent against Zionism, and later Israel, from the 1930s to the present.

Why, then, does he only cover 1948 to 1978? The establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 of course changed the nature of the debate, and in many cases quelled anti-Zionist sentiment among many American Jews after the fog of the Holocaust, the massive refugee crisis in Europe, and ultimately the emergence of the Jewish nation-state — but not completely. And 1978 was the first full year of the Likud party’s takeover after being elected the year before to replace what was, until then, a country run by the socialist-Zionist Labor government. Looking back, after many twists and turns, that year may be the germ-cell of where the country is today.

Forgotten figures, forgotten distinctions

The forgotten story resurrected by Levin is replete with many figures, once quite popular, today largely unknown: Don Peretz, William Zuckerman, Irving Engel, Fayez Sayegh, James Marshall, Morris Lazaron, Lessing Rosenwald, Sharon Rose, and Aviva Cantor. These are cutting room floor figures for most Jews today, even those who know a fair amount about American Judaism or Zionism. And in tracing these figures, Levin shows how, for years, one was able to be non-Zionist or anti-Zionist, or take part in anti-Zionist activities, without being deemed antisemitic.

Few people will know, for example, that Jacob Blaustein — who helped forge the alliance between American Zionists and David Ben Gurion at the Biltmore Conference in May 1942 — was not really a Zionist; if Blaustein is known at all today, it is as a kind of American Zionist hero of sorts. Blaustein remained close friends with figures like Elmer Berger, who together with Lessing Rosenwald, led the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism, which was against the existence of a Jewish state before and after its establishment.

Meanwhile, few will recall that most of the members of the 1970s Jewish protest movement Breira (Alternative), which was deeply critical of Israel and was shut down by a fierce negative campaign by the American Jewish establishment, were actually Zionists. Or that Fayez Sayegh, the most popular pro-Palestinian Arab spokesperson of his generation, was not considered antisemitic even by his Zionist detractors.

Perhaps the most central figure is Don Peretz and organizations such as the American Jewish Committee (AJC), the decidedly non-Zionist group (which Blaustein also headed) that was the most powerful U.S. Jewish organization in the postwar period. The AJC was non-Zionist in that it was not in principle against the Israeli state, even as it was harshly critical of the treatment of the Palestinian minority inside Israel; but the organization was opposed to Jewish nationalism being the raison d’etre of American Jews. In a certain sense, the AJC made an important distinction between the national identity of Jewish Israelis and nationalism (Zionism) as an identity for diaspora Jews — a distinction that has been forgotten.

Today, this distinction may sound dissonant because the Zionization of American Jewry and America more broadly intentionally collapsed any possibility of being non-Zionist and pro-Israel — that is, making Israeli identity and American Jewish identity categorically separate. Israel’s 2018 Jewish Nation-State Law codified this when it declared the State of Israel to be the “nation-state of the Jewish people,” assumingly whether they live there or not. Yet, ironically, this claim seems to undermine precisely what Ben Gurion wrote to Jacob Blaustein in an oft-cited letter from 1950, insisting that “Israel does not demand the loyalty of non-Israeli Jews.” Such a statement made by Israel’s first Prime Minister would likely be considered anti-Zionist today.

We don’t know all this, and much more, because many American Jewish historians don’t want us to. It upsets the narrative of the so-called “Zionist consensus,” a product of the 1970s projected backward to suggest all that precedes it is merely “antiquarian,” or intellectual refuse for a few scholars and archive rats with time on their hands. It shouldn’t interest us, they argue, because those debates have been decided. Levin deftly and with scholarly precision presses the “undelete” button and suddenly, as if in a hologram, a world largely forgotten pops back into focus.

The roots of a rebellion

Levin does not write “Our Palestine Question” as a partisan. It is the work of an adept historian, based on archival research and sound historical method, and its tenor is not ideological or histrionic. But that doesn’t mean it has no presentist concerns.

One way to frame the presentist agenda is by voicing two concerns many pro-Israelists often articulate: first, “Let us look forward and not back; why relitigate old debates when the problems we face are real and pressing?”; and second, “How can this younger generation of American Jews turn against Israel, and why do they rebel against the Zionist education we prepared for them?”

The first question can begin to be addressed by evoking William Faulkner’s famous quote, “The past isn’t dead, it isn’t even past,” or Benedetto Croce’s quip, “All history is contemporary history.” But how so? The claim to only want to look forward and not back is a sleight of hand, because it is premised on the lens of forgetting — a narrative curated for decades precisely to remember only part of the past and then claim it is comprehensive, or at least what is “useful.” But as Levin shows, once you open the historical archive, one often sees that what is inside is not that different from what one faces now.

The stock answer to the second question, that young American Jews are seduced by “woke” leftism, is convenient but unsatisfactory. While many of them may identify with the radical left, the fact is that they see a very different Israel than the one their parents fell in love with.

One of the salient points in Levin’s book is in showing how anti-Zionism between 1948 and 1978 was concerned with two distinct and only somewhat overlapping issues: first, the threat that Jewish nationalism posed to the Americanization, or assimilation, of Jews; and second, the way that Zionism as an ethnocentric illiberal project would not see to the just rights of the Arabs inside the state, from Ben Gurion’s refusal to allow Palestinian refugees to return in 1948 to the numerous land seizures facilitated by the 1950 Absentee Property Law and other methods.

For some non- and anti-Zionists, the liberal Judaism they espoused could not bear the weight of Jewish people’s shift from being a persecuted people to becoming a persecuting people. Zionists in Palestine such as Martin Buber acknowledged this, yet from their European experience and perspective, there was no alternative but to try and fight the tide of ethnonationalism. American Jews did have an alternative — America itself — and thus for many the fight was not against Zionism as much as for Judaism.

From rejecting Zionism to saving it

Here we see a crucial difference between Don Peretz and Elmer Berger. Peretz came from a strong Zionist background and was intimately engaged with the Yishuv — Palestine’s Jewish community — in the pre-state years. He saw firsthand the expulsion of Palestinians, the liquidation of their villages, and the state of the refugee camps, which he visited many times. He returned to the United States and wrote a dissertation in 1955, which he published as a book three years later: “Israel and the Palestine Arabs.” Whatever one makes of it, Peretz’s anti-Zionism was not a leftist call for universalism, it was the work of one deeply committed to Jewish responsibility and a Jewish future.

Similarly, Levin extensively examines the Yiddishist turned English publisher William Zuckerman, who founded the popular Jewish Newsletter in 1948. Not anti-Zionist per se, Zuckerman used his pen to castigate Israel’s moral failing in its treatment of the Palestinian minority. He described himself as “pro-Israel but anti-nationalist,” making another useful distinction that is now in the dustbin of history.

Throughout the early period of the state, there was a concerted effort on the part of the Israeli government to wage war against such critics, including trying to get Peretz fired from the AJC and Zuckerman fired from the London-based Jewish Chronicle. They were partially successful in the former (Peretz’s position was downgraded) and successful in the latter (Zuckerman was kicked out). This persecution was standard procedure with Israel intent on determining the tenor of American writings about the state’s affairs, curating a pro-Israel position long before the word “hasbara” came into play. The relationship between Israel and American Zionism was thus always hierarchical, policing voices that the former saw as threatening. But Peretz and Zuckerman were formidable foes and frustrated Israeli apologists for decades.

Berger was different. His anti-Zionism was an extension of the 1885 Pittsburgh Platform, Reform Judaism’s emblematic position that Jews were not a nation but carriers of a religious tradition. Berger did not focus much on the oppression of the Arab minority, although later in his career he moved in that direction; it is not that he didn’t care, but rather that his anti-Zionism was more about pro-Americanism for Jews. For this reason, Israel seemed to care less about him.

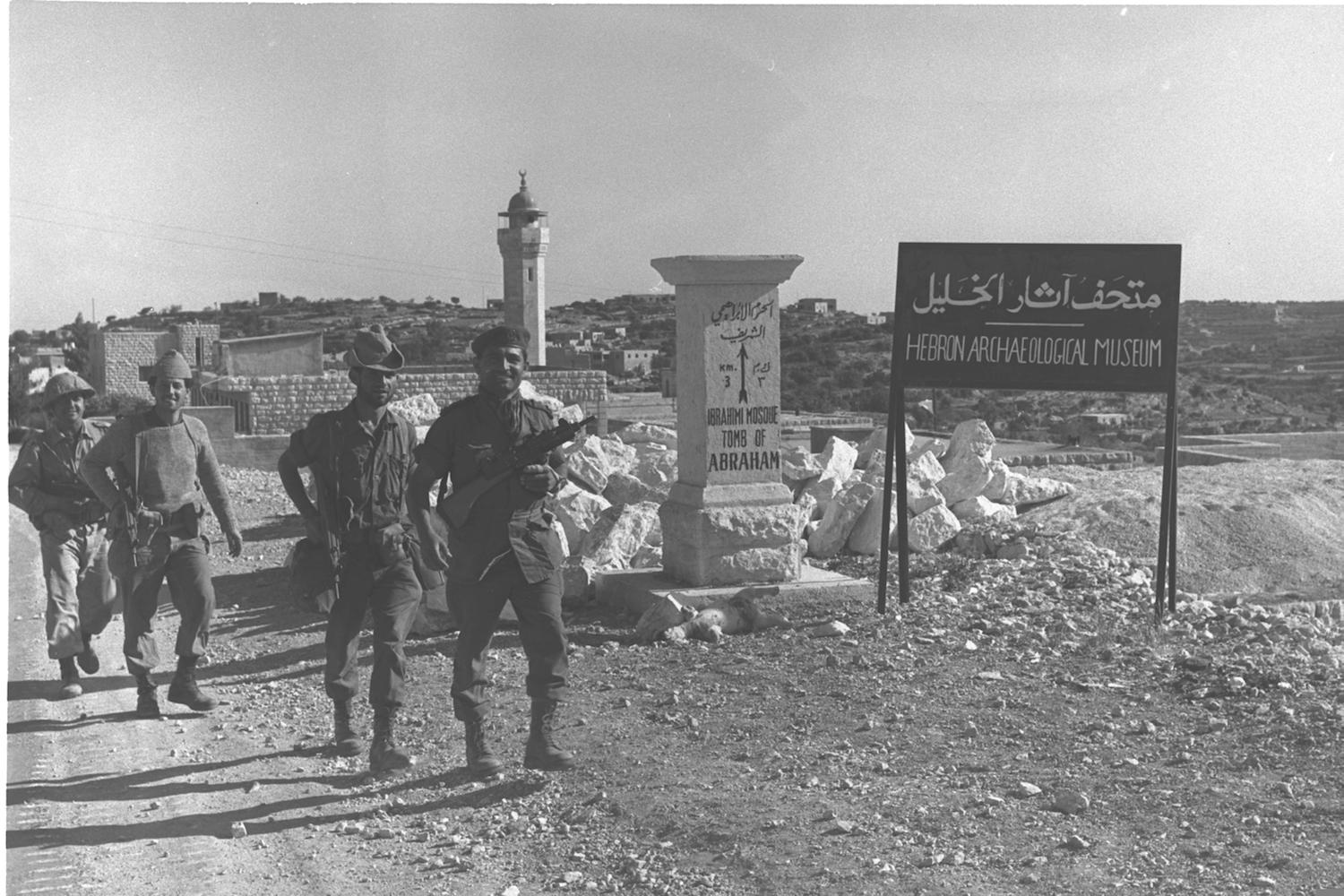

The final vestiges of the anti-Zionist front seemed to collapse after the 1967 Six-Day War, but not quite. While the victory might have put an end to the fear of a second Holocaust at the time, it was simultaneously the beginning of the military occupation, which in some way proved what Peretz, Zuckerman, and an aging generation feared: a more permanent instantiation of Jewish domination over the non-Jewish minority.

The response in Israel was swift. By the third week of June 1967, a leftist group known as Matzpen (The Compass) was already calling for an end to the occupation, which most Israelis at the time were calling liberation. The American Jewish response took a bit longer to congeal. As the settlement group Gush Emunim (the Bloc of the Faithful) took form in early 1974 following the Yom Kippur War, a group of young Jews in America, many from the New Left, and mostly Zionists, formed the Breira movement to oppose the entrenching occupation and fledgling settlement project. The same year, a young scholar named Noam Chomsky published his book “Peace in the Middle East,” which was met with harsh criticism from the mainstream. Most American Jews were unwilling to hear that the miraculous victory of June 1967 had a dark underside. That would change.

Levin’s chapter on Breira, which improves on previous studies thanks to more open access to its archives, documents how the movement sparked other similar youth movements nationwide focused on opposing Israel’s occupation. In some way, Breira is the real forerunner of contemporary progressive movements like IfNotNow, Jewish Voice for Peace, and others like them.

But there is an important distinction: almost all Breira members were Zionists. They were the children of the first wave of American Jewry’s Zionization, brought up on the vision of Israel as miraculously “making the desert bloom,” and all watched Otto Preminger’s film “Exodus.” Most were New Left liberals, many even radicals, but publications like the Jewish Liberation Journal led by Aviva Cantor was Zionist to its core. There were exceptions, such as Sharon Rose of the Jews for Urban Justice and the Brooklyn Bridge Coalition. But saving Zionism, not undermining it, was the raison d’etre of these groups. And yet, they were ravaged by the Jewish mainstream.

Restoring a Jewish ethos

Something has clearly changed in our time, and this is what raises the second question about why young American Jews today are questioning Zionism and even abandoning Israel. One possibility is that the New Left critics of Israel during the 1970s adopted the progressive ethos of Peretz, Zuckerman, et al and dropped the anti-Zionism. The present generation, in contrast, has adopted a New Leftism now refurbished as Critical Race Theory or anti-colonialism, and that has largely dropped the reflexive Zionism of those in Breira — in some way re-creating a wheel that was seemingly erased from history.

Why did this happen? Many younger millennials and Gen Zers were brought up with the previous generation’s romantic view of Zionism, but the post-2000 Israel they saw no longer cohered with that vision. For them, 1967 was not liberation but domination. Yet most had never heard of Don Peretz, William Zuckerman, or James Marshall — so where could they turn?

In this sense, “Our Palestine Question” can serve as a corrective. If a member of IfNotNow or JVP were to pick up Levin’s book, they might find much to relate to and learn from those he examines. The point is not to turn the newly non- or anti-Zionists into Zionists, nor is the point is to revive the non- or anti-Zionism of another era. Rather, the point is to inspire them to make their position more deeply rooted in a Jewish ethos informed by tradition and political theory from their community. Calls for “Decolonizing Palestine” and the radical progressivism of some of their peers are important, but there is a deeper, more Jewishly informed alternative to Zionism as it exists today that awaits re-examination, even if critically so.

Most read on +972

The time of Peretz, Zuckerman, and Blaustein was a time of Ben Gurion, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), and 1967. Ours is the time of Ben Gvir, Hamas, and October 7. For many young American Jews, liberal Zionism doesn’t work because they see a different Israel that is not going back to a place where perhaps it never was, even as we mourn the deaths of innocent Israelis, many of whom were peacemakers, and innocent Palestinians who are victims of the ongoing war in Gaza.

Yet the many titles published in the past two years, including Levin’s, should tell us something about the stability of the Zionist consensus, even in this time of darkness. To begin to think our way out of this, or perhaps more deeply into it, we need to look back at the cutting room floor of the American Jewish historian, or press the “undelete” button on our screens.

***

[1] Here are just a few of the titles: Omri Boehm’s “The Haifa Republic” (2021), Jonathan Graubert’s “Jewish Self-Determination Beyond Zionism” (2023), Daniel Boyarin’s “The No-State Solution” (2022), “Unacknowledged Kinships: Postcolonial Studies and the Historiography of Zionism,” Vogt, Penslar, Saposnik eds. (2023), Arieh Sapoznik’s “Zionism’s Redemptions” (2022); Amnon Raz-Krokotzkin’s “Mishna Consciousness Biblical Consciousness: Safed and Zionist Culture” (2023) [Hebrew]; Atalia Omer’s “Days of Awe: Reimagining Jewishness in Solidarity with Palestinians” (2019), Mikhael Manekin’s “The Dawn of Redemption: Ethics and Tradition in a Time of Power” (2023); my “The Necessity of Exile: Essays from a Distance” (2023); Marjorie Feld’s “The Threshold of Dissent: A History of Jewish American Critics of Zionism” (2024); and Oren Kroll-Zeldin’s “Unsettled: American Jews and the Movement for Justice in Palestine” (2024).