By upholding the state’s explicitly racist plan for Umm el-Hiran, the court shows again that it cares more about Israel’s Jewish character than about democracy and justice.

One year ago, the unrecognized Bedouin village of Alsira won a major victory when the Be’er Sheva District Court refused to reinstate demolition orders against the entire village. The case set a legal precedent for defending other unrecognized villages threatened by the discriminatory Prawer Plan, which could forcibly displace up to 70,000 Bedouin citizens of Israel living in the Naqab (Negev). That cautious hope was dashed last week, however, when, in a 2-1 ruling, Israel’s High Court of Justice refused to cancel eviction orders against Umm el-Hiran, home to 700 men, women and children of the al-Qi’an tribe.

Bringing an Arab land case to the Israeli courts is always a risky venture, but many believed that Umm el-Hiran, like Alsira, had a strong chance of success. Contrary to the state’s initial claims, the villagers are not trespassers on the land; the Israeli military government transferred them there in 1956, after it displaced them from their original home of Khirbet Zubaleh in 1948. This fact was confirmed by the High Court as well as the lower courts. In other words, there is nothing illegal about the villagers’ presence.

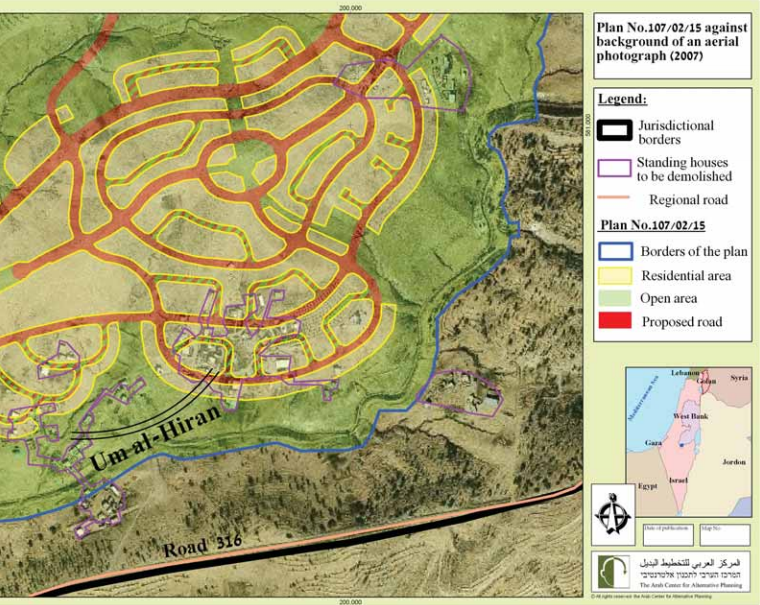

More importantly, the state’s plan for Umm el-Hiran is explicitly racist. It wants to demolish the village and relocate the Bedouin residents to the town of Hura – for the sole purpose of building a new Jewish town called ‘Hiran’ over its ruins. Umm el-Hiran’s adjacent sister village, Atir, will also be destroyed to expand the man-made forest of ‘Yatir.’ The Jewish residents who are slated to move into the new Hiran, who are tied to the West Bank settlement of Susya, are currently living in an encampment in the forest. And while the current residents of Umm el-Hiran have been denied water and electricity for decades, the future residents of Jewish Hiran have already been provided those services by the state and the Jewish National Fund (JNF).

In spite of these facts, the High Court still found a way to defend the state’s discriminatory plan. Justices Elyakim Rubinstein and Neal Hendel wrote in the ruling that the villagers’ appeal should have been taken to another body, such as a planning committee, because they saw it as dispute over new infrastructure. Even if the Bedouins’ rights were being harmed in some way, the justices continued, the state was providing sufficient alternatives to compensate for their relocation. These arguments, however, are absurd: the problem is not that new houses will be built, but that the current inhabitants are not allowed to live in them. Moreover, the state’s ‘alternatives’ force the families to accept far less land than they previously had, to abandon their rural way of life, and live in an impoverished township mired by social troubles and government neglect.

The dissenting opinion by Justice Daphne Barak-Erez acknowledged these problems, in part, when she wrote that the state’s decisions towards the Bedouin villagers contained “many flaws,” especially considering that they are not illegal squatters. She suggested instead that the state reassess the compensation it is offering them, including possibly allowing the Bedouin to live in the new town of Hiran. But like the other justices, Barak-Erez still avoided addressing the state’s discriminatory intentions.

The ruling is not just an affront to the al-Qi’an families, who are facing their third displacement in 67 years. If the High Court refuses to intervene in a stark, racist case like Umm el-Hiran, then it has effectively given the state a green light to pursue the same agenda against other unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Naqab, as well as unrecognized Arab communities throughout Israel. Successes like Alsira thus become the precarious exceptions.

Furthermore, the ruling has proven again that the High Court is more interested in protecting the policies and character of the “Jewish state” than the principles of democracy and justice. The fact that an Arab village inside Israel can be as easily targeted as one in the Occupied Territories, despite their citizenship, has reinforced the fear among many Arab citizens that attempting to advance their collective rights through the Israeli legal system is illusory. As such, Umm el-Hiran is yet another reminder that the Nakba of 1948, which will be commemorated on 15 May, continues to be a vicious reality in 2015.

Amjad Iraqi is a Projects & International Advocacy Coordinator at Adalah – The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel. Adalah has represented the village of Umm el-Hiran before the Israeli courts since 2002.