The following is an edited version of a talk on antisemitism delivered at the Italian Senate in Rome on January 12 at an event dedicated to the report by Francesca Albanese, the United Nations Special Rapporteur to Human Rights in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, which was submitted to the UN last September.

Anti-Judaism is ancient, while the term “antisemitism” is relatively new. It was coined in the last third of the 19th century and was first used to great political and cultural effect by the German radical writer and activist Wilhelm Marr in 1879. It signaled a turning point in the history of Jew-hatred, marking a division — though never firmed up, and always commingling and overlapping — between the classical, Christian hatred of Jews and modern, politically-rooted racist attitudes.

The term emerged and gained popularity as a reaction to the newly-won equality of Jews in Germany and other European countries. Antisemitism was a rallying cry against the rights of Jews, who were a defenseless minority, much as the movement against antisemitism was a movement for minority rights. With all the complexity of the term — as it manifested in politics, society, and culture — there was broad agreement among Jews and Jew-haters about its meaning: antisemitism meant the denial of Jews’ rights as a minority — whether their legal rights or even their right to live at all. There was, in other words, a consensus about what the term antisemitism meant — especially after the Holocaust.

How, then, has “antisemitism” evolved into such a contested term over the last generation, particularly among Jews? Indeed, there is perhaps no term whose definition so divides Jews these days. At the same time, among some European and American non-Jews there has emerged of late a reflexive reaction to denote as antisemitic any description that criticizes the policies of an Israeli government toward the Palestinians. The consensus about what the term antisemitism means has evaporated.

Antisemitism is real. It should be fought without reservation; this statement is self-evident. By “antisemitism,” I mean attacks on Jewish minority rights, and when the stereotypes used to attack Jewish minority rights are applied to Israel (for example, when Israel is portrayed as a historical devil or when Israeli Jews are essentialized, treated as having a character trait as inherent, or are portrayed with sweeping negative generalizations).

But the reason we talk about antisemitism to the extent that we do these days is not so much because cases of antisemitism have spiked — the evidence for this is complex, contradictory, and inconclusive — but because we deeply disagree on how to define it. And the reason for this state of affairs is that the issue of antisemitism itself has become inextricably entangled with the issue of Israel and Palestine. Our task is to find ways to distinguish between antisemitic speech and legitimate critique of Zionism and Israel, however harsh and painful it may be for some.

A complex history of antisemitism

Several decades after the Holocaust, and particularly since the 1980s and ’90s, countries in Europe along with the United States (and other countries as well) have taken very seriously the fight against antisemitism. Being accused of antisemitism is (for most people, I leave the antisemites themselves aside for now) a strong condemnation that reveals one’s indisputable moral and professional failure. That is how it should be.

But this condition has been misused of late as a weapon of personal destruction against critics of Zionism and of Israel’s policies toward the Palestinians. This weaponization of antisemitism is practiced against individuals, academics, journalists, professionals, and human rights organizations who dare to support equal national, political, legal, and civil rights for the Palestinians or to provide evidence-based reports about human rights violations in the occupied Palestinian territories. This has been the reaction, to name just two examples, to Amnesty International’s report “Israel’s Apartheid against Palestinians” published in February 2022; and to Francesca Albanese’s report to the United Nations in September 2022, as well as her activity in general as Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the occupied territories.

Accusations of antisemitism in this regard are part of a clear strategy: to get us bogged down in discussions about whether or not certain words and idioms are antisemitic — or were articulated with antisemitic intent — in order to avoid the fundamental discussion about what actually happens on the ground; that is, how Israel violently denies Palestinian rights. The aim of weaponizing antisemitism is distraction: to avoid speaking about how Palestinians live their life under occupation and instead to speak about Jewish victimhood.

It reminds me of what Toni Morrison said about racism: “[T]he function, the very serious function of racism … is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being … None of [this] is necessary. There will always be one more thing.” Accusing critics of Israel of being antisemites is such a distraction: it keeps serious people from doing their work to ensure equal rights to all the inhabitants who live between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, and instead keeps these people having to explain over and over again that they are not antisemites. There will always be one more accusation of antisemitism when evidence will be provided of Israel’s denial of Palestinian equal rights. Who, we might want to think, is interested in weaponizing antisemitism?

What emerges here is the complexity of the history of antisemitism since the term was originally invented to denote injury to Jewish minority rights. There exists, of course, antisemitic speech against Israel. But on another level, Jews in Israel are not a minority: they are the majority population in a state that structurally discriminates against Palestinian citizens of Israel, while keeping Palestinians in the occupied territories in bondage as a people without rights. We should fight to protect Jewish minorities outside of Israel, but we should not harness the fight against antisemitism in the interests of Israel’s occupying policies. The group without rights between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea are not the Jews, but the Palestinians, whose rights are denied by Jews.

Learning the wrong lessons from the Holocaust

I am a historian, and therefore bound to remind myself that things are more complex. In Rome [where this speech was originally delivered], in Via Portico d’Otavia, Via del Tempio, and their neighboring ghetto alleys, 75 years ago, on Oct. 16, 1943, Jews were rounded up by Germans in la razzia di Roma. On that day it rained in Rome. The Germans arrested 1,030 Jews, among them some 200 children under the age of ten, and sent them two days later from the Tiburtina railway station to Auschwitz. Fifteen survived the war; only one woman survived. Some Italians helped Jews; others helped the Germans.

Elsa Morante forever preserved these scenes in her masterpiece, “History. A Novel.” The protagonists, Ida and her son Useppe, arrive at the Tiburtina railway station on Oct. 18, 1943. The reader is led into the hellish scene via sensory perceptions. Ida hears an indistinct sound:

Toward the oblique road leading to the tracks, the sound’s volume increased. It was not, as Ida had already persuaded herself, the cry of animals packed into cattle cars […] It was a sound of voices, of a human voice […] At the end of the ramp. On a straight, dead track, a train was standing […] The voices came from inside it.

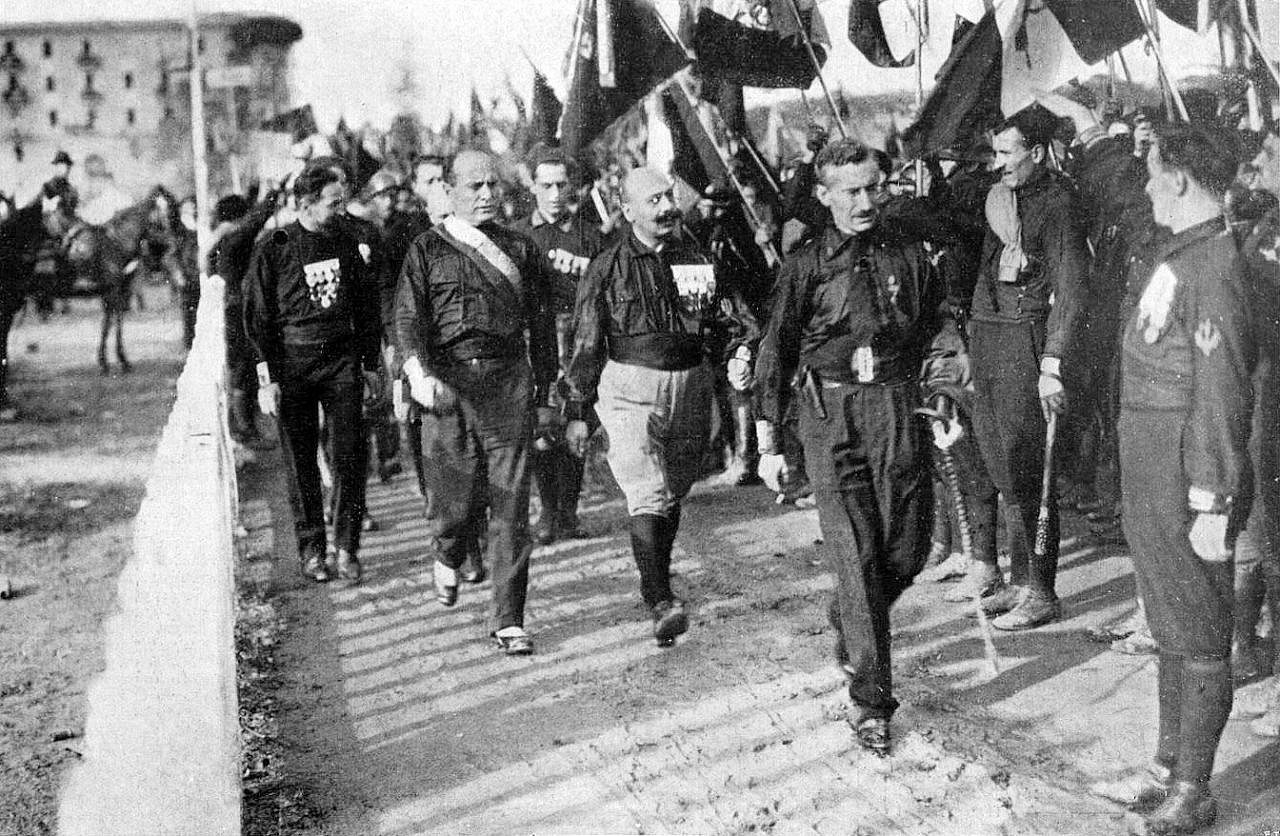

What are the lessons we can draw from the persecution of the Jews in Rome and during the Holocaust? I draw two lessons. The first is about the obligatory commitment of Italy, as well as other European countries, to remembering the Holocaust with a sense of historical responsibility and accountability; to fighting antisemitism with all its resources; and to support full rights — political and others — to Jews wherever they are. In Italy, it also means a conscientious coming to terms with the Fascist past in general, and with Fascism’s persecution of Italian Jews in particular.

The second lesson is that our challenge is how to juggle the tension between keeping the specific memory of the Holocaust alive and fighting antisemitism where it surfaces, while maintaining the universal value that emerged from the Holocaust: that equal rights and guarantees of life free from discrimination are fundamental to all human beings — rights that Israel denies to Palestinians today.

Accepting the accusation of antisemitism directed at people who provide evidence of the violations of Palestinian rights — calling it by its proper name, apartheid, and demanding accountability — is built on the axiom that one of the Holocaust’s lessons is that Israeli Jews are always right. Regarding any human group as being beyond moral reproach and historical accountability is a form of worship wise people should avoid. Learning from the Holocaust that all human beings deserve a life of dignity and rights, except those whose rights are denied by Israeli Jews, is a moral travesty. I am an Israeli Jew who lives in America. I am as wary of philosemites who think that Israel can do no wrong as I am of antisemites who think that Jews are eternally to be blamed. Beware of those who sanctify or dehumanize you.

I prefer Israeli Jews to be treated as human beings who, as all human beings, should be judged by and held accountable to their actions that inevitably comprise good and not-so-good deeds. Every society has moral ambiguities. Israeli Jews claim the memory of Holocaust victimhood, but they are also today wrongdoers with regard to the Palestinians. The status of victims and perpetrator can coexist in the same person, and the same group, in different historical times.

There is another way to connect the Holocaust to Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians, namely in the relationship to political power and its abuse. Jews were victims of the abuse of state power in Europe between 1919 and 1945; but they also abuse state power in Israel and the occupied territories today.

Of course, some critics of Israel might be antisemites; we should expose and fight them. But Amnesty International, Francesca Albanese, and countless others are not. Accepting and reiterating the accusation of antisemitism against defenders of Palestinian rights is blind to the fact that between the river and the sea there are two national groups of roughly 6.8 million Jews and 6.8 million Palestinians — one of which has all the rights that it denies, in various ways, to the other. This includes systemic racism toward Palestinian citizens of Israel, occupation in the West Bank, and siege on the Gaza Strip, creating what amounts to a huge prison.

In the name of democracy, Israel has maintained a political arrangement of violent suppression and occupation of millions of human beings for 55 years. Most people in the occupied territories do not know another reality, another way of life. There is no sign that Israel has any intention of bringing this occupation to an end — on the contrary, there are credible signs that it is permanent — and the occupied have no control over their occupiers or on public opinion. Israel speaks in the name of eternal victimhood and freedom for the Jewish people — a freedom that means, for Israel, the freedom to brutalize, plunder, and lay waste, to humiliate and degrade. The Palestinians are free to live as silent participants in their own demise. The main point is this: there is nothing antisemitic in documenting these conditions.

Hope against hope

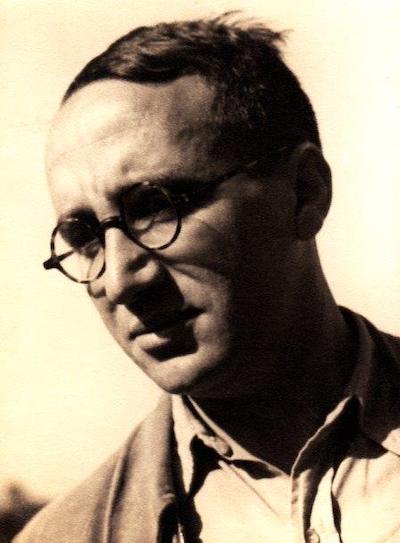

Rome and Italy are close to my heart and never far from my mind. My grandparents, Enzo and Ada Sereni, were born in Rome at the beginning of the last century. They emigrated in 1927 to Palestine, the first Italian Zionists to do so. They were 22 years of age. Enzo grew to become one of the young shining stars of the Labor Zionist movement. In 1943-44, the British Army and the leadership of the Zionist community in Palestine established a unit of parachutists of Jewish soldiers from Palestine whose mission was to drop behind enemy lines in Europe to help both the British forces and the Jews in Nazi-occupied territories. The mission was meant for young soldiers, but Enzo, then 39 years old with a family and three children, volunteered. Everyone — from Ada to David Ben Gurion, the leader of the Zionist movement in those years — opposed his decision. In May 1944 he parachuted near Florence, was caught by the Nazis, and murdered in Dachau concentration camp that November.

When Enzo arrived in Palestine, he realized there was another people already living there with very different political aspirations than his own. Enzo wrote a lot about Zionist and Italian history, and one thing he wrote in 1936 has always stayed with me. The progressive Zionist forces have only one way out of the current political impasse, he wrote — “the creation of a state power that will reconcile the interests of both nations and guarantee to each nation complete autonomy over its own internal policies.” And he ended with ringing words: Jews and Arabs should “develop a common fatherland and a common state.” It is not the particular political arrangement that is crucial here, but rather the vision of equality and humanity.

This today seems a fantasy. You need to be almost devoid of a sense of reality to believe that equal rights for all Israelis and Palestinians are a realizable political program. But I remember another sentence Enzo wrote, this time to his brother, Emilio, in 1927, during their correspondence on the meaning of history. Emilio was a Marxist, Enzo a Zionist. Emilio Sereni later became one of the leaders of the post-war Italian Communist Party. He wrote to Enzo about the inexorable road of history to Marxist utopia. Enzo replied with a splendid sentence: “Has history already been written and all that is left for us is only to perform it?”

We don’t know what the future will bring. We do know that values matter, words matter, the truth matters. Fighting antisemitism, as part of universal human rights and anti-racist principles, along with fighting for the full equal rights of all the inhabitants of the Holy Land and for an end to oppression and discrimination — this seems to be a worthy legacy and a worthy action plan for the present. Let’s hope, even against hope.