‘We are progress and modernization, freedom and equality, ‘peace and love.’ And they, what are they?’ On the history of the painful relationship between the Israeli Left and Mizrahim.

By Ron Cahlili (Translated from Hebrew by Orit Friedland)

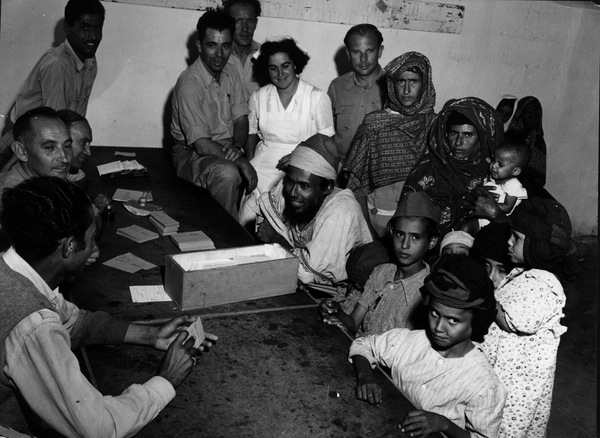

The common wisdom is that Mizrahim and the Left are like oil and water, and that the two shall never meet. This is odd, because a lot of the immigrants who came to Israel from Islamic countries in the 1950s, and from Iraq and Egypt in particular, were Communists. That is, lefties. Thanks to them, says Sami Michael [prominent Israeli writer of Iraqi descent] in the new documentary series On the Left, which I made for Channel 8, the Israeli Communist Party enjoyed around 20 percent support in some of the Ma’abarot (immigrant transit settlement camps), which is remarkable. When I ask Michael why, then, are they absent from the Communist Party ranks (Maki – Israeli Communist Party, at the time), he replies: “They [Maki] regarded us as primitives who must be taught and educated, because ‘what do they really know about communism?’ They called it ‘primitive Communism’, ‘the rags proletariat.’ This combination of Mizrahi and communist,” continues Michael, “let all the genies out of the bottle. From their point of view, this was the ultimate insolence, the absolute defilement. How can this monkey be talking about an ideology that developed in Europe? How dare he? This was ‘Salon Communism’.”

That may have been the origin of the rift. For the leaders of Israeli leftist movements, both Zionist and non-Zionist, including Ben-Gurion’s Mapai (Workers’ Party of the Land of Israel), Mapam (United Workers Party) and Maki, the Left, already – and justly – perceived as modern and revolutionary, was incompatible with Mizrahiness, which they saw as primitive and lagging behind. Let them learn to read and write, light the stove or use the toilet, it was argued, just as it is argued today against the Ethiopian community. Only then can they be allowed to touch the Holy of Holies: Engels and Marx and their teachings. Incidentally, there was no mention of nation-building or military power; their primary focus was on mending the economic situation. The issue of social justice, adds Michael, was non-existent in Maki at the time.

Maki, however, was not alone. Ever since, most of the Zionist leftist movements have regarded Mizrahim as unnecessary surplus, lacking the sophistication or modernity to accept the Left’s lofty ideas. What do we have in common with them, they wondered almost audibly, incessantly pushing Mizrahim into the welcoming arms of the Right and the ultra-Orthodox/Haredim who virtually embraced them with pathos and patronizing in the form of ‘operations,’ ‘programs,’ or ‘projects’ (as in Project Renewal for the rehabilitation of distressed neighborhoods, or the Liberalization Program, designed to “benefit the people,” i.e. Mizrahim, and so on). The Israeli Left kept saying, We are Europe, we are progress and modernization, freedom and equality and ‘Peace and the Love.’ And they, what are they? Human dust, always whining and complaining, excluding themselves from the collective “Working Israel”; “lacking a proper Zionist consciousness. It will take them years, if they ever manage it, to climb to the intoxicating heights of our enlightened socialistic consciousness.

But the Mizrahim failed to understand. They interpreted even the thickest spits as benign rain. The parents of Prosper Azran, former mayor of Kiryat Shmona, who were transported directly upon arrival in tarpaulin-covered trucks to the end of the world and dumped there, literally sinking up to their waists in mud, still believed “in God and Country.” What the state needed, we did, says Azran. The more it excluded us, the more desperate we were to be part of it. Significantly, during the 1950s and even the 1960s, he points out, many second-generation Mizrahim who were already born in Israel were named David (after Ben-Gurion) and Herzl (after Benjamin Zeev/Theodore). So eager were the new Mizrahim, who were not only driven out to the development towns and settlements in the remotest parts of the country and the desert but also turned into semi-Israelis or Israelis-on-condition, to belong, connect, feel part of. Most of them voted for Mapai, which they identified with the state itself. This was in addition to the wave of ‘Ashkenziation’ that had already started, and meant an escape from Mizrahiness at any cost – rewriting one’s biography, changing your name, working on your accent and hiding your culture.

Let there be no doubt about it. At the margins, in the dark storerooms of New Zionism, were nuclei of left-wing Mizrahim, who may not have been called leftist, but they behaved as such. Take, for instance, the Wadi Salib riots in 1959, when hundreds of Mizrahim – new immigrants from Morocco who were dumped in abandoned Palestinian homes in Haifa and left to cope with insufferable poverty and distress – rose up and demanded their rights in a series of loud protests that were brutally crushed by Ben-Gurion’s regime. Can this common, class-based, economic and ethnic revolt be labeled as anything other than leftist? Not to mention the sporadic Mizrahi riots which began in the Ma’abarot period (for instance, the Pardes Katz riots), or the short-lived political movements, Mizrahi by definition and composition, which attempted to gain seats in the Israeli parliament ever since the first elections and never even came close to the election threshold. In the first elections to the Constituent Assembly [later the Knesset], the Sephardim and Middle Eastern Congregations Party, led by Bechor Shalom Sheetrit, won four seats; the Yemenite Confederation led by Zachariah Gluska won one seat; all the rest did not cross the threshold.

In other words, there has always been a Mizrahi Left in the margins, but the partisan media (Davar, Al HaMishmar, LaMerchav, etc.) ignored its presence with callous bluntness, never associating it with the Left despite the fact that Left stands for, first and foremost, economic equality. In fact, except for Shalom Cohen’s monumental series in HaOlam HaZeh, ‘Screwing the Blacks’, in the early 1950s, and an extensive report on the Wadi Salib riots (1959), also in HaOlam HaZeh, there was virtually no expression of Mizrahim, let alone their economic, social or political aspirations, which otherwise were by any objective standards, leftist to the core.

All they ever wanted me to be was social, Mizrahi, common

In fact, up until the foundation of the Israeli Black Panthers, the first Mizrahi leftist movement, there was almost no Mizrahi political presence, unless in Mizrahi you read the ministers of police, welfare, and postal services. In the state’s early years, these positions were invariably occupied by ‘token,’ consciousness-lacking Sephardim, who were always obedient members of the ruling party, Mapai, such as Bechor Sheetrit, Moshe Hillel, Israel Yeshayahu, etc. Indeed, it was the Panthers, primarily comprised of distressed neighborhood activists, the second generation of the great wave of immigration, whose leaders were called Charlie, and Saadia, Abergel, and Kokhavi [all distinctly Mizrahi], who momentarily, shortly after its birth, distilled the Left’s ideas and in retrospect, became a real leftist movement. Key Panther activists first met activists from Matzpen [Compass], a radical anti-Zionist Marxist movement that had been in existence since 1962 and labeled “dangerous” from its inception. Its members include attorney Leah Tsemmel, Michel (Mikado) Warschawski, Moshe Makhover, Akiva Orr, Shimshon Vigoder and Haim Hanegbi, along with Rami Livneh, Udi Adiv and Ilan Halevi, who is currently the PLO’s representative in various European organizations. This dramatic and possibly momentous encounter may have involved shared joints and Jimmy Hendrix records, but it soon transcended into a discussion of ideology, vision and practice.

“Slowly and gradually,” Panther leader Charlie Biton recounts, “we began to hear some novel ideas from Matzpen members, not just about slums and economics and deprivation, but also about the settlements and borders and national priorities. I come from a Zionist home,” he says. “My father was a staunch Likudnik. These ideas seemed strange to me at first, but eventually I was convinced.” “I’ve been a Matzpen activist for years,” says Shimshon Vigoder. “I took part in hundreds of activities against the occupation and the settlements. But it was only when I became friends with the Panthers that I suddenly realized what it meant to be a Moroccan. What we experienced with Matzpen was nothing compared to the beatings and the violence we suffered there, and the kind of crazy persecution Matzpen was subject to is public knowledge.” I ask them why was the persecution so brutal? What made the authorities so scared? Biton is quick to answer: “It was this connection between Mizrahim and the Left. They realized that such a bond would be the downfall of Mapai’s rule.”

These leftist ideas, however, were not easily diffused among the Panther leadership. In fact, they divided and shattered the movement. Some of the splinter groups joined Mapai. Others focused on Histadrut (Workers’ Union) activity and the majority formed a common front with the Communist Rakah (New Communist List, the successor of the same party that had expelled the first Mizrahi leftist activists from its ranks). Biton, for instance, was a Rakah MK for four Knesset terms – until he sobered up. “The Israeli Left is hypocritical,” he asserts. “They only wanted us as vote contractors. Whenever I voiced a political opinion, Vilner and Toubi [Rakah’s veteran leaders] would hit the ceiling. All they ever wanted me to be was social, Mizrahi, lowbrow.” So, I tease Biton, were you Rakah’s David Levy [Likud’s token Mizrahi figure]? “Yes,” he says unabashedly. “I was Rakah’s David Levy. Nothing more, nothing less.”

The Left parties kept silent, ignored and gave up

And that is the second and critical problem. Israel’s leftist movements, both genuine and bogus, have always regarded Mizrahi activists as vote contractors, attractive bait for the ignorant masses rather than full and equal partners who could speak with the same passion about economic and employment reform and issues of peace and security. That was certainly the prevalent view in Mapai. And it was the same in the largely Kibbutznik and pseudo-left-wing Mapam. It was also true for the Communist Rakah, as well as for the New Left movements that emerged after the Big Bang of 1965 – HaOlam HaZeh – Koakh Khadash (lit. This World – New Power) led by Uri Avneri (editor of the radical HaOlam Hazeh magainze); Shulamit Aloni’s Ratz (Movement for Civil Rights and Peace), and later Sheli (Peace for Israel), Moked (Focus) and others. These left-wing movements were not only primarily Ashkenazi and bourgeois, they also focused on issues that were apparently very far from the Mizrahi public’s attention or consciousness – human rights, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, separation of religion and state, etc. Thus, while the majority of the Mizrahi public was struggling with economic distress and deprivation, social marginality, a nearly total exclusion from every sphere (politics, education, employment, culture, geography and more), most of the New Left movements were preoccupied with issues that the Mizrahi public regarded as either bourgeois or self-indulgent – or both.

Forty years later, Biton wonders, “How can I speak about peace and the conflict when my public is worried about its next meal?” Amir Peretz argues that the Zionist left-wing movements have not only turned the peace issue into a members-only club and closed it off to the masses, they also blatantly ignored the masses’ real plight, and then complained that they were right wing, primitive and lacking any socialist consciousness. Prosper Azran adds that “post-1967 left-wing movements were niche groups. They were concerned with one single subject, peace, in which I and others like me had no. In fact they only wanted me when they spoke about the minimum wage, social security, or development towns. But I,” he adds sarcastically, “was after comprehensive solutions, not just a quick fix to localized problems. I regarded myself as an intelligent person who was just as capable of speaking about matters of peace and security as about economics and bread and work.” Amir Peretz adds, “If you look at the attitudes of the Mizrahi public over the years, you’ll find that they have always been in favor of political solutions for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, quite moderate, despite the fiery rhetoric. But they could never find a political home in any of the left-wing movements.” In this respect, he says, it was the perfect tango: the more the left-wing movements – headed by Mapai – rejected the Mizrahim as nothing but subordinated voters, the more distanced the Mizrahi public grew from them, eventually shrinking their ranks to near extinction.

Another point worth mentioning here is the much-discussed emotional dimension. Immediately identifiable as Arabs – looking, speaking and behaving as Arabs in every respect and wishing to differentiate and distance themselves away from the dangerous and illegitimate Arab enemy – the Mizrahi public rushed into the welcoming arms of the Right and the ultra-Orthodox, who loathed, feared and persecuted the Arabs openly and unapologetically, unlike the Zionist Left, which was ostensibly pro-Arab. They seemed to be saying to themselves, “I don’t want to be or to look like an Arab, I want to be Israeli, as Israeli as it is possible to be, and to be Israeli means to be a (zealous) Zionist, Arab-hater, overtly patriotic and semi-racist.” And that is why, despite the fact that Arabness was an integral part of their genetic code, their public visibility eventually became distinctly and appallingly right wing, Arab-devouring and conservative.

And what did the left-wing parties do in response to these historical shifts which pushed the Mizrahi public into the darkest of corners? They kept silent, they turned a blind eye and they gave up the fight. Instead of storming the divided, fragmented, stigmatized and always apologetic Mizrahi public and turning it into a bridge for peace by myriad ways, the left-wing movements, both Zionist and anti-Zionist, political parties and non-parliamentary bodies (such as Peace Now, Yesh Gvul, etc.), became increasingly withdrawn and restrictive; and not only in terms of the range of subjects they addressed, but also in their ethnic composition (Ashkenazis and ‘Ashkenized’ Mizrahim) and their social milieu (bourgeois, urban, secular, educated).

The result? The acceleration of rampant capitalism (which began already during Mapai’s rule, despite the socialist pose adopted by Ben-Gurion and his cronies, not to mention the first government headed by the late Yitzhak Rabin, who embraced republican and capitalist values during his tenure as Israel’s ambassador in Washington DC, and promptly implemented them when he became the Israeli prime minister); the slowing down and eventual halting of the peace process, as well as catalyzing the Palestinian intifadas; a dramatic decline in the socio-economic-political status of Mizrahim (automatically associated with the Right, the Left felt less obliged to assume responsibility for their situation and fate, and felt particularly vindicated after the 1977 political sea change); the exacerbation of negative images of the Mizrahi public, who were no longer part of the ‘Right’ camp (certainly from the viewpoint of the leftist media), and so on. Succinctly, I say, good luck to us all.

Ron Cahlili is a filmmaker. His latest work, On the Left, a documentary series about the history of the Israeli Left, was recently broadcasted on HOT’s Channel 8, and is available for watching on VOD. This post was first published in Hebrew on Haokets.