The myth of the land of Mandate Palestine as an untapped oasis waiting for Jewish habitation is still thriving on both sides of the Green Line. Photographs are a key tool for perpetuating — and challenging — that myth.

David Rubinger, Israel’s most famous photographer, died on 1 March at the age of 92. His photograph of three Israeli paratroopers gazing at the Western Wall, taken minutes after Israeli forces seized Jerusalem’s Old City during the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, was widely revered as a symbol of Zionism’s triumphant destiny. Rubinger, however, was not particularly fond of the picture: “Part of the face is cut off on the right side,” he said, “in the middle the nose protrudes, and on the left there’s only half a face … photographically speaking, this isn’t a good photo.”

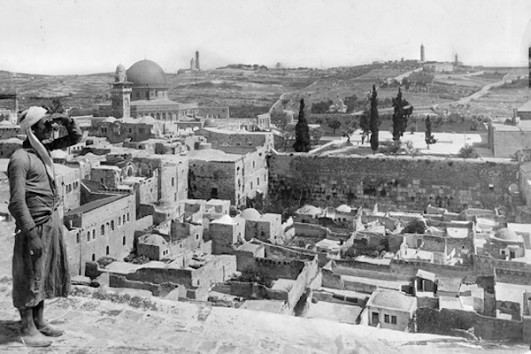

The soldiers’ faces were not the only things cut out of the shot. Behind Rubinger were the buildings of the Mughrabi Quarter of the Old City, home to about 650 Palestinians. Three days after the picture was taken, the Israeli army evicted the residents and demolished their houses and mosques. An open plaza now welcomes worshipers and visitors to the Western Wall, with no trace of the area’s former life. “There are those who write the pages of history,” President Rivlin said after Rubinger’s death, “and there are those who create them with their lens.”

Israeli visual history has always required the erasure of Palestinians. The National Library recently released forty aerial photos, taken by Zoltan Kluger in 1937, of what it described as “pre-state Israel” rather than Mandate Palestine. The images, which include views of the Nahalal moshav and Tel Aviv, bolster the Zionist myth of the land as an untapped oasis waiting for Jewish labor and habitation.

The myth is still thriving eighty years later, on both sides of the Green Line. Kluger’s photo of the fertile banks of the River Jordan could easily be used today to advertise the ongoing expansion of Israeli settlements and industries in the occupied Jordan Valley, which have displaced thousands of Palestinians. In the Negev, the Palestinian village of Umm al-Hiran is slated to be destroyed and a Jewish town built on its ruins. A video made by the incoming Jewish residents, who currently live in a temporary encampment in a nearby forest, shows two men searching the desert for signs of life but find “only sand and Bedouins” — Bedouins who are Israeli citizens.

The military occupation heralded by Rubinger’s photograph is now a permanent part of the Israeli state. Local maps and signs in Jerusalem either omit or redraw the Green Line; there’s little to tell pedestrians entering the Old City that they are crossing into occupied territory. The Trump administration has confirmed David Friedman, a supporter of the West Bank settlements, as its ambassador to Israel, and is touting a plan to move its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. A law passed by the Knesset last month officially recognizes dozens of settlement outposts built on private Palestinian property. A law passed last week denies entry to foreigners who call for any form of boycott against Israel or its settlements.

But images are not only a tool for the colonizer; they are a means of resistance for the colonized, too. In Walid Khalidi’s Before Their Diaspora, 474 photographs reconstruct the lost world of pre-1948 Palestine to debunk the myth of the region as “a land without a people.” Activestills’ photographers document scenes of Palestinian protesters kicking away American-made tear gas canisters and tearing down pieces of Israel’s separation wall. The residents of threatened Palestinian villages share live videos of house demolitions and military brutality on social media. Despite or because of Israel’s best efforts, Palestinians are still fighting back, lens for lens. Their struggle, Khalidi writes, “has little chance of fading into distant memory” while the “wounds of yesterday fester alongside those of today.”

A version of this piece was originally published in the London Review of Books blog, and is reprinted here with permission.