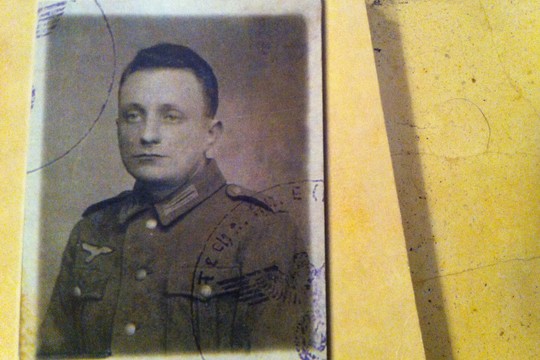

What if I told you that my late grandfather was a Jewish Soviet spy who infiltrated a Nazi army unit during World War II to support partisans, Jews and the Red Army? This is the true story of Jacob Ingerman, recently published as an e-book in English, titled, ‘A Jew in the ‘Service’ of the Reich.’

Trying to tell my grandfather’s war story is quite difficult, considering how completely imaginary and unbelievable it sounds. His is the story of a Jewish man who wore Nazi uniforms for three years while actually serving as a Soviet spy, marching through Ukraine, Poland, Germany and Italy with a German army unit and also forming underground cells and smuggling information and weapons to partisans, Jews and the Red Army from wherever he was, spending time with rough Gestapo agents and at the same time avoiding medical examinations so his Jewish identity wouldn’t be revealed, and still finding the time to develop love affairs with socialist activists throughout Europe. Seriously?

Well, it does sound absurd, at least if you never knew my grandfather.

I should state up front that I’m writing this post now because the Hebrew book written by my late grandfather, Jacob Ingerman, has finally been published as an e-book in English, which you can – and I think should – purchase here.

Jabob was born in Ukraine to a religious family and grew up to be a devoted communist and political activist in the USSR. After graduating with a degree in mathematics he went on to become a teacher in a remote village, and shortly after Germany attacked his country he joined the army and was wounded in combat.

Now, this is where things get really interesting. After going through special intelligence training, which included learning German, table manners and ballroom dancing, he was parachuted over enemy lines within Ukraine with a full cover story. It wasn’t even a week before he became friends with some German soldiers who told him about a tank division that was planning to pass over a nearby bridge that night. The intelligence was quickly transferred and that night the bridge – and quite a few German tanks – was bombarded and destroyed. The Nazi progress into the USSR was slightly delayed.

We notified the women prisoners’ leaders of the evolving plan and arranged with them to determine a list of the women to be freed… We agreed that their liberation would happen after I finished my nightly guard duty, so that I would not be suspected. According to the plan, I was to open all the locks during my shift and with the changing of the guard, the Underground people would steal into the compound and extricate the women. We coordinated all the details with the women’s leaders, mainly those who cleaned our offices and with whom I had ongoing contact [from A Jew in the “Service” of the Reich].

It wasn’t long before grandad (23 years old at the time) became the official translator for a German electric engineering unit, with which he was to spend the rest of the war. It was with this unit that he traveled from village to town, communicating messages to and from the local occupied population, while using these contacts to form resistance cells and create new ones, even within the German army itself. He continued with his underground work even when on loan as a translator for the Gestapo, a job that entailed participating in interrogations that included torture.

His number one task was to gather and transfer information, but he often did much more than that. He would steal weapons and give them to partisans in the woods or Jews terrorized by the Germans, help set captives free, foil his unit’s attempts to sabotage a power plant while retreating, and more. During this entire period he needed to not only conceal his underground activities and anti-fascist agenda, but also – first and foremost – hide the fact that he was Jewish, which turned out to be an excruciating task during shower times or when the whole unit was due for its monthly STD physical checkup.

Ideological and political humanism

I mentioned before how absurd and unbelievable my grandfather’s story may sound, and it does. But for anyone who knew him, or even read the book, it somehow all makes sense, for grandad was the nicest, friendliest, warmest and most likeable person one could imagine. He could become friends with more or less anyone within an instant of meeting them.

It was a sort of political humanism (or more precisely, mensch-ism) in action. He loved people from the bottom of his heart, which, alongside political theory, made him a communist, and vice versa – he practiced his communism by deeply loving mankind, and insisting on seeing the best in everyone, unlike the communist regime in which he grew up.

This was how he soon became friends with most of the soldiers in his unit. So quickly did he earn their trust that shortly after joining, on their first Christmas together, they each decided to give him part of the gifts they received from home (alcohol, sweets, coffee and the like), just to show how much they cared. His official commanding officer even decided to adopt him and set him up with a fine German bride!

All through his book grandad makes a point of separating the few ideologically motivated Nazis he met from the vast majority of the German soldiers, who were not party members, nor in any way interested in politics, essentially just ordinary men. He could never get along with the Nazis, but with the common people he didn’t have a problem.

On the designated night, I carried out my assignment and after the guard change I went to bed… but, of course I could not sleep. Before the operation, I’d been full of anxiety in case some unexpected fault was discovered. The German guards would carry out their watch in high boots which had a thick wooden sole, which inhibited their movement. Because of the extreme cold at night, they also wore long, heavy, fur coats. Since they could only move laboriously, the actual guarding was reduced to standing at the entrance. But the guards were armed and nervous… and it was hard to foresee what their reaction would be.

The two partisans who were responsible for carrying out the plan entered the camp during my watch, and hid. When I finished my shift, they waited a while to enable me to get clear and then jumped the guard, stuffed his mouth with a gag and covered his head with a sack. As planned, they didn’t kill him, just neutralized him [from A Jew in the “Service” of the Reich].

When the war ended the unit was in Italy, and fell captive to British and American troops. Against his original plans to return home, grandad found himself traveling here, where he joined the new Israeli state’s intelligence network, and won the Israel Defense Prize with his wife (my grandmother), Shula. But he remained a communist and a humanist until his last days, and was ever more frightened and upset by the direction the state was taking.

All throughout that terrible war, as if to make things harder for himself, grandad insisted on reading books by Heinrich Heine – the Jewish-German author whose books were piled up and burnt by the Nazis in cities across Germany. His daring to read forbidden literature shocked his fellow soldiers, and yet he somehow survived that too. When he passed, seven years ago, we chose a Heine quote to inscribe on his grave as a tribute. I miss him terribly.

A Jew in the “Service” of the Reich, by Jacob Ingerman, can be bought as an e-book on Amazon, and in Hebrew on Mendele. This post was also published in Hebrew on Local Call.

***

The end of the women prisoners’ story

They then extricated the women from the prison and opened the gate nearest the sea. At the time, cracks were beginning to appear in the ice and it was dangerous to walk on it. But the partisans knew all the risky sections very well and led the women on a sure path. Sleds were waiting to transfer them to the Russian side of the Azov Sea, some thirty meters from the compound.

The entire operation to release the women took no longer than half an hour. Only when the next guard came on duty, some two hours later, was his predecessor found wrapped in a sack and the compound broken into and open. He sounded the alarm, a panic started and we all hurried to the yard to see what had happened. We discovered footprints in the snow leading across the sea. Since the company numbered so few men, no attempt was made to follow the trail of the escapees. The Gestapo came to investigate the affair at dawn. They surveyed the area near the sea, but didn’t dare risk walking on the ice. They feared drowning, or being captured by the Soviet forces. One of the Gestapo concluded, “It’s not worth the risk for a bunch of Russian women.”

The affair succeeded beyond all measure. We managed to free about eighty women out of over two hundred. Several months after this action I received a medal. We thought about repeating the deed and releasing the rest of the women, but this never came to pass. The Red Army beat us to it and liberated Mariupol [from A Jew in the “Service” of the Reich].