From the moment it was established, Israel granted its Jewish citizens privileges at the expense of Palestinians. The ‘nation-state bill’ reveals the choice Israelis have to make about the future of their country.

Years ago, American journalist Ted Koppel hosted a fascinating televised debate between Rabbi Meir Kahane, the far-right anti-Arab leader, and Ehud Olmert, then a fresh-faced Knesset member from the Likud party. As the Israeli parliament is set to approve the Nation-State Law, which would enshrine discrimination against non-Jews in Israel, it is worth going back and paying close attention to the debate.

Kahane laid out his political vision without qualms. “Israelis, and especially those in power, are afraid that I will ask them the following question,” he says calmly. “Do the Arabs in Israel have the democratic right to sit quietly, democratically, and give birth to enough children to become the majority? They are afraid that I’ll ask the question. In Israel, currently, without Kahane in power, there is a law that allows Jews to receive citizenship from the mere fact that they ask for it, and that does not allow non-Jews to lease state land. Kahane did not legislate these laws. These are laws that were originally passed by the Labor Party.”

Olmert, an exceptional rhetorician, found himself stumbling to respond, retorting instead to an embarrassing discussion of chance and probability. And for good reason. Free of the shackles of political correctness and democratic veneers, Kahane was able to reveal the true face of Zionism in Israel: an inherent, perpetual demographic war against its Palestinian citizens. If Israel seeks to be Jewish and democratic, it needs to actively ensure a Jewish majority.

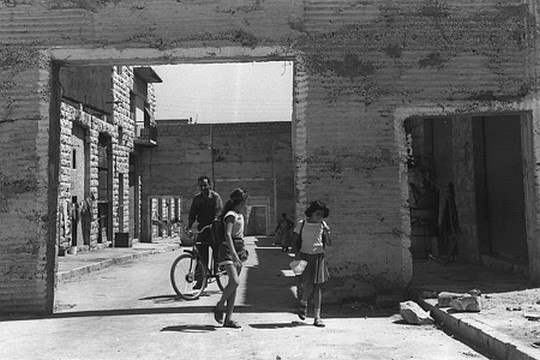

It is surprising therefore that it was the clause in the Nation-State Law that allows for the establishment of Jewish-only communities that has brought about so much opposition. After all, the Zionist project in Israel, since its inception, was one of re-engineering the land. This forms the basis for the state’s attitude and treatment of Palestinians — whether it is ethnic cleansing in the West Bank, forbidding family reunification, the Law of Return, or the fact that since Israel’s founding, not a new single Arab town has been established, save for some Bedouin townships in the south, built to stop the Bedouin population from expanding.

The Jewish public in Israel has learned to accept this deal, in which the civic character of the state are subjugated to its ethnic one. After all, that subjugation generally favors the Jewish population. The built-in privileges that Israel provides to its Jewish citizens — at the expense of its Palestinian citizens — are too numerous to count. But even if the inequality and injustice at the basis of this deal are not enough to cause Jews to seek out a different civil contract, we ought to pay attention to the fact that this re-engineering does not only affect its Arab citizens.

One can read the protocols of government meetings at the beginning of the 1950s, as the state prepared for waves of Jewish immigrants from Muslim countries. Those Jews were not part of the Zionist leadership’s demographic vision, and this in turn has informed the state’s attitude and treatment of Mizrahi Jews. This manifested in the begrudging way in which these immigrants were brought to Israel, as well as the way they were geographically spread out inside the country. The demographic vision was based not only on a country with as few Arabs as possible, but also one in which Mizrahim live on the margins, in the periphery, on its frontier. The state’s cruelty is the extension of that same exact worldview. In Israel’s demographic vision, there is no room for blacks — certainly those who are not Jewish.

This deal has forced Judaism itself to become the gatekeeper of the Jewish nation state. Because the Zionist state demands such a stringent filtration system, and because that role has been forced on Judaism, the latter must fulfill that role in the most conservative manner. While this might serve the needs of the state, it certainly goes against the needs of the many Jewish communities. This includes Ethiopians, immigrants from former Soviet states, ultra-Orthodox women, LGBTQs, non-Orthodox Jews, and others. This is the price that parts of the Jewish public pays for this miserable deal, which weakens our status as citizens for the sake of privileges based on our religious and national identity.

Over the years we learned to treat “Jewish and democratic” as axiomatic, to the point that undermining it is seen as an attempt to destroy the state. But there’s an alternative, and its name is a state of all its citizens. The Jewish public has hardly heard of it, since those gatekeepers make sure to silencer every real attempt to discuss the option. Recently, the Knesset chairman disqualified a discussion of a bill put forth by Balad MK Jamal Zahalka to recognize Israel as a state of all its citizens.

That’s how dangerous the idea of full equality and recognition of the national rights of both nations that live here really is. There was no fear that such a law would pass — the fear is of something entirely different: the possibility that the Jewish public will start to understand that the “Jewish and democratic” deal does not pay off, and that a country based on real equality and democracy is not only in the interest of the Arab public, but of the Jewish one as well.

All those who are horrified by the new nation-state bill should re-watch the Kahane-Olmert debate. Over the years, the reality in Israel has proven that Kahane’s understanding of Zionism was correct. After 70 years, the time has come to internalize the fact that we have a choice: between a Jewish and racist state, and an equal, democratic one. There is no third way.

This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.