The following is the introduction to ‘Awda: Imagined Testimonies from Possible Futures,’ a book of fictional short stories published in 2013 by Israeli NGO Zochrot and Pardes Publishing. The book is comprised of 12 vignettes written by prominent Palestinians and Jewish Israeli authors and thinkers about what life could look like after the return of Palestinian refugees to their homeland. Each story was published in both Arabic and Hebrew.

In his introduction, Zochrot’s Umar al-Ghubari tells the story of trying to convince every single person who worked on the book to travel together to Beirut for a special conference celebrating the anniversary of the book’s publication. The story has been translated and re-published here with permission.

***

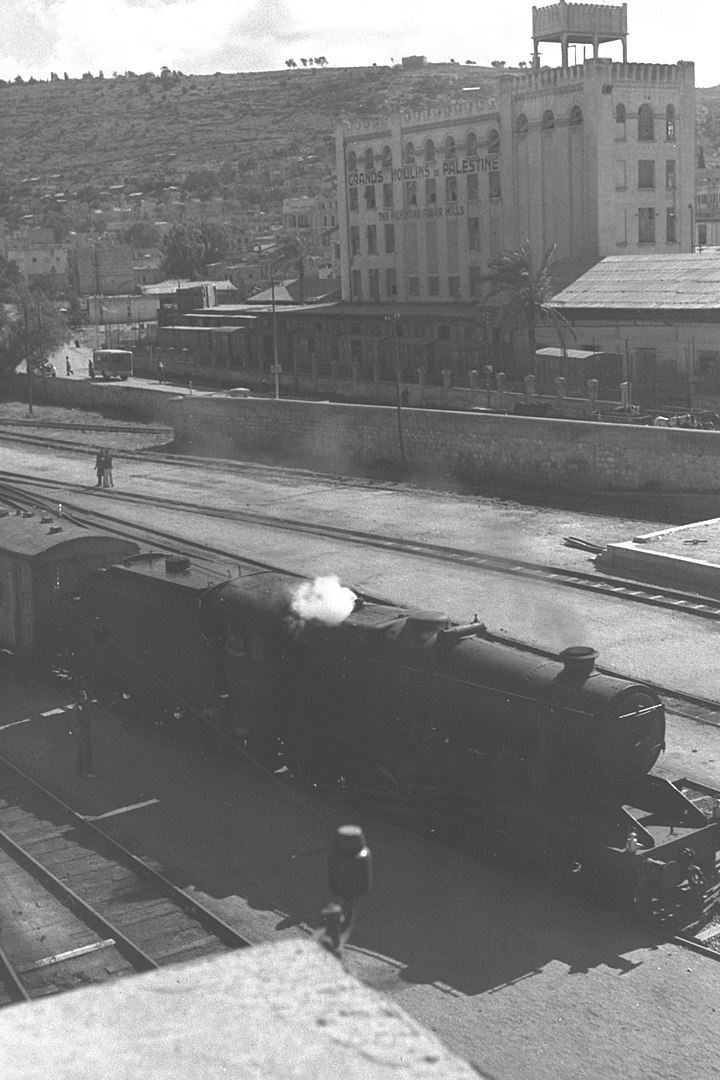

We all agreed to meet at 8 a.m. at the Haifa train station. All of us, meaning everyone who worked on, wrote, and helped create this book, “Awda” (Awda is the Arabic word for “return”). We were invited to take part in a conference titled “Successful Ventures from the Past,” and to speak about a book we wrote together years ago. We wondered why, so many years after the return, people were still asking us to talk about the crazy, seemingly impossible idea we put out to the world all those years ago.

“Why did you call today?” I asked the woman on the other end of the line. She sounded exhausted from talking and answering questions.

“Your book is still sparking interest here in Beirut,” she answered, “and you surely know that Lebanon has hosted a large number of Palestinian refugees since the Nakba and until the return. Many here are asking themselves how, back then, you came up with the idea of imaging a future that includes the return of Palestinian refugees. It was as if you predicted the future, despite what was happening in your country at the time and the imbalance of power, and saw that what seemed impossible was actually possible. We are interested in hearing about how the idea came about and what the responses to the book were at the time.”

“Wait, what is your name?”

“Noura.”

“Ms. Noura, I’m asking why you are calling today, Tuesday, when the conference is set to take place on Sunday. And you want to host everyone who took part in putting together the book? How will I gather everyone when I don’t know a large number of them personally, and haven’t been in touch with them for years? It seems even more impossible than the return of Palestinian refugees seemed back then.”

“We sent a letter a few weeks ago to your NGO, which if I remember correctly is called ‘Zchorot.’”

“Zochrot,” I corrected her.

“Yes, right. We sent it to your address in Tel Aviv, but the letter was returned to us after a few days with two comments: ‘This recipient could not be found’ and ‘Incorrect address.’”

I burst out laughing. Many things had changed after the return. Names, faces, attitudes. Jewish Israelis agreed to take down well-known Zionist symbols. “I think you must have sent the invitation to Yitzhak Sadeh Street,” I said. “Do you know who Yitzhak Sadeh was? He was the first commander of the Palmach. If only you knew what the Palmach did to this country and its residents. I won’t bother you with the details, but just know that the name of the street has changed to Samawal ibn Adiya. Do you know who Samawal was? An Arab-Jewish poet from Arabia. He was the one who in the 6th century wrote in a poem, which had nothing to do with Zionism, the following words:

“She disdained us for being so few / I said: the honorable are few.”

As for the name “Zochrot,” it means “remembering,” I continued. After the return, the name was changed and for several years became “Shavot,” meaning “returnees.”

Noura cut off my lecture and said: “It’s important that you all come. The conference will take place in a hall in the Ashrafieh neighborhood, next to the Sursock neighborhood.”

“Sursock?” I yelled, cutting her off. “The name Sursock is not especially popular in Palestine. Before the Nakba, when the Ottomans still ruled, one of the Sursocks bought land in Palestine and then sold it to the Zionist movement. On the other hand, the Bustros family, which also lives in Ashrafieh, are considered royalty in Jaffa. One of their sons built a hotel and a number of stores next to Jaffa’s clock tower, and until the occupation, there was a street named after the family. By the way, today the name of the street is once again Bustros Street, after the Israelis named it Raziel Street.

“In any case, send me the conference program and I’ll see what I can do,” I said.

“I just want you to know that it was the author Elias Khoury who suggested we invite you.”

“That is a huge honor. Will he be at the conference?”

“No.”

“That’s a shame. At the time I asked him to write a story for the book, but he politely rejected my request. I was hoping to ask him why. Okay, goodbye.”

***

“Hi Tomer, this is Umar,” I said over the phone. “How are you? How is your Arabic? Listen, do you remember the book we published years ago full of imagined testimonies from the period after the return?”

“You know me,” replied Tomer, “I can’t remember what I ate yesterday and you’re asking me about something that happened at least a decade ago? I remember the book but I no longer remember the details. What about it?”

“I got a call from the Madeena Society in Beirut. They invited us to a panel about the book on Sunday evening. We should prepare. Let’s meet on Sunday at 8 a.m. at the train station in Haifa.”

“No way!” Tomer said, switching to Hebrew as his anger grew. “To reach Haifa at 8 a.m., I need to take the 7 a.m. train from Jaffa. That means leaving the house at 6:30 a.m., which means waking up at 5:30 a.m. Never. I’m not awake during those hours. Let’s leave at noon.”

“Leaving at noon is a gamble. We’re cutting it close and the preparations will be complicated. We’re talking about the entire staff, around 20 people. If this panel is important to us, we need to prepare despite the lack of time.”

“Remind me, what’s the name of that street in Beirut? The one with all the bars and nightclubs? Will we visit it?”

“See you on Sunday morning.”

I called the rest of the staff members. Truthfully, we were never a staff, nor did we ever meet in person. The only place we met was in the book. In an imagined future.

The idea was the result of a limitless and wild imagination. We thought then that science fiction films appeared to be more like a hallucination, that the viewer grows resentful of their exaggerations and fabrications, eventually cursing Hollywood and its nonsense. Yet, these films can often serve as the source for new inventions, and as an engine for social and political change on the ground.

For example, one film from that period told the story of a black man who was elected president of the United States. In the eyes of new and old conservatives, the very notion was worse than sexual deviancy. For liberals new and old, it just seemed like a stupid idea. But that same idea, which so few believed in, became reality in 2008. It’s true that it hardly brought about any change, and it’s possible that the president’s heart is white, but he is still a black president.

So, we asked a few authors from that era to take a journey to the future. To write about what they see in Palestine after the refugees return to their homes.

I spoke to the Arab authors and Tomer spoke to the Jewish ones. We were worried and doubted that anything would come of our idea. When I told Palestinian author Muhammad Ali Taha about the idea, he responded, in a tone that walked the line between joking and scolding: “I am not a store, my dear. How can you ask me to write a ‘made to order’ story? I don’t think I can do it.”

I visited Muhammad not long ago in his new home in Mi’ar. We did not speak about the book, but we did discuss his return to the village, which was faster and easier than for other refugees. Until then, he had lived in the adjacent village of Kabul, and much of Mi’ar’s land was left untouched — as if waiting for the owners to come back and claim it. His beautiful home is perched on top of a hill, not far from Moshav Ya’ad. From there, one can see Carmel Mountain jutting out from the south and Ras al-Naqura to the north.

I visited him for one reason: I wanted to check whether he could hear the sound of the sea and the waves crashing into the grottos of Ras al-Naqura, just as he could during his childhood before the Nakba. He described that childhood memory to me when I interviewed him in February 2013. Perhaps I needed to see whether Mi’ar after return was the same as before the Nakba. What is certain is that the view is not the same.

Tomer and I spoke with a good number of writers. Some had rejected our request out of hand. They found it to be an impossible task. We asked the authors to extricate themselves from the situation they were living in at the time, and to look at reality through a different lens.

It was clear that it was not easy and we were conscious of the fact that many of us — those of us who lived in that era — were held hostage by a terrified and terrifying system that does not allow for movement beyond the walls it had built around itself. Walls of concrete and imagination. Others took on the challenge and tried their best, but weren’t able to bring the story to life. Return may have been over, but the story wasn’t.

I reached the Haifa train station before eight. I was stressed and excited for many reasons: Beirut, the panel, the event… I hoped that no one from our group would be late, because I didn’t have a backup plan. Would we leave the tardy behind, as I feared Liat Rosenberg, who headed Zochrot at the time, would demand, or would I succumb to my Arab compassion and suggest we wait for the next train departing two hours later?

Asad Odeh, punctual by his nature — and as pedantic when it comes to time as he is with the Arabic language — was the first to arrive. Tomer surprised me and arrived early along with Ami Asher. Hana Eidi informed me that he was in the United States and could not make it. Husam Othman made it by train from Ramallah. After him came Israa Kalash, whose husband drove her from Zir’in; only 20 minutes away, she said.

Upon arrival, Altayyeb Ghanayem said jokingly: “On this trip I will by no means be a translator.” Truth be told, in the days we put together the book, the work of translators was less profitable than ever, since fewer and fewer people needed translations. Aviv Gross, who designed the book, arrived holding her baby, deciding to bring him along to Beirut. Everyone was fussing over the baby while I glanced at my watch and prayed that everything would go as planned.

Just then Debby Farber arrived and offered her help. “I was the book’s editorial coordinator,” she said with a smile. “I missed this job. I’ll call the others to see where they are.” She would always call or send emails to see how far we had gotten in our writing, to push us to hurry up. I took my time, and every day she would ask me when I would be done with the introduction. Every time I thought of an idea and wrote it down, a different idea would come into my head and I would start anew. It took seven tries until I came up with a kind of introduction, a story of sorts.

Bruria Horvitz and Idan Barir, our two Hebrew translators, also made it. We laughed and asked them how the translation work was coming these days. They didn’t understand why we thought it was funny. Altayyeb approached them and the three went over to the side to talk among themselves.

Oh, now I remember. Yehouda Shenhav-Shahrabani told me ahead of time that he would arrive in Beirut from Baghdad, where he was visiting his cousins who had decided to move back to Iraq. It was almost 8:30 a.m. when Ala Hlehel parked his car and walked toward us, a cigarette in his mouth. After him came Zvi Ben-Dor Benite and Daniella Carmi. Adi Sorek arrived at 8:30 exactly; she ran to make it on time and wished us all a good morning.

Debby looked unsatisfied. She called Mati Shemoelof, who said that he had spent the night in Haifa and went to sleep late, but had ordered a cab and was on his way. Debby tried to call Amal Eqeiq but her phone was off. Mati and Amal arrived 15 minutes late, proving that I had been right to invite the group to the station an hour and a half before departure.

After everyone arrived, we sat at the café to rest until the train arrived. Only the train didn’t come, and the PA system didn’t announce any delays. When I asked the clerk at the ticket office, she told me it wasn’t her job and that I should speak to the people at the information booth. The clerk at the information booth said that I shouldn’t worry, that the train would certainly arrive soon and that it might be late by 10 or 15 minutes, that it’s normal. It was a very strange way to assuage my fears. I calmed myself down as I returned to the group, telling myself that there was nothing to worry about, that this is normal…

Just as the train finally arrived, my wife Samah called. She told me that one of our neighbors in al-Shajara, who arrived a year ago from Ein al-Hilweh refugee camp, claims the land on which we are building our new home does not belong to Samah’s grandfather, but rather to the family of famed Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali. I told her: “Samah, I’ll return from Beirut tonight and we’ll look into it tomorrow.”

“Of course,” she responded angrily. “Let’s see when ‘Mister Tomorrow’ arrives. I’m worried that…” the line grew fuzzy before cutting out completely. The train departed for Beirut.

We sat together in the same train car. It wasn’t crowded and the passengers varied in their appearance. There were brown-skinned and blonde people, locals and tourists. Who would have thought that the ride from Cairo to Jerusalem to Baghdad through Damascus could be so comfortable — with no borders, checkpoints, or fences?

“We’ll arrive in Beirut in an hour,” I told them. “Noura will greet us. We’ll rest at the hostel, eat lunch, and then sit to prepare the panel and discuss a number of issues, such as who will speak, what we can expect of the panel, who will be in the audience, etc.” Mati said he wants to speak on the panel. “Wait, Mati” I told him, “let’s see what the others think.”

We didn’t reach a full consensus. I suggested we delay the issue until we reach Beirut where we would be able to confer with Yehouda Shenhav-Shahrabani, our elder statesman. There is no doubt that his opinion is of utmost importance, and anyway it would be unjust to come to a decision without him. I suggested we try to imagine the kinds of questions we’ll receive from the audience.

I guessed, and hoped, that the audience would ask me about the title of the book, “Awda: Imagined Testimonies from Possible Futures.” Ten years ago, while we were discussing the title, Hebrew was still the dominant language in the country. Back then, I suggested that we refrain from choosing both a Hebrew and Arabic name, since there is a likelihood that the Arabic name will disappear, and everyone will only use the Hebrew one.

It reminded me of the Arab-Jewish village near Latrun, where I lived for many years. They decided to give the village a Hebrew name translated into Arabic on the assumption that the official name will be made up of both names conjoined by a hyphen. We decided to put the Arabic name first and call the village “Wahat al-Salam-Neve Shalom” (Oasis of Peace). And yet, most people still referred to the place as Neve Shalom only, hardly ever mentioning the village’s Arabic name. That’s generally how it went with institutions named in both languages; Hebrew always took precedence. I suggested to Tomer, Liat, and Debby that we don’t make the same mistake again with the book.

“And today?” someone in the audience might ask. No one could answer.

The atmosphere on the train was pleasant. The authors and the translators exchanged jokes. All of Mati’s jokes were below the belt and had to do with sex, and he did not shy away from using the kind of dirty language he uses in his books. Embarrassed and shifting uncomfortably in my seat, I finally told him: “Perhaps… maybe it is not appropriate for us to speak like that here.” To save both of us from the embarrassment, I told him to expect a similar question from the audience and that he should prepare a compelling answer. After that we were silent.

Israa turned to Ala and said: “Remember how hard it was for you to imagine a situation in which all the refugees returned, and you brought back only 200,000, and that your hands were tied by the regime you had gotten so used to, and that you left the symbol of the menorah on the passport?” Ala nodded his head in acknowledgement, before turning the tables back on her: “And you, isn’t it true that you made Jewish Israelis disappear as if they don’t exist, and you didn’t dare imagine life in Zir’in or in Palestine with them?”

The train stopped at the al-Bassa station, just before Ras al-Naqura. I told Tomer: “Al-Bassa was rebuilt, and my friend Wakim Wakim was elected to head its council. I heard that a well-known Jewish family in Shlomi, which was built on al-Bassa’s land, wanted to leave the area out of fear of revenge after residents of the village returned to their homes. You know why? This family turned al-Bassa’s mosque into a cowshed, defiled the church, and refused to allow Wakim and the few residents who remained in the country and lived in Mi’ilya to repair it. Wakim convinced the family to stay and denied any intention of revenge. Perhaps we should visit al-Bassa one day. I would like to see whether they rehabilitated the Al-Musheirifa tourist area and rebuilt the park that was there before 1948.”

Slowly, the train car grew quiet. Conversations dwindled down to small groups or couples, while others, including myself, simply kept to themselves in order to rest in the time left before we arrived in Beirut.