On the weekend of Sept. 17-18, while most of the United Kingdom was distracted by the impending funeral of Queen Elizabeth II, tensions between Hindus and Muslims in an English city boiled over into violence. In Leicester, which is home to some of the country’s largest Muslim and Hindu populations, Hindu men — some of whom had traveled from other parts of the U.K. — marched through Muslim areas of the city. They chanted “Jai Shri Ram,” a Hindi phrase meaning “Hail Lord Ram” that has been co-opted by Hindu nationalists and has anti-Muslim undertones. Windows were smashed, bottles were thrown, and fights broke out. A flag from a Hindu temple was snatched and burned. The High Commission of India in London released a statement condemning the violence and the “vandalization of premises and symbols of Hindu religion.”

Observers of political currents in India itself have become accustomed to seeing this kind of street violence; attacks against Muslim communities by Hindu nationalists are now commonplace, while the Indian government is regularly demolishing the homes of Muslim citizens, banning Muslim girls from wearing the hijab to school, and preventing Muslims from praying at historic mosques. Parallels with Palestine-Israel — from the annual Flag March on Jerusalem Day to settler raids on Palestinian villages in the occupied West Bank, in step with escalating state-level repression — are impossible to avoid, raising questions as to what we might learn by considering the rise of an emboldened Hindu nationalism alongside the mainstreaming of Kahanism in Israel and diaspora Jewish communities.

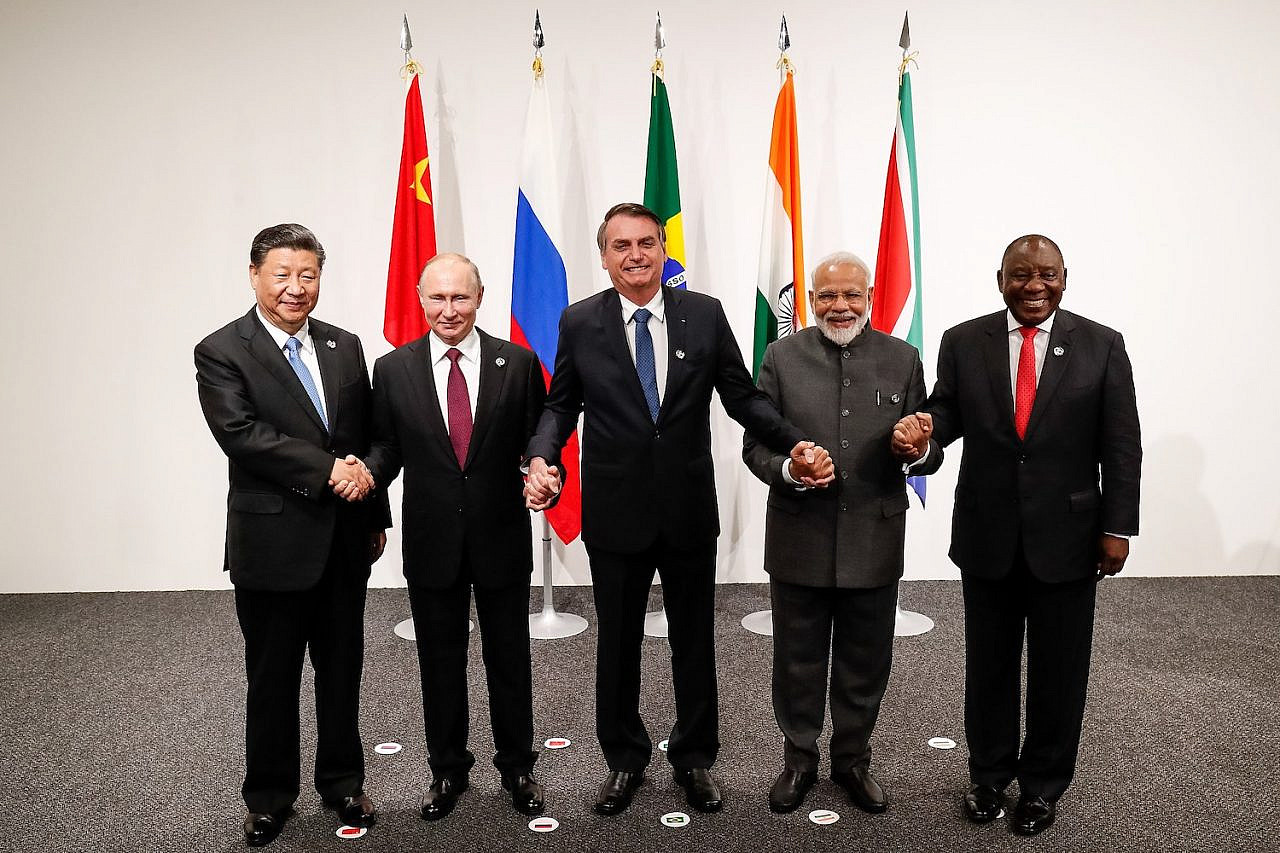

In recent years, Israel and India have cultivated a very public strategic alliance, born from the political ambitions of both Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and newly re-elected Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Against the backdrop of flourishing far-right nationalism and authoritarianism, the governments of both countries have also increasingly cracked down on civil society, harshened measures in occupied and disputed territory, and stepped up Islamophobic rhetoric and policies.

Azad Essa, a New York-based journalist and the author of “Hostile Homelands: The New Alliance Between India and Israel,” argues that “At the heart of this new alliance is Islamophobia, and [the fact] that both Zionism and Hindutva are pushing colonial and expansionist ideas. Both are ethnonationalist ideologies with an emphasis on race, territory, and nativism.” To understand more about the political, economic, and cultural ramifications of India and Israel’s ties, +972 Magazine spoke with Essa about the relationship between Hindutva and Zionism, and the growing extremism in the Indian and Jewish diasporas.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

In September, we saw a major escalation in street violence in the U.K. between Hindu and Muslim communities with roots in the Indian subcontinent. Why is this escalating now?

That is the question we are all asking ourselves, and there is no simple answer. But something has changed in the past few years. Under Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India has become very close to a Hindu state, or a Hindu Rastra. This has has given the impetus to those in the diaspora to express the Hindu nationalist or Hindu supremacist ideas more openly. It’s always been there under the surface, but [Indians] in the Hindu diaspora [now] feel emboldened — and not just in the U.K.

In mid-August the Indian Business Association in Edison, New Jersey, organized an India Day parade, which it has done for close to two decades. They did two very egregious things during the rally. First, they brought Sambit Patra, the national spokesperson from Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), who has been very Islamophobic in the past, to be the key guest at the rally. Second, they brought a bulldozer, covered it with posters of Modi and Yogi Adityanath [the chief minister of the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh], who is known as “Baba [Daddy] Bulldozer,” and paraded it through the streets of Woodbridge and Edison. The bulldozer is now an anti-Muslim symbol in India, because if a Muslim speaks out against the Modi regime, there is a good chance their house will be demolished under the [pretext] of “development” and “fixing corrupt housing practices.”

Another factor is the geopolitical shift that has taken place with regard to China. The United States in particular sees India as its ally in the coming war with China. This means India has been able to escape scrutiny even as its democracy slides and attacks on Muslims, Dalits, Christians and thereupon journalists, activists, and artists become rampant.

With the [New] Cold War with China, a lot of jobs are also moving to India, and the Indian IT sector is fundamental to Silicon Valley. So although European and American civil society are becoming increasingly concerned with what is happening in India, there is no political will to confront Modi.

In July, for example, U.S. lawmakers voted for an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) which would protect India from being slapped with sanctions because of its continued defense trade partnership with Russia. It was introduced by an Indian-American lawmaker, Ro Khanna, who is supposedly a progressive — he’s against the war in Yemen and has spoken up about Saudi Arabia and arms purchases. But he is the one who proposed the deepening of defense ties [with India] and called for an India-specific waiver.

What are the origins of Hindutva ideology?

The first half of the 20th century saw a lot of independence struggles come to the fore, including in India. Hindutva activists were influenced by several European thinkers, like William Jones and Max Mueller, who saw India as the cradle of civilization. This urged early proponents of Hindutva to call for a return to a pure India, in which Hinduism was the basis of the society. As a result, Hindu nationalists argued that Hindus were the original inhabitants and that everyone else were foreigners or invaders who had contaminated the nation.

As the struggle for independence from the British started, the Hindu nationalist movement looked at Muslims as their main [internal] enemy that needed to be disciplined. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) organization was established in 1925 and became the central hub for Hindu nationalist supremacist ideology [with the aim of] creating the Hindu state. The RSS gave birth to a youth wing and a religious wing, and created charitable organizations, an educational syllabus, and would later build a political wing — the BJP.

The RSS and Hindu nationalists also looked to fascist regimes in Europe such as Mussolini’s Italy for inspiration. RSS members went to Italy in the 1930s and 1940s and came back to India and built schools for young people; right-wing Hindu journalists reported on fascism in Europe as [a desirable means of] disciplining society; and even the way the RSS dress, with short brown pants and long socks, is borrowed [from 1930s Europe].

Following the pattern of Indian emigration during the 20th century, the RSS formed international wings — the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (the HSS) — first in Kenya, then in the United Kingdom and the United States. It is also important to note that most of the Indians who migrated during this period were upper caste Hindus — it was they who pioneered this movement from the outside.

How did the India-Israel relationship develop?

From the very start, it was a reluctant relationship — especially from the Indian side, with the leadership of the [Indian National] Congress sympathetic to Palestinians. Prior to the partition of the Indian subcontinent [in 1947], these sentiments were originally shaped by impulses of Mahatma Gandhi and Nehru who saw European Jewish migration to Palestine as a provocation, and as an act of colonialism. The support for Palestine then became strategic. India had major energy interests in the Arab world, and also relied on those states to take its side in the conflict with Pakistan over Kashmir.

India liked to project itself as the vanguard of the developing world. [But after the Israeli occupation began in 1967,] Palestine was receiving a lot of attention from the international left, and India wanted the Arab world to ignore its own colonization of Kashmir. The fact that Pakistan was propped up by the United States pushed the issue of Kashmir to the side for some time, because India was [seen as an anti-imperial power].

Meanwhile, India was already establishing covert ties with Israel. In 1962, when India went to war with China, it secretly called on Israel for help, and [did so] again in the wars against Pakistan in 1965 and 1971. In the late 1960s, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi established RAW, India’s equivalent of the Mossad, and authorized the two organizations to begin cooperating.

By the 1980s, India wanted to get closer to the United States — mostly for economic reasons. India’s population was growing rapidly and the state’s new leader, Rajiv Gandhi, wanted India to be part of the global economy, which meant deregulating aspects of the economy that were seen as holding them back. With the end of the Cold War in sight, he also wanted to reduce India’s military dependence on the Soviet Union, and to boost the country’s stature by becoming more affluent and more influential on the global stage.

In 1988, Gandhi traveled to New York to meet with American lawmakers. One of them, Congressman Stephen Solarz, organized meetings for him with the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) and the American Jewish Committee (AJC); they made it clear to him that if he wanted to strengthen ties with the United States, that meant improving India’s relations with Israel — including by pressuring the Palestinians to renounce their call for the destruction of Israel and follow the Egyptians in signing a peace agreement. There were also those within India’s intelligentsia and parts of the military who were looking to Israel for the country’s defense interests.

Why did the relationship become so fruitful under the premierships of Modi and Netanyahu, in particular?

Netanyahu and Modi met for the first time in 2014 on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in New York, a few months after Modi became prime minister. Relations between the two countries had already been developing steadily; they had been buying around $1 billion worth of arms per year under India’s previous government. But the difference was that Modi was willing to go public with his relationship with Netanyahu and Israel — despite the negative attention Israel had received a few months earlier as a result of “Operation Protective Edge” in Gaza.

Israel had been waiting for this moment for a long time, and with Modi it finally came. Modi wanted to project himself as a strongman who connected India with a strong and influential country that had “disciplined the Muslims” and was able to defend itself. It was seen as self-reliant, and leading the way when it came to military technology. Modi was elected on a mandate of Hindu nationalism, and Israel’s strong image matched his message.

Netanyahu, meanwhile, was able to present Israel as being close to the so-called largest democracy in the world, and also saw an opportunity to strengthen relations with a state that had historically been one of Israel’s biggest critics and a supporter of Palestinians. So the warming of ties was a massive coup for both leaders. Netanyahu even used photographs with Modi in his re-election campaign a few years later.

The relationship was further strengthened under the Trump administration. India has always been very careful not to upset the Arab world with its foreign policy, so the signing of the Abraham Accords gave Modi cover to strengthen ties with Israel and use the Arab world as justification.

Why is it important to examine the ideologies behind this alliance — namely Zionism and Hindutva? How are these similar, and how do they differ?

At the heart of this new alliance is Islamophobia, and [the fact] that both Zionism and Hindutva are pushing colonial and expansionist ideas. Both are ethnonationalist ideologies with an emphasis on race, territory, and nativism. Judaism and Hinduism are obviously important to Zionism and Hindutva, but the ideologies are not centered around religion. Both see themselves as ancient, age-old civilizations, which is important to building and amplifying their claim of cultural superiority, and both have a particular orientalist disdain for Muslims. Both Zionism (particularly Revisionist Zionism) and Hindutva admired European fascist movements, which had a big influence on [pre-state] Zionist militias and the RSS.

Both Zionism and Hindutva peddle extensively in pinkwashing. When India abrogated Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status in 2019, it embarked on a project of justifying the move by claiming that it would improve the rights of the LGBTQ+ community in Kashmir. This is something Israel has repeatedly pursued to deflect from its own human rights abuses, while presenting its colonialism as a modernizing or civilizing project. Hindutva and Zionism also routinely use feminism to this end, or as a way to demonize Arab or Muslim men.

This is, of course, a colonial tool, which we saw already in the US-led invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq: the promise of delivering women’s rights or democracy to these countries was an essential feature of the invasions. Hindutva borrows from all of this.

Zionism and Hindutva also focus on education and culture, like traditional fascist movements. Both spend a lot of time trying to erase Palestinian, or Indian Muslim or Kashmiri, identity, by adjusting textbooks or appropriating cuisine.

Indian and Israeli leaders both tend to code switch when explaining their goals to different audiences: to international audiences, they speak of terrorism, self-defense, and peace; domestically, meanwhile, they talk about expanding borders, while allowing their surrogates to spout hate speech about Palestinians or Indian Muslims or Kashmiris. It is unsurprising, then, that the TV show Fauda was also a big hit in India. An Indian version set in Indian occupied Kashmir — instead of the occupied territories — is set for release in the coming months.

The rightward lurch in Israel, as well as in diaspora Jewish communities, has had knock-on effects: Kahanism’s popular resurgence, radicalized youth, violent settler attacks in the West Bank, and threats of a ‘second Nakba.’ Are there parallels in India and diaspora Indian communities?

Absolutely. For one thing, there is the question of Kashmir and the concept of Akand Bharat — an undivided India. Just like in Israel, for the Hindu right wing there is no [territorial] boundary. In their imagination, the territory expands from Afghanistan to Myanmar, and anyone inside it who is not Hindu must have come from somewhere else and is therefore a foreigner. Everything evolves from there and, just like in Israel, school syllabuses are changed to reflect this interpretation.

The idea of India [among Indian communities] in the United States or the U.K. is that it is the land of the Hindu people, totally erasing everybody else in that region. Both Zionism and Hindutva are very exclusionary and work toward an ethnocracy where there is only one ethnicity, one idea of the nation, and one language. A settler project derives political and economic advantages through erasure. There are even suggestions that India may be headed toward full-blown apartheid state, too.

In addition to the parallels between Hindu nationalism and Zionism, there are perhaps also parallels in the hesitation some may have in confronting them due to the historical and contemporary racism experienced by Indian and Jewish diaspora communities. How might we overcome this?

There is huge difficulty with raising these issues. On the one hand, when it comes to questioning Zionism, scrutiny or critiques can be quickly dismantled by the accusation of antisemitism. But there are a lot of Jewish voices, especially younger Jews in the United States, that have made a huge effort to try to distinguish between antisemitism and anti-Zionism, and are breaking through. The tide is changing, and people are understanding that it is a farcical argument.

Hindus have not faced the same traumas that Jews have over the centuries, but they are trying to manufacture that trauma using the Jewish experience. Today, the Hindu nationalist lobby in the United States exaggerates the criticism it is facing and reframes it as attacks on Hinduism as such. They call it “Hinduphobia.”

There’s a complicated difference here. Zionism and Judaism, on the one hand, are clearly not the same thing. But some scholars argue that Hinduism and Hindutva are similar in many ways. When you criticize Hindutva, you therefore have to acknowledge that Hinduism itself has a hierarchical caste system too. Some people use this to portray critics as Hinduphobic for targeting a fundamental element of the religion. Others, such as Hindus for Human Rights, say “Yes, there is a caste system in Hinduism, but we are trying to reform it.”

Another issue shielding Hindutva from wider criticism is actually the cultural capital that India has established through yoga, Bollywood, and the symbol of [Mahatma] Gandhi — it’s hard for people to come to terms with the fact that Hindutva comes from the same place as these. The person who killed Gandhi was actually associated with RSS, but at the same time the movement is trying to reclaim him because of the cultural power he wields.

What could be the antidote to this growing extremism?

Hindutva, Zionism, white supremacism, the right wing in Hungary, the right wing in Brazil — these are all connected. People need to see them for what they are: different shades of the same authoritarianism that is expanding across the world and trying to dismantle democracy, using the same means and different myths to capture people’s imaginations.

In India, there has been a major rise in billionaires and inequality has only increased. So the antidote is following the money to see who is actually benefiting from all of this — and that’s where the connections of solidarity are important. If you are able to see who is benefiting from these developments, then you can understand how history and religion are being distorted to control and expand the sphere of influence of the elite.