As liberal Zionism finds itself in the middle of its latest battle for survival, J Street reconsiders forbidden alliances and what it means to be ‘pro-Israel.’

By Soleiman Moustafa

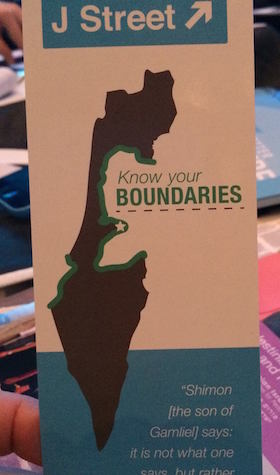

Sitting on every seat in the massive auditorium hosting the opening session of J Street’s 5th annual conference last month was a bookmark emblazoned with the a map and the motto “know your boundaries.” The “pro-Israel, pro-peace” lobbying organization designed a map of Israel with both Palestinian territories partitioned out in green, with Syria’s Golan Heights included in Israel’s boundaries without caveat. Looking up, the auditorium was enveloped in a comforting blue-and-white glow, invoking Israel’s national colors, the American and Israeli flags standing proud at center stage. For an organization ostensibly gathered to push an agenda of Palestinian statehood, any and all symbols of Palestine were conspicuously absent from the impressive display.

The J Street leadership is in the process of testing its own limits, and the demands it has made of its constituency — and of the international community — are rapidly changing. Once-forbidden phrases like “Israeli apartheid,” “resistance to occupation,” and “the Gaza massacre” would make repeated cameos throughout the conference, reflecting a desire to include “the Palestinian narrative” for both strategic and moral purposes. In doing so, however, J Street’s pro-Israel agenda ironically finds itself drifting toward the language and tactics of Palestinian resistance.

The conference occured in the context of an impressive turnout of Arab voters in Israel’s recent parliamentary election, surging the Joint List forward to the third-largest party in the Knesset. This has forced left-wing Zionists to consider how they can “properly” incorporate the Palestinians they once ignored into their political calculations. At a panel hosting a facsimile Knesset debate, one Arab panelist was told to forsake her ties to “extreme” Arab politicians if she wants to work with the mainstream Jewish political parties. This same demand would later be made of Palestine Liberation Organization negotiator Saeb Erekat, referencing the formation of a Palestinian reconciliation government with Hamas.

This struggle between Israeli centrists and Palestinian leftists frequently spilled over to the primarily American audience. Erekat roused repeated standing ovations with impassioned calls for peace at a pulpit that was far more receptive to his “non-violent resistance” than the Labor party. Nabila Espanioly spoke of a civil rights struggle to change Israeli security discourse, well aware that Palestinians now have a critical opportunity to secure their own interests among a left-wing Zionist mainstream.

Reframing Palestinian liberation in Jewish terms

“It’s a very nationalistic thing for me,” Alliance for Middle East Peace director Huda Abuarquob told me after a breakaway session on the danger of Israeli settlements in the West Bank. “I take advantage of every opportunity to spread my message, and consider this my form of resistance,” she said, adding that she had to tailor her message to best reach an audience that might not necessarily agree with her. Activist Samer Makhlouf, meanwhile, suggested to a fairly sympathetic crowd that in light of right-wing political dominance in Israel, J Street should consider moving from a dialectic of “coexistence” into one of “co-resistance.”

The conference was rife with young liberal Jews who have found themselves alienated by their campus Hillels and the policies of the Israeli government; many of the conference’s younger attendees seemed to be grappling with how to reconcile their distaste for racism, disenfranchisement and first-resort violence with the Zionist establishment’s apparent preference for it.

It begs the question of how they can show Israel “tough love” without alienating the country’s supporters. One strategy session began by asking, “can J Street balance the demands of its left and right flanks and continue to build an ever more potent and coherent political force?” To Rabbi David Cooper, this is achieved with what he deemed, “varying modes of non-cooperation” with Israel. J Street cannot safely collaborate with many groups the Jewish community has deemed “anti-Israel,” so Palestinian liberation rhetoric is instead reconstituted on Jewish terms. Resistance becomes non-cooperation, a corrective path prescribed by a concerned and sympathetic family.

Leaders of J Street made repeated affirmations that one of their main goals is to battle against the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement. And yet executive director Jeremy Ben Ami began the conference by recommending that J Street members boycott Israeli economic activity in the West Bank and divest from donors whose money was crossing over the Green Line. Ben Ami’s endorsement of a Palestinian statehood bid in the United Nations also represented a major reversal of the organization’s negotiations-only policy.

J Street remains off-put by ideas that threaten Israel’s demographic “Jewishness,” such as a bi-national state or recognition of the Palestinian right of return. Its reception of the minority of Palestinian voices at the conference ultimately ran parallel with its own vision for a “Jewish and democratic state,” wherein Palestinians may speak freely but cannot be fully invested participants in the collective goals and outcomes of the Jewish majority. It has looked to the Palestinians as an example, but still fears proceeding hand-in-hand with them against Israel’s present course.

Soleiman Moustafa is a graduate student in Near Eastern Studies at New York University. Follow him on Twitter at @soly11111.