Surveillance has always been an integral part of Israel’s strategy to maintain its oppression over Palestinians, whether they are citizens of Israel, occupied subjects, or in exile. Social media, however, has undoubtedly made it much easier for the state to suppress and monitor Palestinian voices and narratives on a global scale.

We saw this play out, almost in real time, during the events in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah this past month: scores of Instagram users, for example, criticized the social media app for suspending accounts and deleting posts and stories regarding the imminent forcible expulsion of families from the neighborhood. Although Instagram later apologized and claimed the removals were a technical error, the recurrence of this phenomenon across online platforms shows that these responses are no accident.

This is not the first time social media companies have been accused of censoring Palestinian dissident voices. In fact, digital surveillance and control of Palestinians has become a foundational strategy for the Israeli government in the information age, with new institutions and policies emerging to carry out these goals.

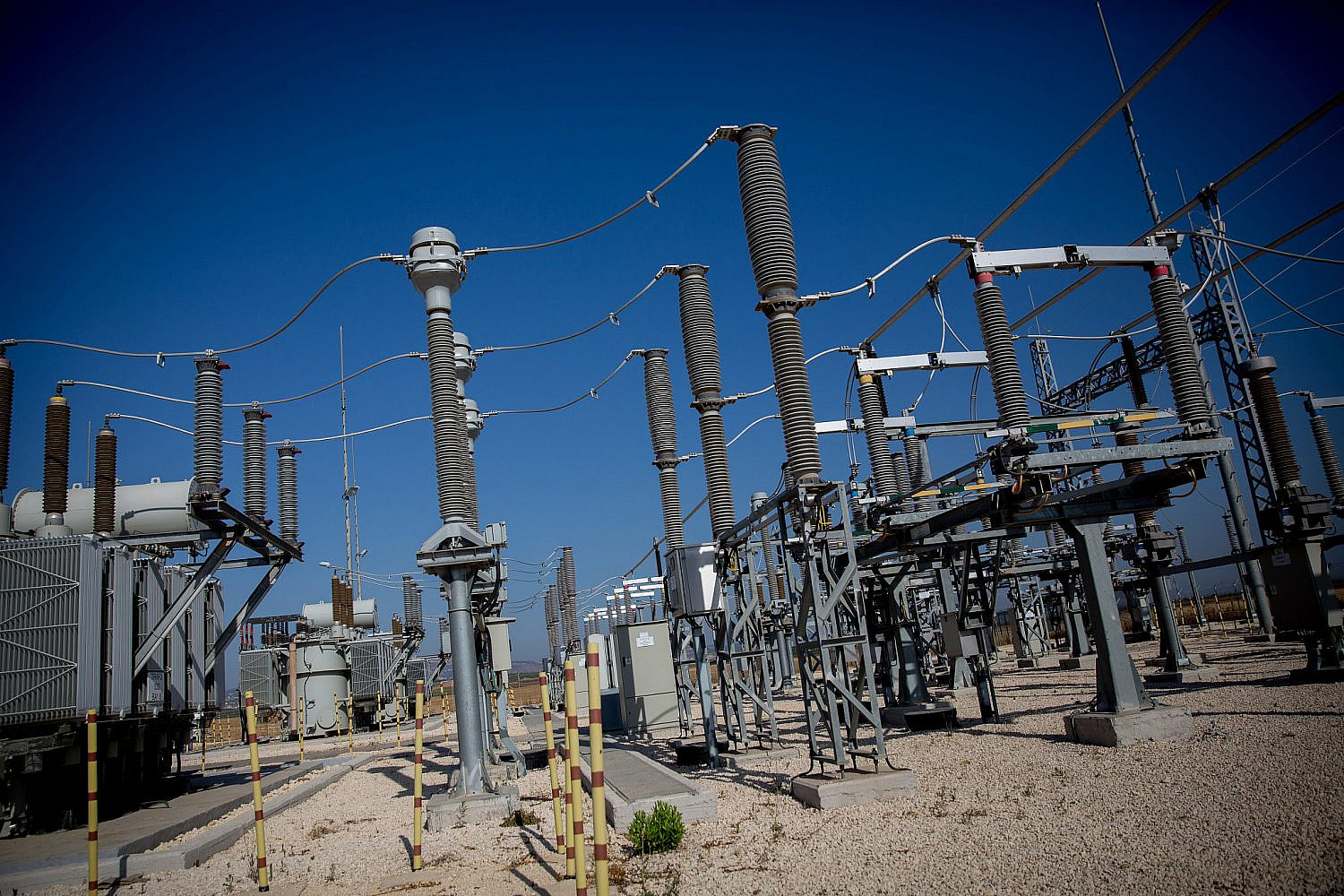

The Oslo Accords, which were ostensibly designed in the 1990s to provide some form of local autonomy in the occupied territories, is supposed to grant Palestinians “the right to build and operate separate and independent communication systems and infrastructures including telecommunication networks, a television network and a radio network.” Yet Israel’s restrictions have systematically hindered the development of any independent Palestinian information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure.

For instance, Palestinian internet traffic relies on a fragmented infrastructure that is entirely dependent on Israeli networks. According to a 2016 World Bank report, in addition to maintaining full control of the core network, Israel frequently blocks the import of ICT equipment to Palestinian-controlled areas of the West Bank. Israel’s control over cyberspace in the occupied territories further hampers service delivery in ways that essentially mirror Israel’s roadblocks, checkpoints, and Kafkaesque permit system in the physical world.

The Israeli army has also routinely jammed and hacked telephone, internet, and broadcast signals among the Palestinian population. It has even destroyed Palestinian network infrastructure in moments when violence is absent; in 2012, for example, the army deliberately and continually cut the sole landline connection between the southern and northern regions of the Gaza Strip, unconnected to any armed escalations.

State-company collaboration

Despite these limitations, access to the internet has given Palestinians a means to transcend their territorial fragmentation and has aided the unification of Palestinian voices. Palestinian civil society has capitalized on the use of social media to circumvent mainstream and traditional media to share their stories of Israeli occupation, displacement, and violence with the world.

But while digital activism may provide a level of virtual mobility, it also makes Palestinians an easy target of state control. Israel has especially intensified its crackdown on Palestinian digital users in the aftermath of the October 2015 uprising, which were sparked after Israeli Knesset members and Jewish settlers stormed the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound under heavy army and police cover, and which became characterized by scores of lone Palestinian knife attacks and Israeli collective punishment.

Since then, Israel has arrested hundreds of Palestinian activists, students, artists, and journalists under the pretext of “incitement” on social media platforms, and has seized private Palestinian communications to pressure them into ending their activism or to blackmail them into collaborating with the state’s security service.

This surveillance is now being done through collaboration between Israeli security units and social media platforms. As a result, Palestinian voices are constantly and disproportionally targeted by companies such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, YouTube, and even Zoom.

Facebook in particular has become a major arena of political confrontation, and is now weighing whether the word “Zionist” should be considered a racist proxy for “Jew” or “Israeli.” Under this policy, reasonable attempts to criticize and hold Israel accountable through constitutionally-protected political speech could be labeled as “hate speech” and removed from the platform. Last week, representatives of Facebook and TikTok even met over Zoom with Israeli Defense Minister Benny Gantz to discuss removing content that allegedly incites to violence or spreads disinformation from their respective sites.

According to a study by the Palestinian digital rights group 7amleh, in 2019, two-thirds of Palestinians said that the fear of censorship had made them worried about expressing their political views on social media. Sada Social, another Palestinian digital rights organization, documented about 1,000 violations against Palestinian social media users in 2019 in the form of removing public pages, accounts, posts, publications, and restrictions of access. 7amleh also reported that in 2020, social media companies complied with 81 percent of Israel’s requests to remove Palestinian online content.

By contrast, it seems to take social media companies much longer to address inciting content posted by Israelis about Palestinians. Last week, 7amleh reported that right-wing Israeli groups have been using Telegram to both incite violence and organize attacks on Palestinians. Despite reports of right-wing extremists in Israel using WhatsApp groups to coordinate violence against Palestinians in Israel, WhatsApp did not offer any systematic solution; it simply removed some accounts of people who participated in some of these groups, only when the accounts were reported.

Persecution and repression

This collaboration to suppress and erase Palestinian voices online effectively extends Israel’s colonial practices from the physical to the digital realm, creating what is being increasingly described as a form of digital colonialism.

Like classic colonialism, digital colonialism is rooted in the tech industry’s design as a system for profit and exploitation. With the cooperation of oppressive governments, big tech corporations use technology to spy on users, process their data, and make decisions about its use. This data applies to speech regulation, content moderation, and freedom of association. As such, social network companies can easily censor content, shape what people see in their news feeds, and determine what kind of activist groups can be created on their platforms.

For Palestinians, physical restrictions and geographical fragmentation leaves access to social media as one of the few tools at their disposal to amplify their voices and counter disinformation about their people and their cause. Silencing them by deleting their posts and sharing their data with the Israeli government has not only led to the arrest of political dissidents; it has turned social media from a tool for strengthening freedom of speech and promoting human rights to one used for persecution and repression.

Governments and other stakeholders have a responsibility to uphold their obligations to protect human rights under international law, including in the digital sphere. This can begin by allowing Palestinians to develop their own ICT infrastructure, while holding social media companies accountable for surveillance of Palestinian activists and demanding they be more transparent about their conduct. With Palestinians being targeted from the streets to their phones, digital rights are an essential front to achieve justice by ensuring that Palestinian voices and stories continue to be heard, documented, and uplifted.