On Oct. 27, the Lebanese and Israeli governments ratified a U.S.-brokered maritime agreement over the Qana and Karish gas fields, located off the shore of the two formally at-war countries.

All three governments have touted the agreement as a groundbreaking achievement, albeit for different reasons. U.S. President Joe Biden praised the deal for “secur[ing] the interests of both Israel and Lebanon,” adding that it “sets the stage for a more stable and prosperous region.”

Deputy Speaker of the Lebanese parliament Elias Bou Saab called the agreement a “new era” for the country’s suffering economy, with Foreign Minister Abdallah Bou Habib expressing “great hope” for Lebanon’s prospects of becoming a gas-producing country. Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid went even further — shortly before the general election that looks to have returned Benjamin Netanyahu to power — claiming “it is not every day that an enemy state recognizes the State of Israel, in a written agreement, in front of the entire international community.”

But as the hype around the deal finally dissipates, the question must now be asked: how much of these varying claims to success are actually true? Notwithstanding the limited benefits to the national interests of both Lebanon and Israel, upon closer inspection, the biggest winners of the agreement are arguably not even the parties directly involved.

Demarcating sovereignty

The territorial dispute originally stemmed from the gas fields’ location within both countries’ respective exclusive economic zones (EEZ), the 330-mile extension beyond any sovereign nation’s maritime borders over whose resources it is entitled to jurisdiction. While the area has been contested since Israel’s establishment in 1948, tensions began to simmer after the discovery of large deposits of natural gas along the Mediterranean coastline in 2010. Lebanon claimed part of the Karish field, but Israel insisted it fell entirely within its waters and was not up for negotiation.

Both governments repeatedly attempted to affirm their claims through the United Nations to no avail. Then, in 2016, Israel unilaterally sold the rights to Karish to the Greek oil company Energean for $150 million, which finalized construction of an extraction terminal earlier this year.

Armed political groups that comprise Lebanon’s splintered political landscape — the most prominent being the Iranian-backed Shi’a party Hezbollah — have continuously lambasted the Lebanese state’s compromising stance on the maritime front, calling it a “red line.” On June 2, three unarmed drones manned by Hezbollah were shot down at the Energean gas terminal, sent to alert workers that it “is not a safe area.”

Brokered by Amos Hochstein, the U.S. Department of State’s energy envoy, the maritime agreement sees Israel retain rights to the Karish gas field, allowing Energean to continue operating the terminal.

Lebanon, in turn, has affirmed rights to the untapped Qana gas field, set to be explored and developed in 2023 by French gas company TotalEnergy in coordination with the Lebanese government. However, the agreement stipulates that while technically under Lebanon’s sovereignty, Israel is entitled to receive 17 percent of TotalEnergy’s profits from the gas field as its southern tip falls within the newly demarcated boundary.

Another step toward normalization

While the Lebanese government is optimistic that the maritime deal will breathe new life into the country’s crippled economy, the commercial viability of the Qana gas field is yet to be known. In 2020, Lebanon conducted a search for gas deposits in an area overlapping with the field but “found no commercially-viable amount of gas to develop.”

Following the results of the fruitless search, a 2021 report from the non-profit Natural Resource Governance Institute warned that Lebanon “should not stake its economic or energy future on oil and gas.” While the TotalEnergy survey may yield different results, the report added that even if deposits were to be found, “there is no cause to think that oil and gas exports would be an economic ‘turning point’ or a solution to the current miseries,” detailing how “becoming a producer could make some of the country’s economic governance problems worse.” Even in the best-case scenario, it would not be until 2030 that TotalEnergy is able to construct a terminal and begin to extract Lebanese gas — years the country cannot afford in its current moment of crisis with need for immediate solutions.

Despite two years of aggressive brinkmanship over both the gas fields, Hezbollah, in a surprising change of stance, greenlit the deal during the final weeks of negotiations. Hezbollah was likely pressured by the sheer degree of the ever-escalating economic crisis, in a year that saw the party and its bloc lose a parliamentary majority following the Lebanese elections in May.

For Israel, in comparison, not much will change economically from the deal. Jurisdiction over the much more fruitful Karish gas field was long taken as a given prior to the agreement, with Energean’s construction of a gas terminal beginning in 2017 and an export agreement already signed with the EU earlier this summer.

What Israel has gained, though, is security. First, security for its economic developments along the Mediterranean coast by affirming sovereignty over Karish, where any attack — from Hezbollah or otherwise — would be tantamount to an invasion with all its repercussions.

Second, geopolitical security to deepen the regional trend of diplomatic normalization with Israel, which in turn is facilitating mutual, American-led strategic, economic, and military agreements against Iranian influence — a trend epitomized by the 2020 Abraham Accords and further fueled in part by American anxieties over China. And while Lebanon insists that the maritime deal does not represent either an end to formal hostilities or the diplomatic recognition of the Israeli state, the mere cooperation on defining such permanent territorial boundaries is arguably a watershed moment.

The big winners

Perhaps the biggest winners of the agreement, though, are actors based far away from the Mediterranean coastline: the Biden administration, the European Union, and the American and European gas companies contracted to operate the gas fields.

With the world suffering from rampant inflation in 2022 in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent sanctions on Russian oil and gas, the United States and EU have turned to Mediterranean gas and Gulf oil as alternative tools to bring down global market prices. This also comes after U.S. oil and gas companies refused to increase domestic production following Russia’s invasion, hoping to take advantage of the crisis to offset minor dips in profit margins during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Earlier this year, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen signaled the EU’s intent to shift the continent’s dependency on Russian energy to the Israeli-led East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), comprised of Egypt, Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, and Jordan. “The Kremlin’s behavior only strengthens our resolve to break free of our dependence on Russian fossil fuels,” Von der Leyen said while visiting Israel in June. “We are now exploring ways to step up our energy cooperation with Israel.”

In lieu of this, Egypt, Israel, and the EU signed a joint memorandum of understanding on June 15 to boost gas exports to Europe and meet the gap created by sanctions. The Greek Energean and French TotalEnergy, in addition to Italian gas company Eni operating in Egypt, are set to hugely benefit from this increased European import of gas through the EMGF, with the EU incentivizing its gas companies to further invest in an Israeli market that has mostly been dominated by American companies.

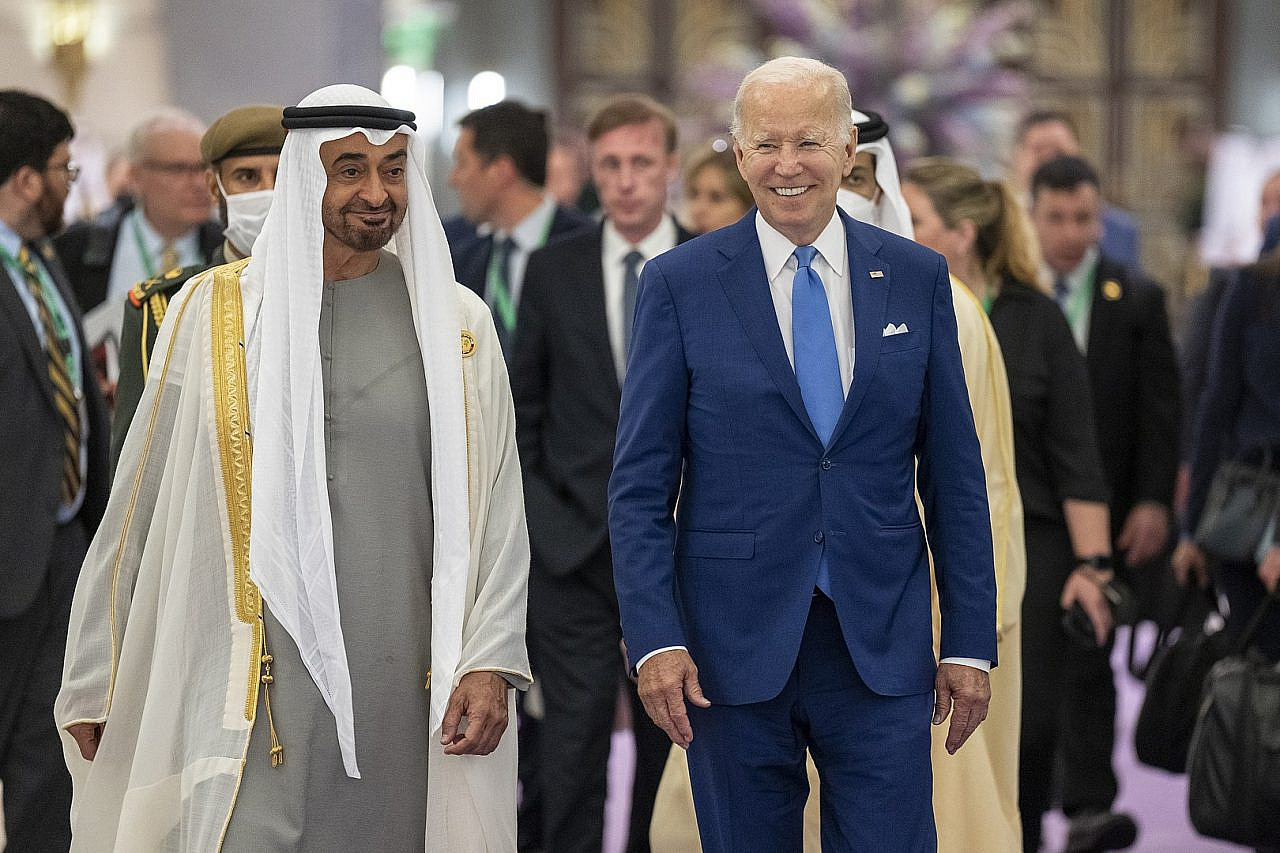

At the same time that the EU began brokering energy deals with Israel and the EMGF over the summer, President Biden similarly sought out Saudi Arabia’s support in responding to the oil and gas crisis when he visited the world’s largest oil exporter in June — immediately after meeting governmental officials in Israel.

Biden had previously vowed during his election campaign to make the kingdom a “pariah” due to Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman’s direct order to murder Saudi-American journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018, as well his overseeing of the war in Yemen. This tension led Saudi Arabia and its ally the United Arab Emirates to deny Biden’s request in March for increased oil exports after the Ukraine invasion.

Meeting privately with bin Salman and attending the Jeddah Security and Development Summit, Biden backtracked on his criticism of the murder of Khashoggi and brokered deals between the kingdom and the American defense firms Boeing and Raytheon. Biden and his envoy were able to triumphantly return to Washington with an informal Saudi pledge to have the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC+) commit to “increas[ing] supply over the course of July and August.”

In the past few weeks, however, Saudi Arabia and Gulf Arab states have chosen to spurn the Biden administration by voting in favor of the OPEC+ decision to cut oil production. Announced on Oct. 5, OPEC+ cited an unforeseen surplus created by inflation-induced lower demand, bringing profitability margins down, as informing its decision. Washington has since accused Saudi Arabia of colluding with Russia, an OPEC+ member, in pushing the measure through.

The OPEC+ decision came ahead of the U.S. midterm elections this past week. Biden’s tenure has been markedly defined by the fluctuating price of oil and gas in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and in the wake of Russia’s Ukraine invasion, and he has been struggling with low domestic approval ratings.

However, the administration has seen an uptick in approval in recent months, in part after managing to stabilize domestic oil prices, both by tapping into the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve and gaining bin Salman’s pledge. The skyrocketing of domestic fuel prices once more, however, threatened this upswing in Biden’s approval ratings ahead of the midterm elections.

Given this volatile context on multiple fronts, it is not a coincidence that the Biden administration has now chosen to swoop in and swiftly broker a settlement over untouched gas fields that have been hotly contested for the last 10, if not 80, years. As a result of the U.S. intervention, Energean even optimistically began gas production in Karish before the deal was even finalized.

It is therefore ironic that the American private sector that initially sent Biden on his goose chase for oil and gas throughout 2022 is now set to benefit the most from the increased export of Israeli and Mediterranean gas, with energy corporation Chevron, for example, owning a majority stake in Israel’s two largest gas fields, Leviathan and Tamar.

Long term dangers

While the Israeli-Lebanese maritime agreement is a victory for U.S. and EU interests in the short term, the disparate way in which the two leading international powers have turned to Mediterranean oil and gas is telling of their hastening global decline.

For the past three decades, with the Soviet Union no longer presenting a challenge to U.S. hegemony on the global stage, both the United States and the EU have gambled the security and stability of their economies in favor of unchecked growth and profits through deregulatory, neoliberal economic policy. Since the 1980s, domestic American and European energy production and manufacturing operations have been steadily shuttered in favor of importing non-renewable energy sources and exporting manufacturing to countries with weak labor and environmental laws — particularly China — in a bid to maximize speculative financial growth.

Now, the consequences of such near-sighted economic policy have come to bite them politically. Their dependence on Russian and Saudi oil is exposed, and China’s economic influence is overturning the “First World’s” hegemony over global markets and international relations.

Rather than reflect on the unsustainability of their policies, Washington and Brussels are instead forcibly attempting to wrangle the global political and economic landscape back in re-alignment with their interests, even if it fuels growing polarization. Recent geopolitical trends in the Middle East, with the Israel-Lebanon agreement being the latest, reflect this: forcing through unpopular diplomatic normalization with Israel in an effort to retain economic interests disrupted by Russia; escalating militarism against Iran; and antagonistically countering Chinese investments in the region with no sound economic reasoning beyond political spite.

There can be no winners in this growing polarization between U.S.- and EU-aligned states on one hand, and the self-described anti-imperialists in Iran and its proxies backed by Russia and China on the other. The postcolonial conflicts that have marked Middle Eastern geopolitics throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries — of which the Israel-Lebanon maritime dispute is one small feature — seem set to only escalate in different forms.