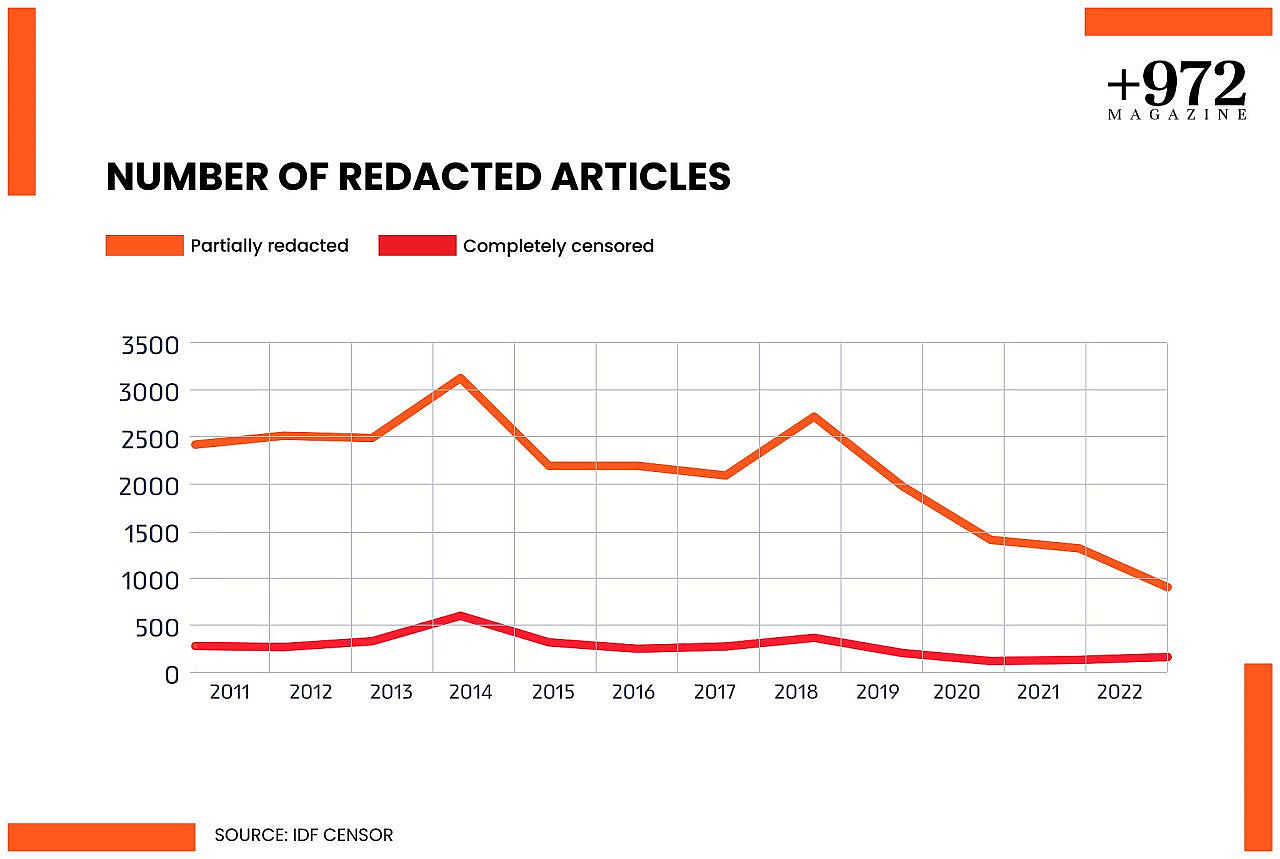

Last year, the Israeli military censor blocked the publication of 159 articles across various Israeli media outlets, and censored parts of a further 990. In all, the military prevented information from being made public an average of three times a day — on top of the chilling effect that the very existence of censorship imposes on independent journalism that seeks to uncover government failings. The censorship data was provided by the military censor in response to a freedom of information inquiry submitted by +972 Magazine and the Movement for Freedom of Information in Israel.

The rate of interventions by Israel’s military censor declined in 2022 for the fourth year in a row, and was at the lowest level since +972 began collecting data on the censor’s activities in 2011. Last decade saw a minimum of 2,358 interventions per year in media reports by the censor, and usually far more than that; the figure for 2022 is “only” 1,149 censored pieces — a 20 percent decrease from 2021.

According to Or Sadan, an attorney with the Movement for Freedom of Information in Israel, the mere existence of this censorship causes a chilling effect, which is a major reason for this year’s decrease. Another potential factor is the change in personnel at the top of the censorship unit: Ariella Ben Avraham, who was the chief censor during its peak years — and who now works at NSO Group — left the role in 2022, and the position is now held by Kobi Mandelblit.

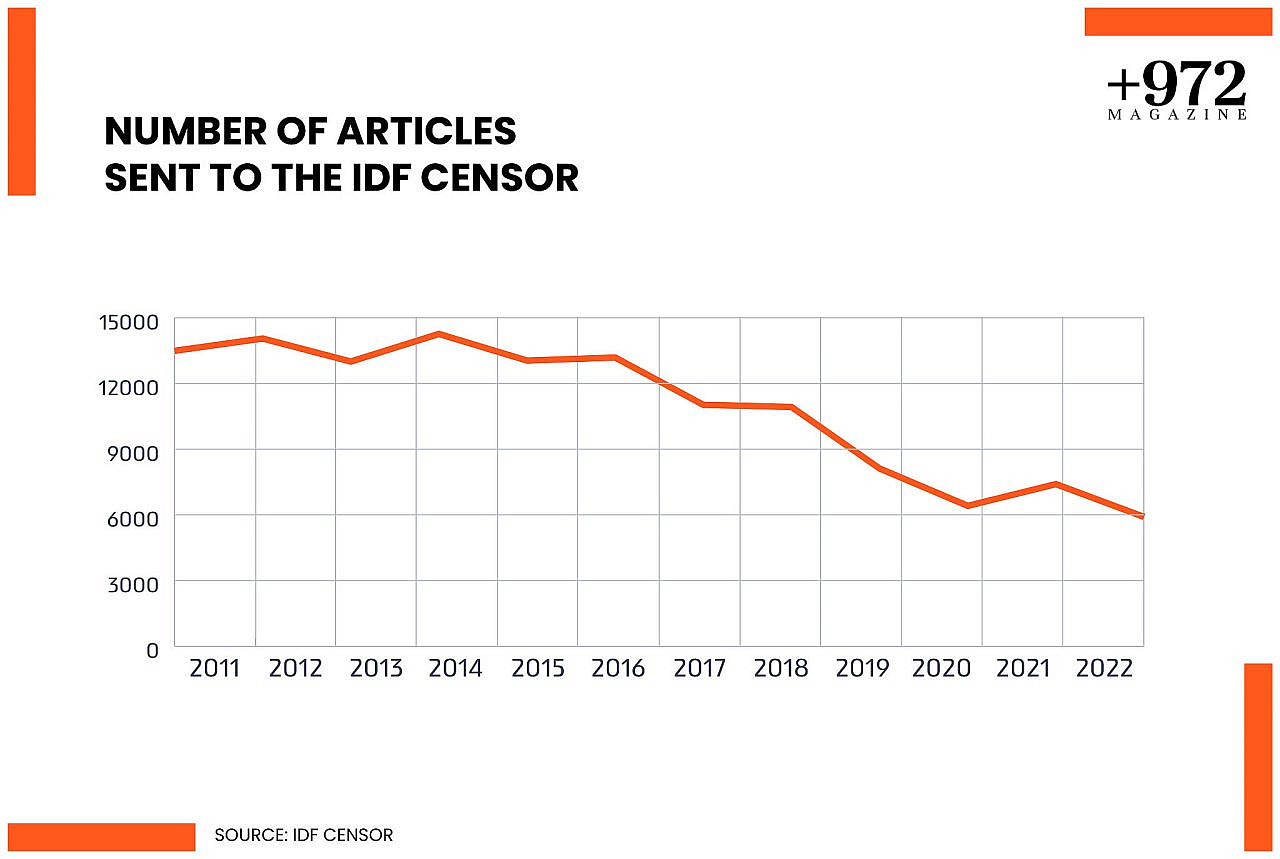

There has also been a considerable drop in the number of articles media outlets have submitted to the censor for review. In the last decade, outlets submitted between 11–14,000 articles each year, whereas last year that figure stood at 5,916. This decline can perhaps be explained by decreased interest in sensitive security affairs, or as a response to the reduced intervention by the censor and the decline in the banning of articles for publication.

Israeli law compels journalists to submit any article to the military censor if it discusses security issues — which, comprising six densely-filled pages of sub-topics, is very broadly defined. Media outlets grapple daily over what to send to the military censor, a decision ultimately made by the editors. For more background on the censor and +972’s stance toward it, you can read the letter we published to our readers in 2016.

The censor can also proactively take down information that has already been published in the news or on social media, and Ben Avraham even tried to compel prominent bloggers and writers online who were not journalists to send her texts before publication. However, in contrast to previous years, the military censor this year rejected our request to categorize its statistics in order to clarify where it censored texts submitted to it, and where it intervened to take down information that had already been published.

The censor did not provide other statistics we requested, including a breakdown of its activities by month, by its reasons for intervening, or by the media outlets involved. We also did not receive figures on how many items in the Israel State Archives — which was not originally under the purview of the censor — were either removed from public access or redacted. The censor would only confirm that 2,670 files from the archives were submitted to it last year, and that “the vast majority” were published without redaction — which reveals little about the censor’s activities vis-à-vis the archives.

Despite the reported decrease in the statistics the censor did share, the very existence of the military censor remains an extreme deviation from basic democratic norms. Israel is the only country that purports to belong to the circle of Western democracies that exercises such aggressive censorship against journalists, effectively deterring writers from addressing issues that are vital to the lives of citizens.

“The public must be aware that there are pieces of information that journalists want them to know, but that are blocked by the censor,” Sadan said. In pursuit of this end, Sadan, the Movement for Freedom of Information in Israel, and +972 have been working together to “raise public awareness of the number of incidents in which the public’s right to know has been violated,” Sadan continued. In so doing, he added, requests for information on the censor’s activities “allow for long-term follow-up, which reduces the fear of the misuse of this authority.”

Even as the military censor continues to violate press freedom, its activities have become increasingly redundant — even absurd — in an era when anyone can post information online and achieve widespread circulation, or access information published elsewhere in the world as a means of bypassing censorship. Thus, for example, were Israeli news outlets initially barred from revealing that a former Mossad agent, Erez Shimoni, was one of those killed in a boat incident in Italy last May — news that made headlines around the world. Eventually, as has happened in other such cases, reality overwhelmed the security establishment, forcing it to relent and allow the Israeli press to discuss what had already become common knowledge around the world.

Israel fell 11 spots in this year’s World Press Freedom Index, compiled by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), dropping from 86th place (out of 180) in 2022 to 97th place in 2023. The military censor’s activities are cited in RSF’s fact file on Israel, and the policies and proposals of the new government are given as the reason for its lower ranking this year.

Most read on +972

At a recent Knesset committee hearing on military censorship, Anat Saragusti, the Press Freedom Director at the Union of Journalists in Israel, noted Israel’s position in the index, while citing +972’s ongoing reporting, and pointing out that the use of gag orders in Israel — issued unilaterally by judges with the input of the security establishment, without representation for the journalists — is on the rise. This trend, Saragusti added, is causing a significant increase in the number of issues that the press is prohibited from addressing.

Even as the work of the military censor continues, however, it does not intervene in the publication of articles on army and settler activity in the occupied territories; on the government’s creation and maintenance of two separate legal systems for Jews and Palestinians in the West Bank; on the repression of legitimate Palestinian protest; on criminal cases arising from the army’s killing of Palestinians, which are usually not investigated; on the imprisonment and shooting of Palestinian journalists, our colleagues; and so on. Most mainstream outlets do not report on these issues, or else cover them in a biased and distorted manner — not because of government restrictions, but because of self-censorship.

This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.