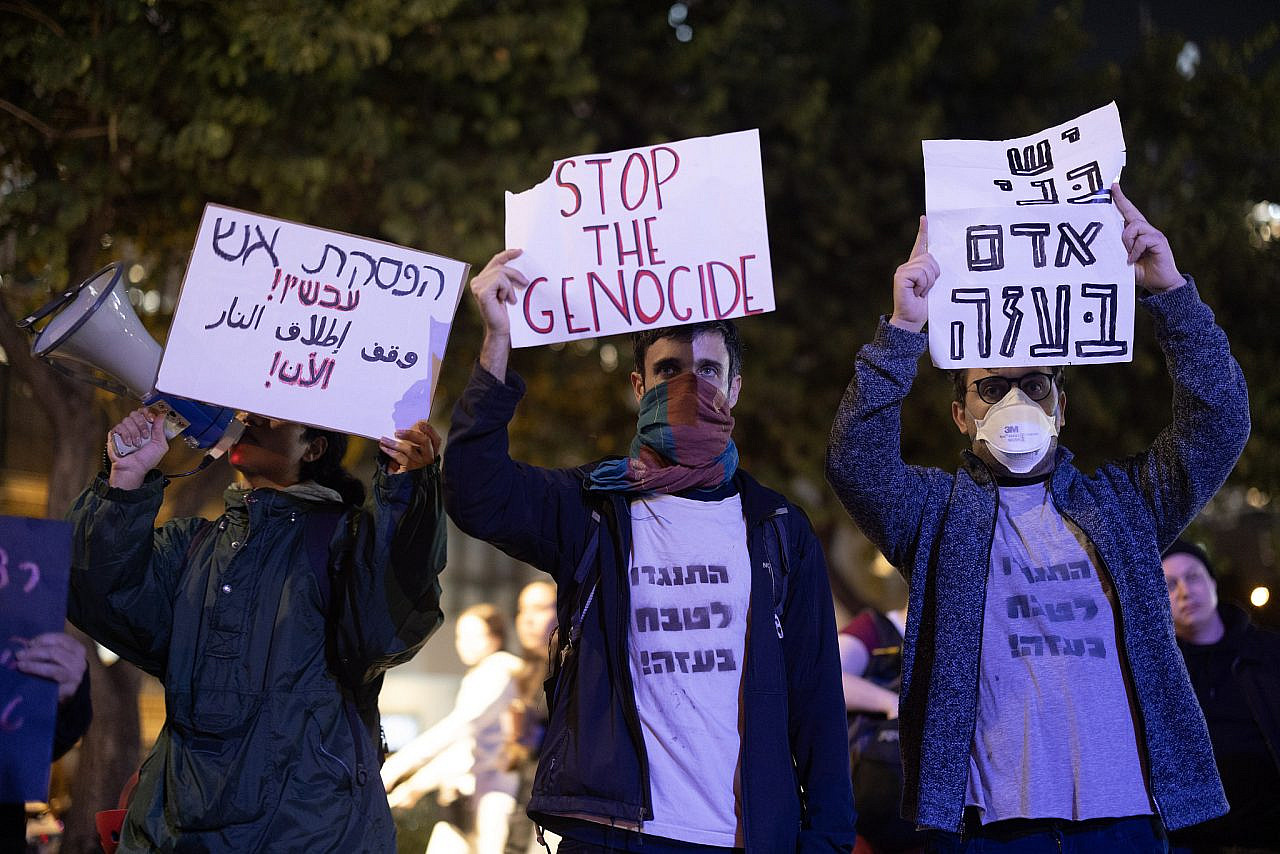

On the evening of Jan. 16, several dozen activists gathered in front of the Kirya in Tel Aviv, home to Israel’s Defense Ministry and army headquarters. It was one of the first Jewish-Israeli demonstrations explicitly condemning the military’s assault on the Gaza Strip since the war began, and the police acted swiftly to suppress it: dozens of officers were deployed in advance, and they refused to allow the protest to take place in its intended location. They confiscated signs reading “Stop the massacre” on the grounds that these offended public sentiment. One activist was arrested, and several others were assaulted by police.

This sequence of events is far from exceptional. Since October 7, Israel’s police have been implementing a consistent policy of preventing or limiting any protest against the war — in contrast to protests in solidarity with the hostages and their families, which have been permitted in certain areas. This policy is still in effect despite Israel’s Supreme Court issuing an interim injunction earlier this month prohibiting National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir from interfering with the policing of demonstrations; in large part, police appear nonetheless to be enforcing the minister’s desired crackdown on freedom of expression during the war.

Anti-war activists across the country — Palestinian citizens as well as Jews — who were interviewed for this article all mentioned one word: “fear.” Even veteran political activists say they have never been so fearful of protesting. They are afraid of being arrested, which for Palestinian citizens could spell months in prison. More than ever, they said, it is dangerous to show solidarity with the people of Gaza, and they feel that politicians’ belligerent rhetoric is directly impacting police behavior.

“From the early days of the war, it was clear that this was the policy,” Maysana Mourani, an attorney with the Haifa-based human rights and legal center Adalah, told +972 and Local Call. “The police have taken on new powers to immediately repress protests, even when a protest permit isn’t required, because of their supposed ‘lack of manpower.’”

Adalah has petitioned the Supreme Court several times since October 7 to challenge such police bans on the right to protest. Despite the Court’s intervention earlier this month, however, it has repeatedly failed to intervene on numerous other occasions, meaning the police have had broad discretion to decide which protests to permit. “It depends on the identity of the demonstrators and the slogans,” Mourani said.

“The courts see danger in every act of protest,” she continued. “People are automatically thrown into detention for a few days, and pretty quickly it turns into an indictment and a decision to keep them detained until the end of the proceedings. It’s completely deranged; this is a new standard.”

“The rule is that the police suppress any protest,” Amjad Shbita, the national secretary of the leftist Hadash party, told +972. On Jan. 9, Hadash attempted to organize a protest in the northern town of Kabul; given that the attendance would have been fewer than 50 people, there was no requirement to obtain a permit. Regardless, the protest was over before it even began: “The police detained the secretary of the local Hadash branch and threatened him, so we gave up. The branch canceled the protest.”

Some of the strictures appear to have relaxed slightly in the past few weeks. In Arraba, another Arab town in the north, an anti-war rally of approximately 150 people took place on Jan. 12, making it the largest Palestinian-led rally inside Israel since the start of the war.

Last weekend, larger demonstrations in Haifa and Tel Aviv — which the police had originally prohibited on the grounds that they didn’t have the manpower to secure them — were allowed to take place following petitions to the Supreme Court. Over 1,000 people took part in the Tel Aviv rally, which was organized by the Jewish-Arab movement Standing Together, while police capped the Hadash-led rally in Haifa at 700.

Nonetheless, there is a feeling among the interviewees that these are changes around the margins. “The police let up a bit,” Shbita said, “but you still feel their iron fist.”

‘They are trying to intimidate us’

Suppressing protests, both during war and otherwise, is hardly new for Israel’s police. But the current attack on freedom of expression is being carried out with unprecedented speed and force.

A week after the war began, Police Commissioner Kobi Shabtai announced a ban on demonstrations in solidarity with Palestinians in Gaza. “Anyone who wants to identify with Gaza is welcome to,” he said in a video posted to Israel Police’s Arabic social media pages; “I’ll put him on the buses that are heading there now.”

Police Spokesperson Eli Levy echoed this sentiment soon after, telling IDF Radio: “Anyone who even dares ask permission to hold a demonstration in support of Gaza or the Nazi terror organization that committed a Holocaust here — of course we will not allow it. Whoever holds demonstrations without permission — we will come and deal with the demonstration with all the tools [we have].” He added: “Anyone who dares to go out and say one word in praise of Gaza will be behind bars.”

On Nov. 7, the Supreme Court rejected Adalah’s petition against the police’s decision not to grant a protest permit to Palestinians in the cities of Umm al-Fahm and Sakhnin on the grounds of a “manpower shortage.” The Court did say, however, that “a sweeping and general prohibition banning demonstrations in advance because of their content is not within the authority of the police commissioner,” and insisted that every permit request is given due consideration. Yet despite these guidelines, all but one protest organized independently by Palestinian citizens of Israel since October 7 have been prohibited.

Rula Daood, a Palestinian citizen of Israel and the national co-director of Standing Together, which organized the largest demonstration against the war so far last week in Tel Aviv, explained the extraordinarily difficulties of trying to organize protests in the current climate. “The police gave us a permit, but then they retracted it. At first, they said the march was approved, but the location was not suitable and speeches were banned. Things kept changing.

“Before that, they said that there could be no march, only standing, and no speakers,” Daood continued. “We wanted thousands of people to march in Tel Aviv calling for an end to the war, a ceasefire agreement, and the return of the hostages. We want to strengthen that voice and talk about the day after.”

The police rationale for the prohibitions — that they lack sufficient manpower to secure the protest from counter-protesters — seems to have been unfounded. None of these rallies have generated significant counter-protests, save for a few passersby shouting curses at those protesting.

“They are trying to intimidate us: to create a feeling that the police are sovereign, that they do what they want, and that no one can do anything to them,” Daood said. “It’s political policing, and it’s very scary. When you’re a Palestinian citizen, the fear more than doubles. People are even afraid to attend small rallies, to appear in photographs, to write anything.”

On Nov. 9, the High Follow-Up Committee — an umbrella organization representing Palestinian citizens of Israel — planned to hold a peaceful protest in Nazareth, with the participation of a limited number of invitees. But the police carried out preventive arrests — including former Knesset member Mohammad Barakeh, the Committee’s chairman — effectively banning the protest from taking place.

After his arrest, Barakeh petitioned his case to the Supreme Court, but the justices rejected it. The following day, the commander of the Nazareth police station, Eyal Kihati, sent Barakeh a message, warning him against holding the protest: “As stated, the message is clear and unequivocal. We will not tolerate violations of judicial decisions or local decisions of mine as station commander, and any organizing by you or representatives of the High Follow-Up Committee will be met with zero tolerance and in accordance with the tools that the law gives us.”

In December, Barakeh was trailed by police vehicles. The protest was ultimately permitted to take place later that month, without further arrests.

‘There is a sense of helplessness’

On Oct. 19, an anti-war demonstration was held in Umm al-Fahm. The fierce police pushback — the demonstration was dispersed with stun grenades, clubs, and sponge bullets, and the police arrested 12 of the protesters — made it a symbol of police repression since the start of the war.

The police requested that 11 of the detainees, including four minors, be remanded in custody, and the Magistrate’s Court approved the request without a hearing for the detainees because Shabbat had already begun. After a hearing on Saturday night, nine of the detainees were released on conditions, and two others — Ahmad Khalifa and Muhammad Jabarin, whom the police considered the organizers of the protest — remained in detention.

The pair were indicted for shouting political slogans that the Court deemed to constitute incitement, and their detention was extended through the end of the proceedings — possibly the first time this has happened purely on the grounds of slogans. Mourani, the attorney with Adalah, represents Jabarin. “They claim it’s about incitement and slogans and not about the demonstration, but you can’t separate one from the other,” she said.

“This is a change of policy,” Mourani continued. “When we discussed an alternative to detention, they argued that house arrest and remote monitoring were impossible because [the detainees] would theoretically be able to violate it and leave the house to demonstrate. So, it really is about the demonstrations, ultimately. It’s political persecution. These are not new slogans, and it’s not anything specific to October 7.”

Theirs is not a singular case. Since October 7, the State Prosecutor’s Office has encouraged investigators in dozens of cases to ask the court to extend detention until the end of proceedings, including cases centered on “incitement” on social media.

In one of the hearings, Khalifa — one of the pair who were indicted — described the conditions at Megiddo Prison, where he is being held as a security detainee, to a judge: “People are being held in handcuffs … They are being dragged around as if they were animals. If you lift your head, you get hit on the head. I saw it on a daily basis. If one of the guards catches someone smiling, they take him away; there’s an area there with a ‘blind spot’ [out of view of security cameras] that the whole prison knows about.”

Khalifa also testified that a detainee in the cell next to his was beaten and later died of his wounds, echoing testimonies that +972 reported on last month.

According to Shbita, people are afraid to protest because of stories like these that they hear from those who were arrested. “Political activists have said to themselves in the past, ‘We’ll be detained for a day or two, it’s not the end of the world,’” he said. “But now there’s a feeling that this is the end of the world, even among people who are regulars at protests, because of the physical violence during the detentions.”

While small protests in Arab localities in the north have taken place in recent weeks, there have been no such demonstrations in the Naqab/Negev in the south. “It pains me that all over the world people are demonstrating for us — in Europe people are out in their hundreds of thousands — but that here we are unable to demonstrate for ourselves,” said Huda Abu Obeid, a political activist from the Naqab. “There is a sense of helplessness. The only thing we could do before the war was protest, and now we can’t even do that.”

According to Abu Obeid, there were initially no protests because people were so taken aback by the events of October 7. “It was a real shock,” she said. “We are used to Israel attacking, but this was the first time that the Palestinians are the ones attacking in such a massive way. We didn’t know how to react.”

Abu Obeid also links the lack of protests to the chilling effect caused by the mass arrest campaign against Palestinian citizens of Israel in the wake of the “Unity Intifada” of May 2021. “The Shin Bet succeeded in frightening everyone,” she said. “They summoned activists [for interrogations], they intimidated them, they came to places of political activity. The feeling is that no matter what you do, even if it’s not related to demonstrations, you’ll always be persecuted.”

‘We are silenced from all directions’

In the absence of larger protests, most anti-war activity has consisted of small, local vigils for which permits are not required — but even these have been attacked by the police and passersby. The vigils tend not to be advertised publicly on social media, but rather in closed groups. In order to avoid the formation of a right-wing counterprotest, they usually last less than an hour, and activists arrive and leave together fearing that they will be attacked on the way.

The latest such action to be forcibly dispersed by police was a small gathering last week in the Arab town of Al-Batuf, near Nazareth. Earlier in the month, activists in Tel Aviv held a street exhibition of recent photographs from Gaza; passersby, some of them armed, attacked the activists and ripped the pictures away while the police watched on.

While the international and local Arabic media have shown great interest in these protests and vigils, the events are almost completely ignored by mainstream Israeli outlets. “Our voice is barely heard in Israel,” said Michal Sapir, an activist with the “radical bloc,” which organized the street exhibition. “We are silenced from all directions. The state is not showing what is happening in Gaza, so it’s important for us to stand up and say that the killing of civilians in Gaza that is being done in our name must end, and that there is no military solution.”

When the war began, the activists had to figure out how to circumvent the ban on demonstrations. “We did it gradually,” Sapir said. “We didn’t know what the reaction would be. At first, we just joined the families of the hostages. We tried to see if it was possible to stand there with signs calling for a ceasefire, and we saw that we could. Slowly, we switched to more radical slogans and marches from HaBima [a large public square in downtown Tel Aviv]. We noticed what could be said, and what would be met with [police] violence.

“Until the crackdown on the signs [at the Jan. 16 protest outside the Kirya], the police didn’t really bother us, but now they have a new policy,” Sapir continued. “They’re tired of us being near the military headquarters.”

From time to time, Sapir added, the activists are attacked by passersby. “A delivery man threw eggs at us. But there is usually tolerance, and sometimes support.”

Activists in Jerusalem have held several small demonstrations against the war in recent weeks, including some in front of the U.S. Consulate. One of those, a vigil for those killed in Gaza which took place in early January, was forcibly dispersed by police, with two demonstrators arrested and photographs of those killed in Gaza confiscated. Last week, another protest vigil in Jerusalem was attacked by police, who confiscated signs and pushed demonstrators away.

“Everything is scary,” an activist with the left-wing group Free Jerusalem, who preferred not to be named, told +972 and Local Call. “The stakes are higher. Unlike in the past, when we would advertise events openly, now we are more careful. Public opinion and statements by Israel’s entire political leadership have shifted to the right, and this has raised the level of fear and anxiety.”

According to him, at one of the first demonstrations calling for the release of the hostages, Free Jerusalem activists called to end the war in order to ensure their release, and were attacked by passersby. “It wasn’t even directly against the war, but there was violence,” he said.

“In the two demonstrations we held on consecutive Saturday nights [Jan. 6 and Jan. 13], the police violently dispersed us after only a few minutes and didn’t allow us to protest,” he continued. “They took our big signs that said ‘No to war in Gaza’ and ‘Ceasefire now.'”

‘Police swore at us, called us sluts, and told us to go back to Gaza’

In Haifa, activists have come up with creative ways to evade the police’s aggressive repression of anti-war activity in the city. On Dec. 28, a small group of activists held what they called a “jumping” demonstration, in which they moved from place to place before the police could stop them.

“We didn’t publicize it in large [social media] groups, because we know police officers are monitoring those,” said Gaia Dan, a Haifa-based activist. “It actually worked pretty well. We stood in the German Colony [in downtown Haifa] for 20 minutes, and by the time the police arrived, we were already at another point. There the police arrived within five minutes, so we fled to the third point. We’re trying to be present without it leading to violence.”

Dan had been arrested at another protest in the city held one month earlier, where activists stood silently with tape over their mouths to protest the political persecution against those expressing dissent against the war. “When we arrived, there were already three police cars there, and within moments, the district commander shouted through a megaphone that if we didn’t disperse in two minutes, they would disperse us by force.”

According to Dan, police then pounced on the protest. “They arrested one protester and began tearing up signs and pushing people everywhere. They tore down my sign, which was very tame: ‘Stop the silencing.’ I was dragged and kicked. That’s how I was arrested.”

Inside the police car with two more detainees, Dan said the police officers “swore at us, called us sluts, told us to go back to Gaza, and asked how we weren’t ashamed to demonstrate like this in wartime. While we waited at the station, the policemen continued to curse, and sang songs about returning to Gush Katif [the bloc of Jewish settlements in Gaza that were dismantled in 2005] and destroying Gaza. After three hours, we were released without conditions.”

The police’s crackdown on dissent in Haifa came immediately after the outbreak of war. On Oct. 18, the Hirak movement planned to hold a demonstration in the city; hours before it was due to start, the police issued a statement saying no permit had been granted and that they “will not allow any show of support or solidarity with the Hamas terrorist organization” and “will act with a firm hand in accordance with the law to disperse the demonstration, including using mass dispersal measures as necessary.”

The activists went ahead with the demonstration regardless; dozens of police officers came and declared it illegal, violently dispersing the protesters and arresting five activists who refused to leave. Adalah, whose lawyers represented three of the detainees, was told that the detainees would remain in detention all night on orders from the police commissioner. The next day, the Haifa Magistrate’s Court ordered their release.

On Oct. 29, activist Yoav Bar was arrested at his home with what police called “incitement materials” — which turned out to be political posters — before being released without conditions.

Since the arrests at the Dec. 28 protest, Dan believes people in Haifa have been afraid to go out to the streets. “At the first demonstration, there were 20 of us; now it’s hard to get five,” she said. “People also see what’s happening in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem — they don’t want to come to a demonstration and get beaten, and I understand them. It’s hard and exhausting, every time you arrive thinking it might end in arrest or being squashed onto the pavement. I’m scared too. But at the end of the day, we are privileged as Jews to know that we usually won’t face prolonged detention, and it’s important to demonstrate however we can.”

Shbita, the Hadash secretary, hopes that now, three months into the war, the Jewish mainstream will also understand why they are protesting. “The shock on October 7 was real, but I think as time goes on people are asking questions,” he said. “Sadly, people in Israel only start asking the tough questions when their own side is harmed. They don’t care about the 20-30,000 Palestinian victims but the danger to the lives of the hostages, the soldiers killed, the diplomatic problems, the economic crisis — all these elements will cause the public to ask questions.”

+972 and Local Call contacted Israel Police for comment on their policy of preventing protests against the war, what authority they have to confiscate signs, and the treatment of detainees in Haifa by police officers.

In response, a police spokesperson stated: “Without referring to one case or another, we note that Israel Police operates in accordance with the provisions of the law and the conditions set by the Attorney General’s directive. Israel Police will allow the legitimate right to express the freedom of protest, but will not allow manifestations of violence against police officers engaged in security and maintaining public order and will not allow disturbances of public order of any kind.”

A version of this article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.