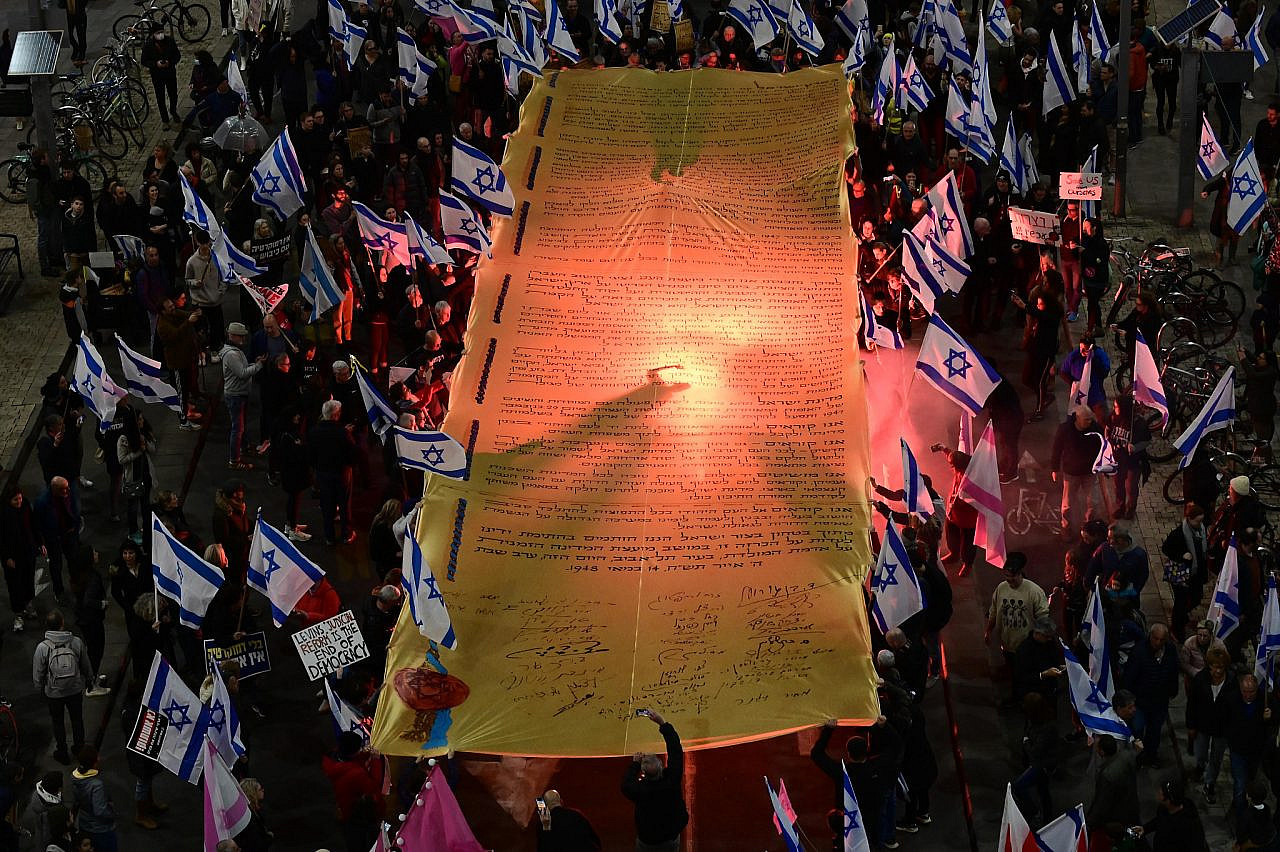

The protesters taking to the streets against the Israeli government’s judicial overhaul have recently latched onto “the values of the Declaration of Independence” as an expression of the democracy they wish to preserve. In this vein, opposition politicians such as Yair Lapid and Moshe Ya’alon proposed enshrining the text of the Declaration in Israel’s Basic Laws, to serve as “a common ethos and a common good” for everyone; the Tel Aviv Museum of Art announced its commitment to the values of the Declaration, as did the Israeli Opera and Reichman University; and there is a new protest movement calling itself “Loyalists of the Declaration of Independence,” which, in February, brought a giant Declaration of Independence to Tel Aviv’s Kaplan Street — the site of the massive anti-government protests of recent weeks. Yuval Noah Harari even suggested that “families [in Israel] … read Israel’s Declaration of Independence” at their Passover Seder.

These references to the Declaration almost invariably cite one of its most famous lines: that the State of Israel will guarantee “complete equality of social and political rights to all its citizens irrespective of religion, race or sex.” But are these efforts to celebrate and reclaim the Declaration a viable recipe for democracy?

To answer this question, I want to propose a historical analogy. Like all analogies, it isn’t perfect, but I think it can help inspire critical thinking that will give us pause the next time we hear people uphold Israel’s Declaration of Independence as an embodiment of the state’s democratic nature.

Let’s imagine that, in today’s Russia, a broad protest movement suddenly breaks out against President Vladimir Putin — enraged by his brutal dictatorship, his imprisoning of political opponents, his enabling of violence against women, his frequent attacks on LGBTQ people, and the blood spilled by his war in Ukraine. And let’s imagine that this imaginary protest movement is united around a real-life document: the Soviet constitution of 1936.

The Soviet leader Joseph Stalin personally helped draft this constitution and boasted that it was the most democratic in the world. It is, indeed, highly progressive: Article 112 guarantees that judges will be independent and loyal only to the law; Article 122 enshrines the equal rights of women in all realms of life — economic, social, and political; Article 125 promotes important values like freedom of expression, freedom of the press, and freedom of protest and assembly; and according to Article 127, an arrest can only be made with a court order.

When the Soviet constitution was first ratified, many Western intellectuals were convinced by Stalin’s propaganda, among them the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw and the French writer Romain Rolland, both of whom won the Nobel Prize in Literature. But if our imaginary popular movement spoke only of the text of the constitution and the values it held, and not of what actually happened in the Soviet Union during those years, the movement would be justifiably accused of denying crimes against humanity. Stalin, as we know, murdered millions of people during the 1930s; was responsible for confiscating food from Ukrainian farmers thus causing a famine; conducted show trials; and began ethnic cleansing operations across the Soviet Union, forcibly relocating minorities from their homes to the furthest corners of the country.

The Israeli Declaration of Independence was proclaimed on May 14, 1948. At the time, most of the residents of what had until then been the British Mandate of Palestine were Arabs, but the supposedly democratic Declaration did not dwell on the nature of this demography. Instead, it opens with 12 paragraphs, each expounding on the connection between the Jewish people and the Land of Israel, completely erasing the non-Jewish majority in the land.

Paragraph 13 includes the famous sentence declaring equality for all citizens, and Paragraph 14 calls on the UN to welcome Israel into the family of nations. Only in Paragraph 15 do “Arab inhabitants of the State of Israel” suddenly appear out of nowhere, being called on to “preserve peace and participate in the upbuilding of the State on the basis of full and equal citizenship and due representation in all its provisional and permanent institutions.”

It is no coincidence that Arabs and their rights are mentioned alongside Israel’s request to be admitted into the UN. The Declaration of Independence refers to the Partition Plan of 1947 as the basis for international recognition of the right of the Jewish people to statehood. According to that proposal, the UN required the future Jewish state (and the planned Arab state) to ratify a constitution that would guarantee “to all persons equal and non-discriminatory rights in civil, political, economic and religious matters and the enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms, including freedom of religion, language, speech and publication, education, assembly and association.”

Israel’s admission into the UN was not preordained, as a number of Arab countries were already members of the organization, and their opposition to Israel’s establishment could have derailed its application for UN membership. Indeed, Israel’s efforts to join were twice rejected by the UN — in May and December of 1948 — and it was ultimately accepted only in May 1949. The Declaration’s guarantee of equal rights was intended first and foremost to shore up Western diplomatic support for Israel.

Just as it would be ridiculous to talk about the rights guaranteed to Soviet citizens by Stalin’s constitution without also talking about the reality of the Soviet Union’s practices at the time, so too must we dig into the lived reality of the “Arab inhabitants of the State of Israel” around the time of Israel’s Declaration of Independence. About a month before Israel declared independence, the Haganah (the paramilitary group that would eventually become the core of the Israeli army) began to implement Plan Dalet, under which Palestinian cities and towns — including those outside the borders of the Partition Plan — were occupied and emptied of the majority of their inhabitants. At the end of April 1948, nine villages in the Jaffa district were occupied and cleansed of their Palestinian residents in what was called “Operation Hametz” — referring to types of food that Jews must traditionally scour from their homes during Passover — while Palestinian localities in the eastern Galilee were destroyed in “Operation Matateh [Broom]” at the start of May.

These and other expulsions were accompanied by massacres and the indiscriminate shelling of densely populated areas. All in all, as the historian Rosemarie Esber points out in “Under the Cover of War: The Zionist Expulsion of the Palestinians,” around 400,000 Palestinians — over half of all the refugees to ultimately emerge from the Nakba — were evicted from their homes prior to Israel’s independence. Instead of receiving the “full and equal citizenship” supposedly guaranteed to them by the Declaration, these Palestinians were left with nothing, on the other side of the border. The Palestinians who managed to stay within Israel’s borders endured expropriation and looting of most of their property, forced ghettoization, and many other discriminatory practices

Most Israelis are much more familiar with the ideals of the Declaration of Independence than they are with what happened to Palestinians around the time of Israel’s founding. Reading the Declaration of Independence at the Passover Seder, then, would be a choice of ignorance: perpetuating the erasure of Palestinian existence under Israel’s control, as occurred symbolically in most of the Declaration and physically through the military operations during the Nakba.

I have an alternative suggestion: instead of perpetuating this tradition of ignorance and reveling in the imaginary generosity of the Declaration, why not read a Palestinian text at the Seder, in honor of Passover, the holiday of liberation? Among the many options you could choose, I recommend the wonderful poem by Mahmoud Darwish, “The Eternity of the Cactus,” from the book “Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone” — about the journey of a father and son into exile, and their dream of returning.

A version of this article was originally published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.