On September 20, 1966, David Ramin, then Israel’s representative at the UN, presented his country’s official position on Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, to the General Assembly. Israel, Ramin said, condemned Ian Smith’s unilateral declaration of independence in November 1965, which led to the colony of Southern Rhodesia’s secession from Britain and the establishment of a dictatorial regime run by a white minority that discriminated against and oppressed its African majority.

Israel condemned Smith’s use of state of emergency, censorship, and administrative detentions, which deepened discrimination and repression in the country. Furthermore, Ramin said, Israel regretted the lack of concrete steps to promote democracy that would guarantee basic rights and equality for all the inhabitants of Rhodesia, expressed full support for the UN Security Council’s decision to impose a boycott and embargo — both military and civilian — on the country, and supported the call to refrain from any activity that would legitimize and encourage Smith’s regime.

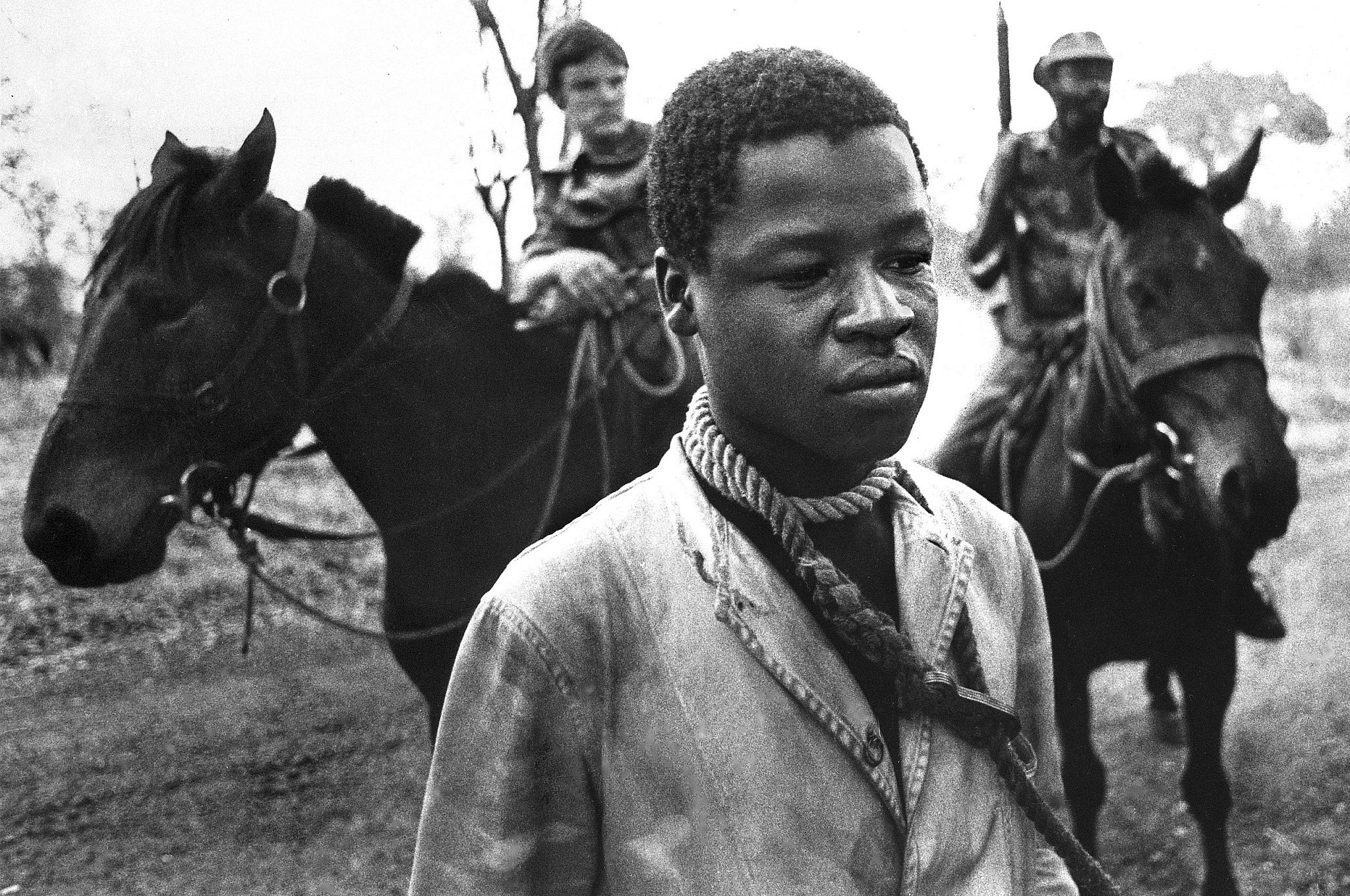

Ramin told the General Assembly that Israel believes in the right to equality of all human beings in all areas of life, that it rejects all doctrines and forms of racial discrimination, that it affirms the right to independence and self-determination of every people, and that it opposes the denial of the social and political rights to four million Rhodesian-born Africans. It was those principles that undergirded Israel’s refused to recognize Smith’s regime and announced that it would immediately take all necessary measures to prohibit relations with the regime — particularly economic relations.

Ramin concluded his speech with a moral statement par excellence:

Over 90 percent of humanity now lives in sovereign states. The human race is becoming increasingly aware of the right of all human beings to freedom and equality. Discrimination is increasingly condemned by decent people. The United Nations can be proud of his contribution to this astonishing change. The ending of any remnants of oppression and discrimination is one of the most urgent conditions for bringing peace and global stability, and therefore it is the goal of this organization to continue its steps towards its realization.

How is it possible that an Israeli representative took a just, legal, political and moral position — even going so far as to support a boycott of Rhodesia — in the UN General Assembly? This sounds surprising, since about six months after Ramin’s remarks — and until this very day — Israeli governments have reacted quite differently to UN Security Council and General Assembly resolutions condemning the its occupation of the Palestinian territories.

Thanking Israel

Until 1967, Israel was considered a symbol of the victory of justice and anti-colonial struggle among many circles in the Third World. The newly-independent African states welcomed military and civilian assistance from Israel and supported the Jewish state at the UN. Israel, in turn, condemned apartheid, racism, and discrimination.

Foreign Ministry documents from Israel’s State Archives reveal that in the mid-1960s, Israel formed an unusual connection with Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), the African liberation movement in Rhodesia, which was established in 1963 after it split from the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU). ZANU later came under the leadership of Robert Mugabe, who would lead Zimbabwe after the fall of the white regime for nearly four decades.

According to a series of telegrams from the Israeli Foreign Ministry headquarters in Jerusalem and the Israeli missions in the United Kingdom, Zambia, Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa, Israel provided monthly financial grants to ZANU, helped finance the movement’s expenses in London, and even funded its travel and flight expenses as part of a campaign designed to persuade the world to recognize the urgency of the struggle in Rhodesia. ZANU officials visited Israel on a regular basis and did not hesitate to contact Israeli representatives with requests to increase financial assistance. According to a telegram dated June 8, 1966, a ZANU representative in London asked the Israeli embassy to help finance furniture for his apartment, as well as to purchase alcoholic beverages for a party thrown for Rhodesian students.

In their meetings with Israeli representatives, ZANU representatives shared vital information about their political and military plans, the support they received from the newly independent African countries, and even made sure to update the Israelis on the internal disputes of the liberation movements inside Rhodesia. On March 27, 1964, Israeli Ambassador to Malawi Gideon Shochat sent a telegram about his meeting with the then ZANU leader, Ndabaningi Sithole, who, “stressed how much he appreciated the aid from Israel and his confidence that it would continue in the future, especially in human training. He praised the help provided through the embassy in Dar [Dar-Al-Salam, the capital of Tanzania], emphasizing that his appreciation is not only for the help provided but for how it is provided.”

Israel unsuccessfully tried to renew its ties with the rival ZAPU movement, which had been severed in 1963 (“So as not to bet all the money on one horse!” Shochat wrote in another telegram dated March 5, 1964). ZAPU was supported by Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt and repeatedly condemned Israel. Israel’s support for ZANU stemmed from the outset from competition between Israel and Nasser for regional influence across the African continent. Israel estimated that ZAPU fighters had also received military training in Arab countries. Shaul Tuval, who served as chief assistant to the Africa Department at the Foreign Ministry, wrote in a telegram dated March 12, 1964: “According to the information we have, Nkomo, who heads the PCC (ZAPU), receives support from Cairo for anti-Israel propaganda.”

‘Terrorism is the main way’

Did Israel provide the rebels against white rule with military training or weapons? The documents show that dozens of ZANU activists received various training courses in Israel, the nature of which is difficult to ascertain, since documents belonging to the Defense Ministry, the IDF, the Mossad and the Shin Bet are still classified.

What is clear, however, is that some Israeli representatives believed that the economic boycott was not enough; they compiled documents and reports stating that the way to bring about change would be through armed struggle. Tuval wrote in a November 10, 1966 report:

“The only way left for the Africans in Rhodesia — at this stage — is to hasten the date of the takeover by a majority of Africans… To this end, liberation movements must intensify acts of violence in Rhodesia, with the assistance of the OAU (Organization of African Unity) and outside the OAU. This is in order to train the resilience and tolerance of the African masses to the Rhodesian authorities; increase the number of those joining the ranks of underground fighters; sow insecurity in the hearts of whites and motivate them to flee Rhodesia and encourage the moderates among them to seek understanding with the Africans, while putting pressure on the authorities to do so. This requires brave, enduring African leadership that will prepare the public for the seven-year struggle. It seems to me that the national chairman of ZANU is putting his party on this path slowly, but with a resolute decision.”

In a telegram dated February 2, 1965 that concluded a meeting between Tuval and ZANU’s secretary for pan-African affairs, Tuval noted that there were dangers to the armed struggle and that, “The end of such an intervention could be the victory of African nationalism and majority rule. Or the victory of European nationalism and a seven-year or longer war against the rule of the minority.”

In a telegram dated May 3, 1965, Tuval stated that the armed struggle of the liberation movements was intensifying, raising fears that in the absence of an alternative, those movements would fall into the hands of China and the Arab states. He concluded, “These chances must be considered against the background of our relations with Britain and on the basis of the question of whether we should do more than we are doing.”

Israel’s ambassador to Zambia, Ben Zion Tahan, also expressed support for the armed struggle. In a telegram sent on November 23, 1965, he wrote: “In my opinion, terrorism is the main way, although it is the most difficult for the fighters.”

In a summary prepared by Tuval on July 24, 1964 regarding Mugabe’s visit to Israel, he quotes the Zimbabwean leader saying: “What they have in the movement today is thanks to the support of Israel.” According to Tuval, Mugabe also said, “We want to train our people in guerrilla warfare and that requires training camps, equipment and money.” It is not clear if all of these were indeed provided eventually.

In a telegram dated August 19, 1964, the first Secretary of the Israeli Embassy in Tanzania Yohanan Bein wrote about his meeting with the Mossad representative and the deputy secretary general of ZANU, in which, “they were not given any hope of undergoing the requested training in Israel.”

Bein and the Mossad representative clarified at the meeting that they would not interfere in the internal dispute between the liberation movements, yet in another telegram from November 1964, Bein wrote that he had met with a ZANU representative who had updated that approval had been obtained for combat training in Zambia. Bein gave him money to travel to Zambia and informed the Israeli Embassy in Lusaka that a ZANU representative would meet with them there.

According to a telegram sent by Foreign Ministry spokesman Moshe (last name is unknown) on June 25, 1965: “Rhodesia’s liberation movements are unable to obtain what they want with the underpowered weapons… Granting Mugabe what he wants now will allow his men to use the knowledge they acquire here against their opponents. We have no interest in that.”

The documents also reveal that unconfirmed rumors were circulating in Rhodesia at the time, especially among the Jewish community, that Israelis were training military operatives from the liberation movements in Zambia.

The very existence of an internal Israeli debate on the question of direct support for the armed struggle in Rhodesia-Zimbabwe is particularly interesting in light of Israel’s position on Palestinian liberation movements, both before the 1967 war and after it. Israel has turned membership in Palestinian movements into a security offense and has persecuted and eliminated their activists, including those who have not directly participated in armed struggle.

Breaking the boycott

Israel’s situation changed after the 1967 war and the beginning of the occupation, with large sections of global public opinion began to see Israel as a colonial regime. At that time, Arab countries began pouring money into Africa. After the 1973 war, many non-aligned countries, and almost all the African states, severed official diplomatic ties with Israel. Israel’s close connection with liberation movements, such as those in Rhodesia, became impossible.

Israel apparently continued to maintain ties with ZANU for some time, and in 1968 ZAPU also tried to renew ties with the Israeli government. Lou Kedar, from the Africa Department of the Foreign Ministry, wrote in a telegram dated December 15, 1968:

We are happy to renew our relationship with ZAPU. Because it is ‘good for the Jews,’ we are willing to do so to be good to the Rhodesians. We are aware of their difficult situation in all respects and it is clear to us that the modest assistance we can offer them will help them put their affairs in order and will not promote the release of Rhodesia.

But ties had severely cooled. In a telegram from A. Toledo from the Africa Department to the Israeli Embassy in London on May 20, 1969, he asked to delay the visit of the deputy secretary general of the ZAPU to Israel: “The cooperation and assistance to the liberation movements is currently under discussion in principle and comprehensively. In this context, we will also discuss possible visits by members of the liberation movements and we will inform you.”

The Israeli boycott of Rhodesia, which began in December 1965, was not limited to the import and export of goods. Israel banned Israeli banks from transferring funds to and from Rhodesia, did not recognize the validity of passports issued by the Smith regime, and refused to allow Rhodesians not associated with the liberation movement to enter its territory.

From the outset, there was never a consensus among the Israeli establishment to support the boycott, and after the 1967 war, attempts to sidestep sanctions increased. While the Foreign Ministry supported the boycott, Israeli companies and the Ministries of Finance and Industry, respectively, violated it and secretly purchased Rhodesian goods at cheap prices. Ships with corn, asbestos, and sugar — and possibly also copper, steel, and tobacco — arrived in Israel, bypassing UN Security Council resolutions. Israeli authorities also looked into possibility of purchasing meat from Rhodesia.

Because Rhodesia relied on the export of minerals and agricultural produce, and the low cost of goods was based on employing African workers under conditions of exploitation and coercion, trade was a central factor propping up Smith’s regime. One of the reasons the Finance Ministry circumvented the boycott was that Rhodesia banned taking money out of the country, and the Rhodesian government stipulated that it would only transfer funds raised by the small Rhodesian Jewish community for Israel on Israel’s importing of Rhodesian goods.

After the United Kingdom complained to the UN about Israel’s boycott violations, the government tried to cover it up by using fake documents showing the goods were produced in Mozambique, South Africa, and Malawi. The Israel Bureau of Statistics caused an embarrassment after publishing details in English of Israeli exports to Rhodesia in 1969. This is what the Israeli Ambassador to Mali, Meir Shamir, wrote in a telegram sent on March 5, 1970: “We are submitting an official document of the State of Israel about our trade with Rhodesia, Mozambique, Angola and more. To facilitate the work of our enemies, everything is beautifully translated into English.”

Another embarrassing incident occurred when Rhodesian published an advertisement for leather jackets made in Israel. Dr. Y. Shachar, who led the Industry Ministry’s department that dealt with trade with developing countries, responded to the gaffe in a telegram from February 11, 1969: “We assume that these things reached Rhodesia through another country and we have no possibility of monitoring it — after all this is not a weapon.”

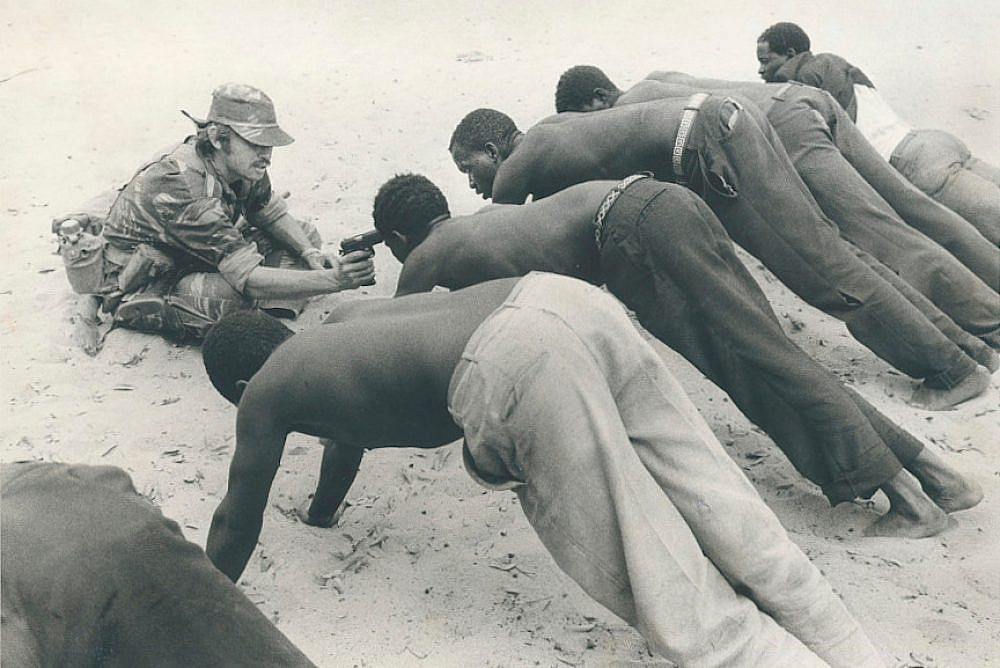

It is unclear whether Israel also sold weapons to the Smith regime. According to several reports, Israel sold American helicopters, which were used to fight the liberation movements, to Smith in 1978 via intermediaries. Rhodesian security forces also used Uzi rifles, and from 1977 even produced a local model of the Uzi, called the Rhuzi, which included original parts of the Israeli submachine gun.

The wrong side of history

Israeli aid to the liberation movement against the white regime in Rhodesia was not motivated by altruism. Israel was then on a journey to win hearts and minds in the newly independent African countries, including support for civilian projects across the continent. In a telegram sent from the Israeli embassy in London on October 21, 1965, it was proposed that the Israeli president send a letter of support for the struggle for majority rule in Rhodesia, and that, “By identifying with the African elements already at this stage it will be easier for our future efforts to withstand Arab and communist defamation when the matter gets increasingly complicated.”

Before the 1967 war, Israeli policy around the world, and in Africa in particular, was complicated. While it supported the liberation movement in Rhodesia, in the mid-60s the Israeli government also supported the murderous and corrupt regime of Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire, aided the rise of Idi Amin in Uganda, and began building close security and diplomatic ties with the apartheid regime in South Africa. Still, at that time, Israel had the opportunity to be on the “right side” of history.

However, from the moment Israel occupied the Palestinian territories, its honeymoon with African countries came to an end, and the potential for partnership with liberation movements and with global struggles for freedom and equality was greatly diminished. The new mantra of the State of Israel became: “Do not interfere in our internal affairs and we will not interfere in yours.”

Meanwhile, the regime in Rhodesia fell and became Zimbabwe. Robert Mugabe, who seized power in 1980, went from being a hero of the liberation movement to a cruel dictator who ruled the country for 37 years. Mugabe, who came to Israel in the early 1960s to request weapons and training, received 30 crowd control vehicles from Israel in the early 2000s that were used to disperse demonstrations and help oppress his people.

The position of the State of Israel — as read aloud by David Ramin in 1966 at the UN General Assembly — on the importance of freedom, equality, the independence of nations, and the use of boycott sounds like science fiction today.

Translated from Hebrew by Ofer Neiman.

This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.