A 2012 viral social media campaign brought Israelis and Iranians together when it seemed like the region was on the brink. With the threat of war looming again, +972 Magazine speaks to Ronny Edry, one of the founders of the ‘Israel Loves Iran’ campaign.

In 2012, Israel and Iran looked to be on the brink of war. Prime Minister Netanyahu told an audience at AIPAC in March of that year, in what became known as his “nuclear duck” speech, that “all options” were on the table to stop Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. Foreign policy analysts, along with regular Israeli and Iranian citizens, fretted that Israel would carry out a preemptive strike against Iran’s nuclear program, sparking a regional war.

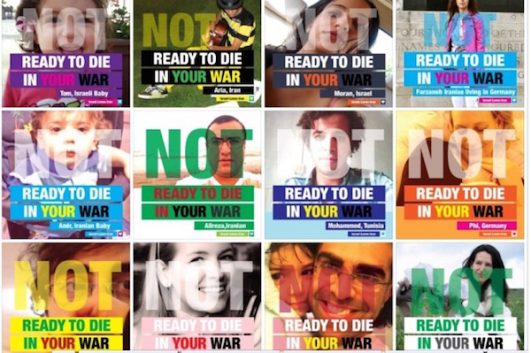

The threat of a looming war led Ronny Edry and Michal Tamir, two Israeli graphic designers, to launch a Facebook campaign called “Israel loves Iran,” which quickly went viral. Israelis posted pictures of themselves, and sometimes their families and friends, with the text: “Iranians, We will never bomb your country, We love you.”

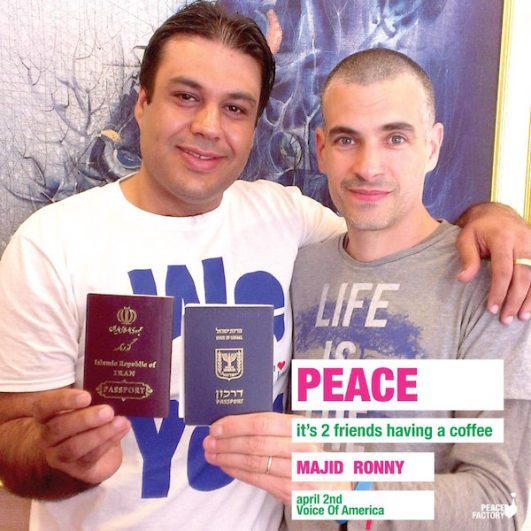

In response, an “Iran Loves Israel” Facebook page cropped up, then similar pages like “Israel Loves Palestine” and Palestine Loves Israel.” The campaign eventually coalesced into an umbrella initiative called Peace Factory, run by Edry and Tamir, which put the “Israel Loves Iran” campaign posters on 70 buses in the Tel Aviv Area.

As the threat of war between Israel and Iran looms over the region once again, +972 Magazine spoke to Ronny Edry by phone on Friday.

“The idea then was really to connect to the Iranian people,” Edry explained. “In 2012, very few people [in Israel] had Iranian friends on Facebook, if at all.”

From that perspective, the campaign succeeded. “I, and a lot of my friends, have a lot of Iranian friends now,” he said. “We developed deeper connections. I travelled abroad and met them.”

The current situation today is even scarier, he continued. “Today it looks like the war has basically started.”

What made the 2012 campaign successful, Edry reflected, was that it gave people a sense that they were not alone in dealing with a frightening situation; it gave them a way to do something positive about it.

“People were able to see that we’re not so different from each other, that most people don’t want war,” Edry said. “And from there tons of connections developed.”

That simple success, however, may be the most difficult to recreate, “making people believe that maybe there’s someone, say, in Gaza or Teheran, that they can talk to, that not everyone there is crazy.”

Since 2012, the role of social media in politics — and people’s relationship to social media in general — has changed dramatically. If 2012 was a time of great hope in the power of social media to bring people together, in 2018, those hopes have largely been dashed.

The photos and graphics from the 2012 campaign convey an earnestness and optimism about what social media could achieve that seems out of place in an era of “fake news” and bitter online political polarization.

“I don’t know if the campaign we did in 2012 would be the same in today’s world. Then it was new, it was surprising, it was fresh, it was very not cynical,” Edry said. “Today everything seems a bit like fake news, everything seems to have a political agenda, and people have grown tired of that. It’s less interesting, it’s less believable.”

And yet despite the cynicism that currently pervades social media, people — Israelis and Iranians alike — have begun to seek out the “Israel Loves Iran” and “Iran Loves Israel” Facebook pages again.

“We started posting pictures from 2012 with a call for people to send new pictures, and we’ve already received a ton,” Edry added. “[There are] a lot of Iranians who want to join up again and say the same things. People have sent pictures, they’re asking us about it, posting on Facebook, sending messages.”

“The crazier the situation gets, the more people seek out some kind of sanity,” Edry concluded. “And they try to find these kinds of pages.”